You've probably seen photos of the Sahara or maybe the Gobi. They look like what we imagine a desert should be—rolling sand dunes and the occasional camel. But the Dasht e Kavir desert Iran is different. It’s weird. Honestly, it's more of a salt-crusted wasteland than a sandbox. Imagine a place where the ground has literally curdled into sharp, jagged salt crusts that can snap a boot sole. That’s the Great Salt Desert.

Most people think of deserts as lifeless. Static.

This place moves.

Beneath that blinding white surface, there are actual mudflats and marshes that can swallow a vehicle if the driver isn't careful. It’s located right in the middle of the Iranian Plateau, spanning about 77,000 square kilometers. That is roughly the size of the Czech Republic, just to give you some scale. It’s a massive, salty void that defines the geography of central Iran, separating the lush forests of the north from the arid plains of the south.

The Science of Why It’s So Salty

Why is it like this?

📖 Related: Luxury Hotels Boston MA: Why the Old Classics Still Beat the New Glitz

Basically, millions of years ago, this whole area was covered by a salt-rich ocean. As the Tethys Ocean retreated and the earth buckled to form the mountains we see today, the water got trapped. It evaporated. What was left behind was a concentrated layer of minerals and salt. Because there’s almost no rain—seriously, we’re talking maybe 3 centimeters a year—the salt never washes away. It just sits there, baking under a sun that regularly pushes temperatures above 50°C.

Geologists like those who have studied the area’s "salt domes" (diapirs) find this place fascinating because the salt actually flows like a liquid over vast periods. It’s not a rock; it’s a slow-moving, geological glacier made of sodium chloride.

If you’re standing in the middle of it, the silence is heavy. It's the kind of quiet that makes your ears ring. You start to realize that the "Kavir" isn't just a place; it’s a barrier. Historically, the Silk Road traders had to skirt around the edges because crossing the center was essentially a death sentence. One wrong turn into a salt marsh and you were done.

Rig-e Jenn: The Dunes of the Spirits

There is one part of the Dasht e Kavir desert Iran that locals used to avoid at all costs. It’s called Rig-e Jenn. The name literally translates to "Dune of the Genies."

For centuries, travelers swore they heard voices in the wind. They believed spirits lived there, lureing unsuspecting caravans to their doom in the quicksand-like salt mud. Science has a slightly less supernatural explanation: the "voices" are actually the sound of sand grains rubbing together or the wind whistling through the cracked salt crusts. But when you’re out there alone and the sun starts to set, the supernatural explanation feels a lot more plausible.

- The Salt Crusts: These aren't smooth. They look like frozen waves or cauliflower.

- The Wind: It’s constant and carries a fine silt that gets into everything.

- The Temperature Swing: You’ll bake at noon and shiver at midnight.

- The Isolation: You can drive for hours without seeing a single shrub.

Sven Hedin, the famous Swedish explorer, was one of the first Westerners to really document the interior of the Kavir in the early 20th century. His accounts are harrowing. He talked about the psychological toll of the horizon never changing. It’s a literal hall of mirrors made of salt and heat mirages.

Where Life Actually Happens

You’d think nothing could live there. Wrong.

On the fringes, life hangs on by its fingernails. The Asiatic Cheetah—one of the rarest cats on Earth—occasionally roams the outskirts near the Kavir National Park. There are fewer than 50 of them left in the wild. They hunt Jebeer gazelles and wild sheep that have adapted to drinking water so salty it would make a human sick.

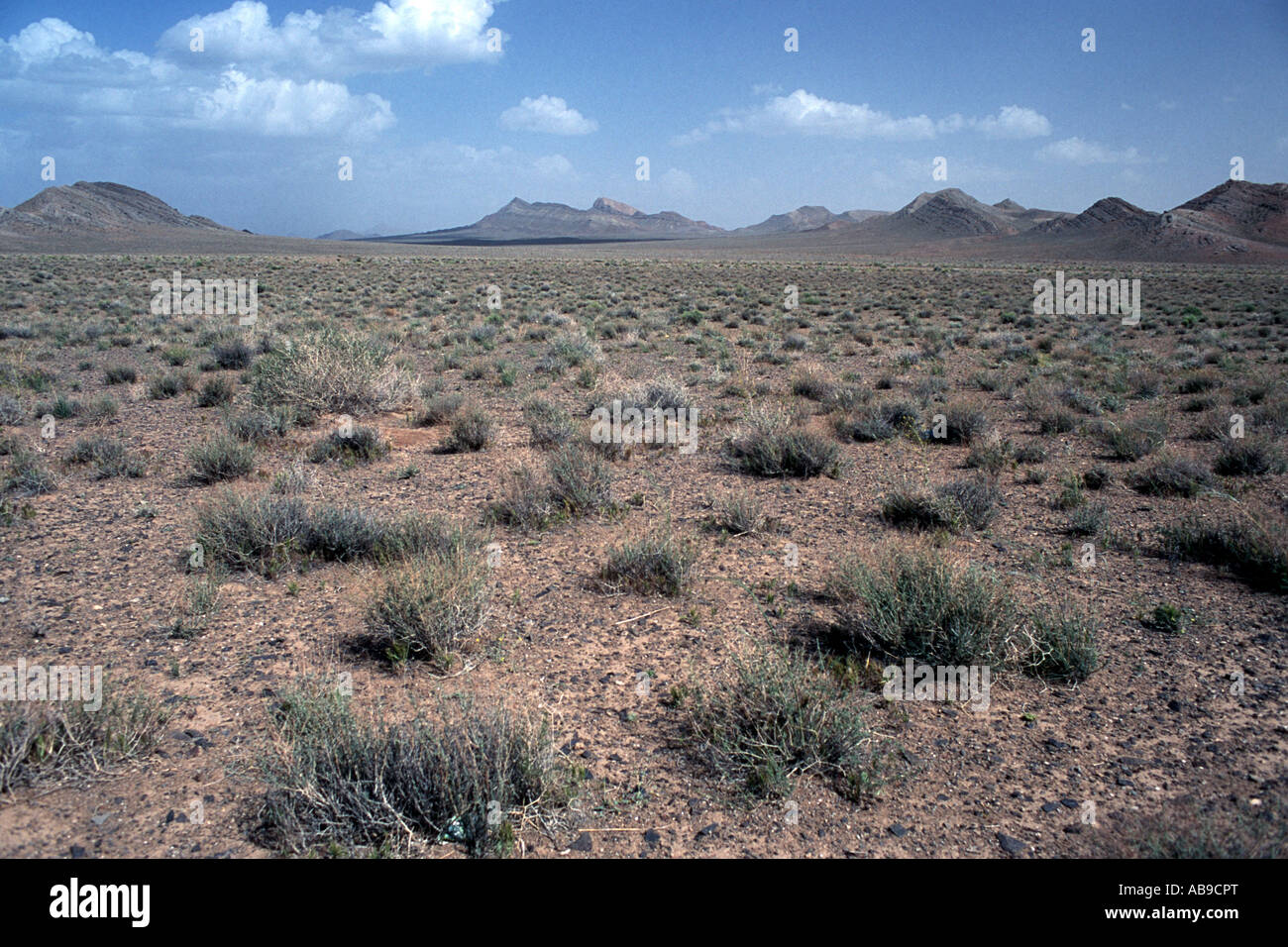

The plants are weird too. Halophytes. These are plants that actually "breathe" salt. They have specialized glands to excrete the excess minerals. If you see a patch of green in the Dasht e Kavir, don’t expect a lush oasis. It’s likely a cluster of scrubby, grey-green bushes that taste like brine.

The Survival Tech of the Ancients

People have lived on the borders of this desert for millennia. How?

Qanats.

This is honestly one of the coolest engineering feats in human history. Instead of trying to find water on the surface, ancient Persians dug underground tunnels that stretched for miles, tapping into mountain aquifers and bringing water to the desert edge using only gravity.

Without qanats, cities like Yazd or Garmsar simply wouldn't exist. These tunnels are so effective that many are still in use today, thousands of years later. They kept the water cool and prevented evaporation, which is the biggest enemy in a place like the Dasht e Kavir desert Iran.

Visiting Without Getting Lost (Literally)

If you’re thinking about going, don’t go alone. This isn't a "rent a Jeep and wing it" kind of trip.

Most travelers start in the village of Mesr or Farahzad. These are tiny outposts that have become hubs for desert tourism. You’ll find traditional guesthouses with thick mud-brick walls that stay naturally cool.

- Garmsar: This is where you see the famous salt mines. The tunnels inside the salt mountains are iridescent.

- Kavir National Park: Often called "Little Africa" because of its wildlife. You need a permit from the Department of Environment to enter certain zones.

- Maranjab Caravanserai: An old Silk Road stopover where you can still spend the night. It sits on the edge of a massive salt lake called Namak.

The best time to visit is between October and March. In the summer, the heat isn't just uncomfortable; it’s lethal. Even in the "cool" months, the sun is incredibly intense. You need high-SPF sunscreen, but more importantly, you need to cover your skin with light, breathable fabrics.

The Reality of Modern Threats

It's not all pristine wilderness. The Dasht e Kavir faces some serious issues.

Climate change is making the already dry area even drier. Groundwater levels are dropping because of over-extraction for farming on the desert's periphery. When the water table drops, the ground sinks. This land subsidence is causing massive cracks to open up in the earth, sometimes miles long.

There's also the issue of soil salinity spreading. As the desert expands, it's pushing into agricultural land. It’s a slow-motion disaster that scientists in Tehran are desperately trying to manage, but when you're fighting the physics of a 77,000 square kilometer salt flat, the odds aren't great.

What Most People Get Wrong

People often conflate the Dasht e Kavir with its neighbor, the Dasht e Lut.

They are very different.

The Lut is home to the Gandom Beryan plateau, which is often cited as the hottest place on the planet's surface. It’s famous for its "Kaluts"—giant sand formations that look like a city of skyscrapers. The Kavir, on the other hand, is flatter, saltier, and more deceptive. While the Lut is a desert of sand and rock, the Kavir is a desert of chemistry and mud.

If you walk on the Lut, you get sand in your shoes. If you walk on the Kavir, you might get salt crystals embedded in your skin.

Getting There and Staying Safe

You’ll likely fly into Tehran first. From there, it’s a few hours' drive southeast.

Hire a local guide who knows the "soft spots." The Kavir is famous for batlagh—quagmire zones where the salt crust looks solid but is actually floating on top of deep, viscous mud. Even heavy 4x4s get stuck here, and if you’re miles from the nearest village, that’s a major problem. Satellite phones are a must because cell service disappears the moment you leave the paved road.

Bring more water than you think you need. Then double it. The dry air wicks moisture off your skin so fast you won't even realize you're sweating. Dehydration hits you like a brick wall.

Actionable Steps for the Desert Traveler

If you are actually planning to see the Dasht e Kavir desert Iran, start with these specific actions:

- Book a guide in Garmsar or Kashan: Do not attempt to drive into the salt flats without a local who understands the seasonal changes in the crust's stability.

- Check the lunar calendar: The salt flats are best experienced during a full moon. The white ground reflects the moonlight so intensely that you can often walk around without a flashlight. It’s an eerie, beautiful experience.

- Visit the Salt Mines of Garmsar first: These are much more accessible than the deep desert and give you a sense of the geological scale of the salt deposits without the risk of getting stranded.

- Pack "onion style" layers: The temperature can drop from 30°C to 5°C in a matter of hours once the sun goes down. Synthetic, moisture-wicking layers are better than cotton.

- Respect the "Rig-e Jenn" boundaries: Even modern expeditions use GPS and specialized equipment to navigate this zone. If you are an amateur, stay on the marked trails near the established caravanserais.

The Dasht e Kavir isn't a place for a casual stroll, but for those who want to see the raw, unfiltered chemistry of the Earth, there is nowhere else like it. It is a reminder of the world’s ancient past and a warning about its dry, salty future.