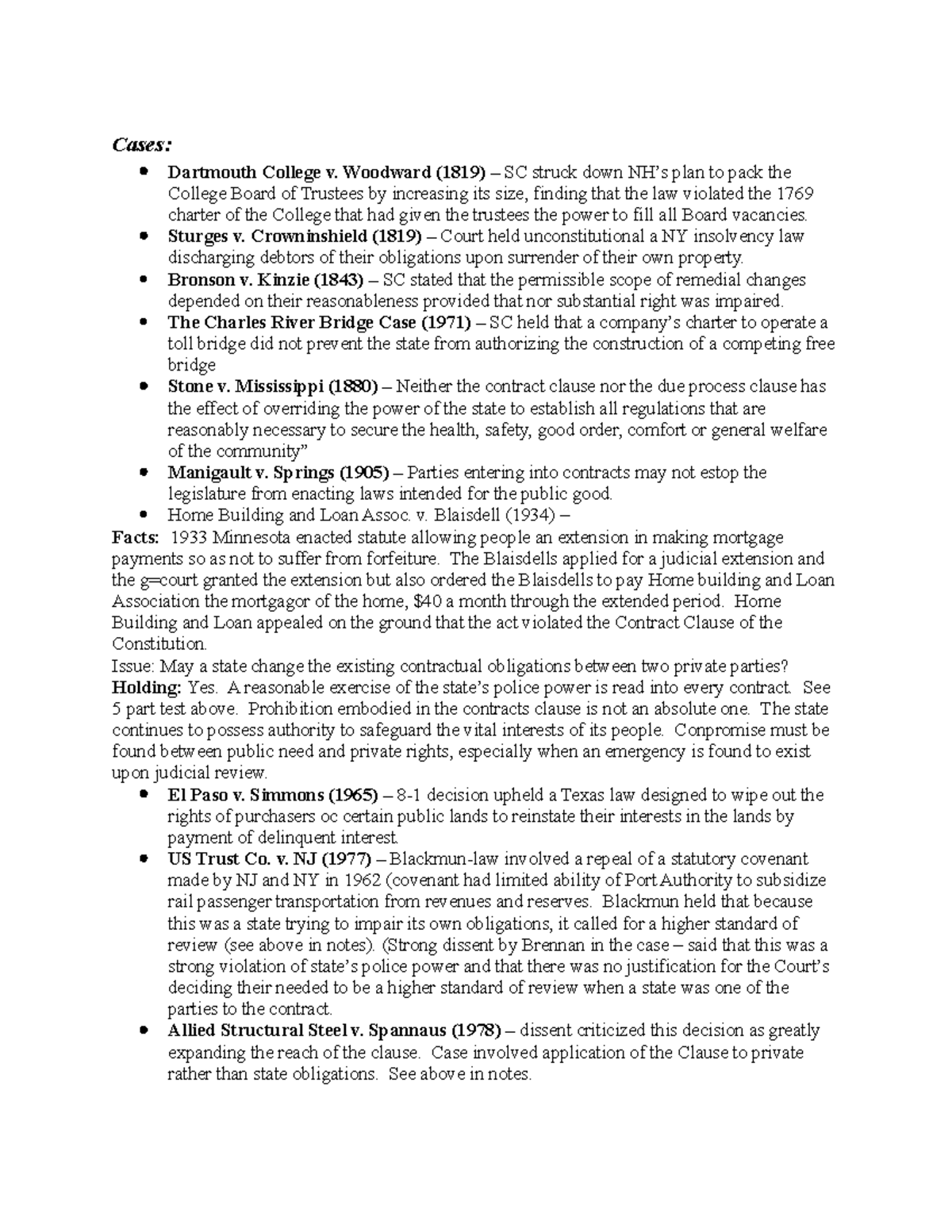

If you’ve ever wondered why the American government can’t just walk into a private company and start changing the board of directors on a whim, you can thank a messy, high-stakes legal battle from over two centuries ago. Honestly, the story of Dartmouth College v. Woodward is less about dusty law books and more about a bitter local grudge that accidentally defined the entire American economy.

It started with a fight over who got to run a small college in the woods of New Hampshire. It ended with the U.S. Supreme Court basically telling every state in the union: "A deal is a deal."

The Grudge That Went to Washington

John Wheelock was the president of Dartmouth in the early 1800s. He wasn't exactly well-liked. He got into a nasty spat with the college trustees, mostly over religious and administrative control. In a fit of pique, the New Hampshire legislature—which was controlled by Jeffersonian Republicans who hated the Federalist-leaning trustees—decided they would just take the school over.

They passed a law in 1816 that turned Dartmouth College into "Dartmouth University." They added new seats to the board and gave the governor the power to fill them. They basically tried to turn a private institution into a state school.

The original trustees weren't having it. They sued William Woodward, the man who held the college seals and records for the new state-backed university. They argued that their original charter, granted by King George III in 1769, was a contract. And under the U.S. Constitution, states aren't allowed to pass laws that mess with contracts.

Daniel Webster’s Tear-Jerker

This is where Daniel Webster enters the frame. He was a Dartmouth alum and a legendary orator. When the case reached the Supreme Court in 1818, Webster spoke for four hours. He didn't just use legal jargon; he made it personal.

He famously said, "It is, sir, as I have said, a small college. And yet there are those who love it!"

🔗 Read more: Johnny Somali AI Deepfake: What Really Happened in South Korea

People in the room supposedly cried. Even Chief Justice John Marshall was moved. But Marshall wasn't just thinking about the feelings of a few New Hampshire graduates. He was looking at the bigger picture of the Contract Clause in Article I, Section 10 of the Constitution.

What the Court Actually Decided

In 1819, the Court ruled 5-1 in favor of the college. Chief Justice Marshall wrote the opinion, and it was a hammer blow to state overreach.

The Court ruled that the college charter was a contract between the King (succeeded by the State) and the trustees. Because it was a contract involving property and "incorporeal hereditaments," the state of New Hampshire couldn't legally change it without both sides agreeing.

This was huge.

Before Dartmouth College v. Woodward, it wasn't entirely clear if a corporation—which is basically a "legal person"—had the same protections as a real person when it came to contracts. Marshall clarified that once a state grants a charter to a private corporation, that charter is protected.

Why It Matters for Your Retirement Account (And Your Job)

You might think, "Cool, a school stayed private. So what?"

💡 You might also like: Sweden School Shooting 2025: What Really Happened at Campus Risbergska

Well, think about the 19th century. This was the era of the Industrial Revolution. People were starting to build railroads, canals, and massive factories. These projects required huge amounts of capital.

Investors are notoriously jumpy. If you were a businessman in 1820, would you put your life savings into building a bridge if you knew the state legislature could just vote to take it over next Tuesday? Probably not.

By ruling in favor of Dartmouth, the Supreme Court created a "safe space" for private investment. It gave corporations a level of security they’d never had before. It told investors that their charters and contracts were safe from the political winds of the day. This decision is often cited by historians as a primary reason the United States was able to industrialize so rapidly. It turned the corporation into the backbone of the American economy.

The Loophole States Found Later

It wasn't all sunshine and roses for corporations, though. After this case, states got smarter. They realized that if they didn't want to be stuck with a "forever contract," they had to change how they issued charters.

If you look at corporate law today, most states include a "reservation of power" clause. Basically, when a state gives a company a charter now, they include a fine-print line that says, "We reserve the right to change our minds or alter this later."

So, while Dartmouth College v. Woodward set the rule that contracts are sacred, the government eventually learned how to write better contracts that kept some power in their hands.

📖 Related: Will Palestine Ever Be Free: What Most People Get Wrong

Modern Echoes: From Tech Giants to Non-Profits

We still see the ghost of this case everywhere. When people talk about "Corporate Personhood"—the idea that a company has legal rights—they are talking about a concept that got a massive boost from Justice Marshall in 1819.

Whether it's a social media platform arguing about its terms of service or a non-profit protecting its endowment, the principle remains: The government cannot easily tear up a private agreement just because the political climate changed.

How to Apply This Knowledge

Understanding this case isn't just for law students. If you're an entrepreneur or a business leader, here are the real-world takeaways:

- Audit Your Foundation: If you operate a business or non-profit, your articles of incorporation are your "charter." Understand what powers you've granted the state in that document.

- The Power of the Contract Clause: Remember that the U.S. Constitution still provides a shield against state laws that "impair the obligation of contracts." If a state or local government tries to retroactively change the terms of a license or agreement you have, this 1819 case is your primary defense.

- Respect the "Reservation of Power": When entering into agreements with government entities, look for clauses that allow them to modify the agreement unilaterally. Unlike the Dartmouth trustees in 1769, you likely have these "escape hatches" for the government built into your modern contracts.

- Vested Rights Matter: The case teaches us that rights, once granted and acted upon, become "vested." If you've invested money based on a government promise or charter, you have a much stronger legal standing than if you're just asking for a new favor.

If you want to dig deeper into how this affects modern property law, I'd suggest looking into the "Charles River Bridge" case of 1837. It shows the flip side—what happens when a corporate charter gets too much protection and starts hurting the public good. It’s the perfect sequel to the Dartmouth drama.

Next Steps for Further Research:

- Read the full text of Chief Justice Marshall’s opinion to see how he defines a "corporation."

- Look up your own state's "Reservation of Power" clause in its corporate code to see how they've adjusted since 1819.

- Compare this case to McCulloch v. Maryland to understand the full scope of the Marshall Court's impact on federalism.