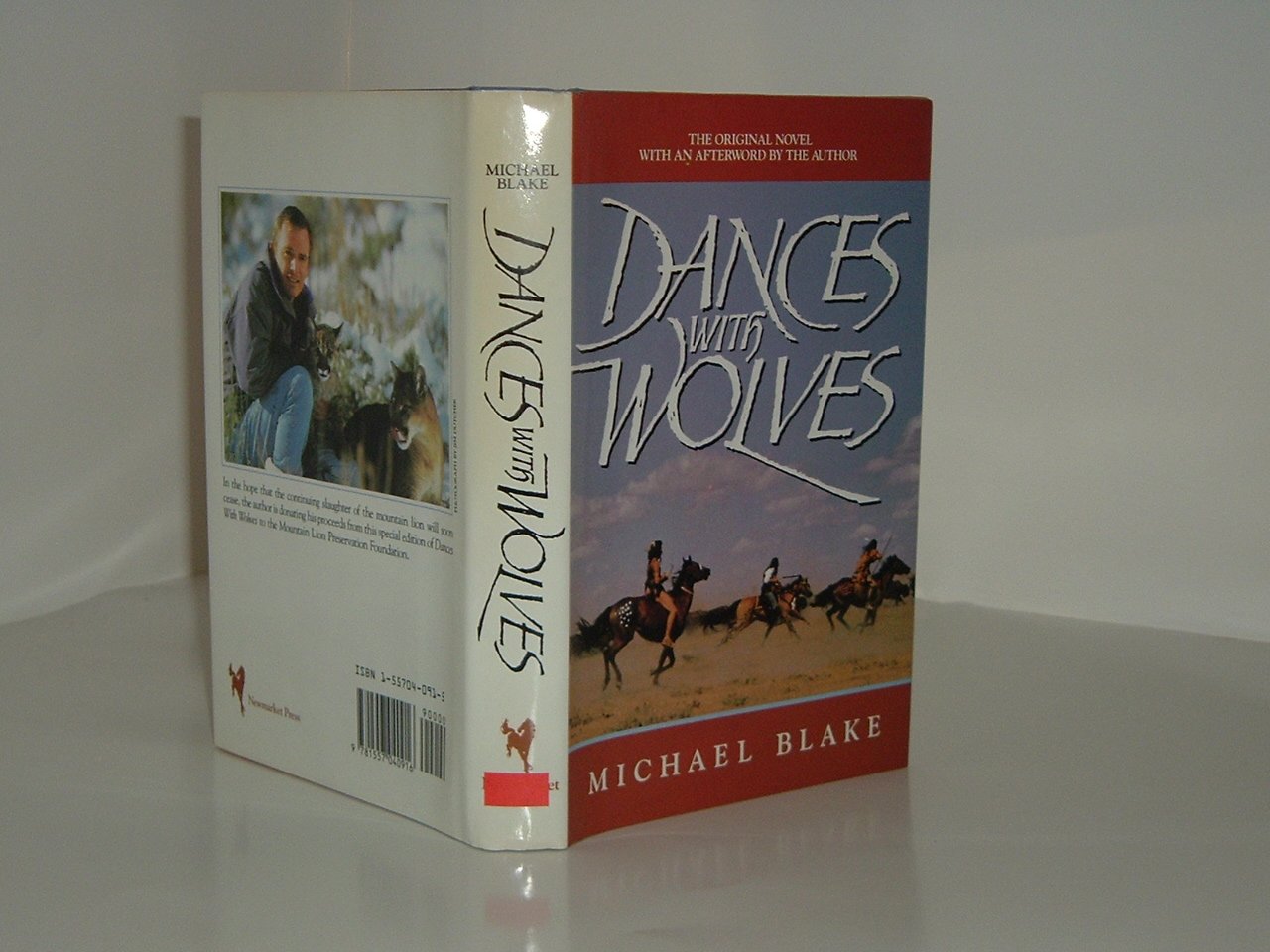

Michael Blake was broke. Honestly, he was more than broke; he was living out of his car, working at a Chinese restaurant, and wondering if his career as a writer had died before it even started. Then he wrote Dances with Wolves by Michael Blake. He didn't know it then, but those pages would eventually win an Academy Award and, more importantly, reshape how millions of people viewed the American frontier.

Most people know the movie. They see Kevin Costner’s face when they think of Lieutenant John Dunbar. But the book? The book is where the soul is. It's grittier. It’s more internal. It’s a story about a man who goes looking for the edge of the world and finds himself instead.

Why Dances with Wolves by Michael Blake was a massive gamble

In the mid-1980s, the Western was dead. Hollywood didn’t want it. Publishers didn’t want it. The genre was considered "dusty" and "outdated," a relic of the John Wayne era that no longer spoke to a modern audience. Blake's script for Dances with Wolves was rejected over thirty times. People told him to turn it into a novel first, basically hoping he’d just go away and stop bothering them with tales of the 1860s.

Blake listened. He struggled through the prose, pouring his obsession with Native American history into a paperback that was eventually published in 1988. It wasn't an immediate sensation. It was a slow burn. But it caught the eye of Kevin Costner, who had worked with Blake on a previous film called Stacy's Knights. Costner saw the potential for something epic. He saw a story that didn't treat the Comanche (who are the primary tribe in the book, though the movie changed them to Lakota Sioux) as faceless villains, but as a complex, vibrant society.

The Dunbar Transformation

The premise is deceptively simple. Lieutenant John J. Dunbar, a Civil War hero who wants to see the frontier "before it's gone," is stationed at an abandoned outpost in the deep wilderness. He’s alone. He has a horse named Cisco and a wolf he calls Two Socks.

What makes the writing in Dances with Wolves by Michael Blake stand out is the pacing of Dunbar’s assimilation. It isn't fast. It’s awkward and dangerous. Blake captures the sensory overload of the plains—the smell of the grass, the terrifying vastness of the sky, and the slow-motion realization that the "savages" he was warned about are actually the only civilized people he’s ever met.

👉 See also: Is Heroes and Villains Legit? What You Need to Know Before Buying

What the movie got wrong (and what the book got right)

If you’ve only seen the film, you’re missing some serious nuance. One of the biggest shifts was the tribe itself. In the book, Dunbar encounters the Comanche. The Comanche were the undisputed masters of the Southern Plains, a "Comancheria" empire that checked Spanish, Mexican, and American expansion for decades. The movie switched them to the Lakota for various production reasons, including location and extra availability, but the book’s focus on the Comanche gives it a different, perhaps sharper, historical edge.

- The character of Stands With A Fist: In the book, her backstory is even more tragic and visceral. Her transition from a white captive to a fully integrated member of the tribe feels more earned in Blake’s prose.

- The Violence: Blake doesn't shy away from the brutality. This isn't a "noble savage" trope. It’s a depiction of a warrior culture that is capable of incredible violence and incredible tenderness.

- The Ending: No spoilers, but the book’s conclusion carries a specific weight of inevitable doom that the movie softens just a tiny bit for the sake of Hollywood's "epic" feel.

Michael Blake spent years researching the habits of the Plains tribes. He wanted to get the details of the buffalo hunt right. He wanted to explain the politics of the council lodge without making it sound like a dry history lecture. He succeeded because he focused on the people—Ten Bears, Kicking Bird, Wind In His Hair—rather than just the archetypes they represented.

The impact on the Western genre

Before Dances with Wolves by Michael Blake, the Western was mostly about conquest. It was about "taming" the land. Blake flipped the script. He made the land the protagonist and the encroaching "civilization" the antagonist.

This book paved the way for more nuanced portrayals of Indigenous cultures in popular media. It wasn't perfect—critics have pointed out the "White Savior" elements that still linger in the narrative—but for 1988, it was a radical departure. It asked the reader to sit in a teepee, to eat raw liver, and to feel the heartbreak of a disappearing world.

Blake’s prose is sparse. It’s not flowery. It reads like a journal, which makes sense given Dunbar’s character. It’s a style that forces you to look at the dirt and the blood. You feel the cold of the Nebraska winter. You feel the thundering vibration of the buffalo herds.

✨ Don't miss: Jack Blocker American Idol Journey: What Most People Get Wrong

A legacy of persistence

Michael Blake’s journey with this story is a lesson in creative grit. He lived in poverty because he refused to give up on this specific vision. When the movie eventually swept the Oscars in 1991, Blake won the Academy Award for Best Adapted Screenplay. It was a vindication for a man who had been told his ideas were obsolete.

But the book remains his true legacy. It’s a deeper, more meditative experience than the film. It allows you to get inside Dunbar’s head as he loses his "whiteness" and becomes something else entirely. He becomes a human being who realizes he's on the wrong side of history.

How to approach reading Michael Blake today

If you're picking up Dances with Wolves by Michael Blake for the first time, or maybe revisiting it after years of watching the DVD, keep a few things in mind. First, look at the date it was written. Some of the language and perspectives are definitely products of the late 80s. However, the core theme—the search for identity in a world that wants to put you in a box—is timeless.

The book is actually part of a trilogy. Many people don't realize that Blake wrote a sequel called The Holy Road in 2001. It picks up years later and deals with the tragic, inevitable collision between the tribe and the US government. It's much darker. It’s a gut-punch of a book that strips away any remaining romanticism about the "Old West."

Actionable Insights for the Reader:

🔗 Read more: Why American Beauty by the Grateful Dead is Still the Gold Standard of Americana

- Read the book first: If you haven't seen the movie, read the book before the visuals of Kevin Costner influence your imagination. The Comanche culture Blake describes is distinct and powerful.

- Research the Comanche: To truly appreciate Blake's work, spend some time reading about the actual Comanche Empire (Pekka Hämäläinen’s The Comanche Empire is a great factual companion). It provides context for the "lords of the plains" that Blake was trying to capture.

- Look for the "lost" chapters: Some editions of the book include notes on Blake’s original drafts. These provide a window into how he pared down the story to its emotional core.

- Explore the sequel: If the ending of Dances with Wolves leaves you wanting more, find a copy of The Holy Road. Just be prepared for a much more somber experience.

Michael Blake’s work reminds us that the stories we tell about our past define our future. He took a "dead" genre and breathed life back into it by simply telling the truth about the human heart’s desire for connection. Whether it's a man and a wolf or a man and a culture not his own, the book is about the bridges we build. Sometimes those bridges are burned down by history, but Blake ensures we remember they existed.

The best way to honor this narrative is to look beyond the Hollywood spectacle and engage with the text itself. The wind on the prairie still speaks if you’re quiet enough to listen. Blake was listening, and he wrote down what he heard.

Check your local library or a used bookstore for an original 1988 mass-market paperback. There is something about reading this story in its original, unpretentious format that fits the rugged, unvarnished nature of Dunbar’s journey. Read it outside. Read it where you can see the horizon. It changes the way the words hit the page.

Once you finish the novel, compare the internal monologues of Dunbar in the book to the voiceover in the film. You’ll notice that the book offers a much more conflicted, often grimmer view of his own desertion and his "new" life. It’s a masterclass in character development that doesn't rely on easy answers.

Finally, take a moment to look into Michael Blake’s other works, like Airman Mortensen. He wasn't a one-hit wonder; he was a writer deeply concerned with the individual's place in a massive, often uncaring system. That theme started with a lonely soldier at Fort Sedgewick and it defines his entire bibliography.