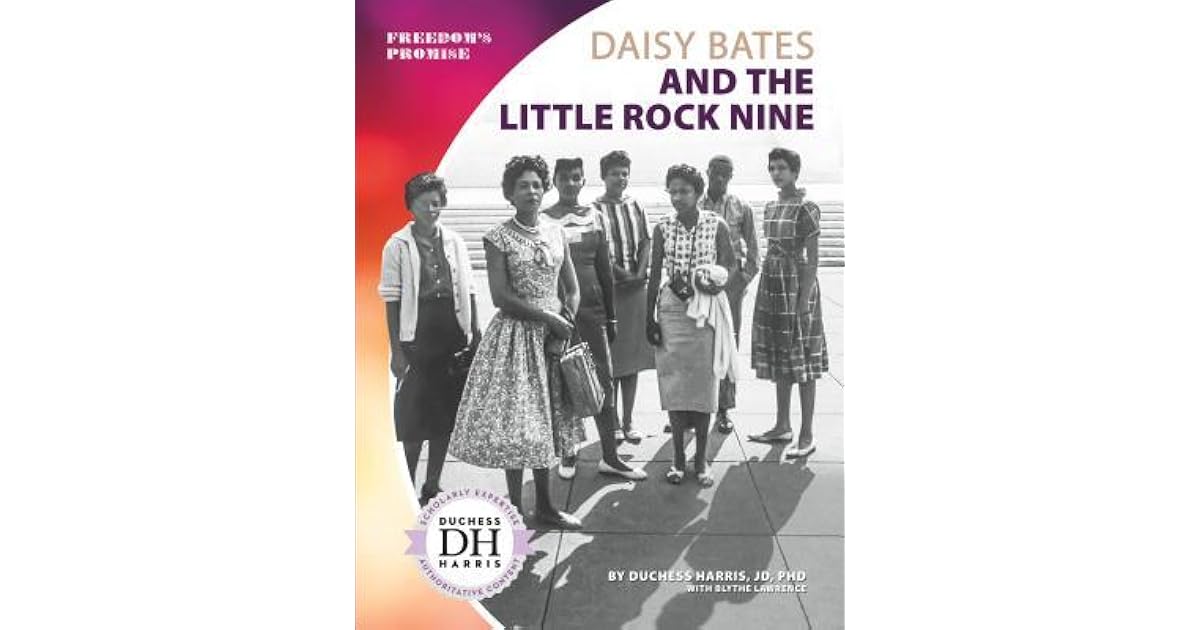

History books love a good photo. They usually show Elizabeth Eckford, stone-faced and wearing those dark sunglasses, while a screaming white girl follows her down the street in 1957. It’s iconic. But honestly? Most of us miss the person who actually orchestrated that entire standoff from a living room couch.

That person was Daisy Bates.

If you think the integration of Central High School was just a spontaneous burst of student bravery, you're missing the most interesting part of the story. It was a calculated, dangerous, and incredibly messy political chess match. Daisy Bates and the Little Rock Nine didn't just happen; they were a movement forged by a woman who had every reason to hate the system that eventually called her a hero.

The Trauma That Built a Leader

Daisy Bates wasn't some polished politician from the North. She was born in Huttig, Arkansas, a tiny mill town. When she was only three, her mother was murdered by three white men. Her father fled, and she was raised by family friends. Imagine growing up in a town where everyone knows who killed your mother, but the law just looks the other way.

That stays with a person.

She eventually married L.C. Bates, and together they moved to Little Rock to start the Arkansas State Press. It wasn't just a newspaper. It was a weapon. They used it to call out police brutality and judicial bias. By the time the Brown v. Board of Education ruling dropped in 1954, Daisy was already the president of the Arkansas NAACP. She wasn't waiting for permission to change things.

What Actually Happened at 1207 West 28th Street

People talk about the "headquarters" of the civil rights movement in Arkansas. Usually, that’s code for Daisy’s house.

🔗 Read more: When Does Joe Biden's Term End: What Actually Happened

The nine students—Ernest Green, Elizabeth Eckford, Jefferson Thomas, Terrence Roberts, Carlotta Walls LaNier, Minnijean Brown, Gloria Ray Karlmark, Thelma Mothershed, and Melba Pattillo Beals—weren't just random kids. They were vetted. They had to have the grades, the temperament, and the sheer "guts" to walk into a building where thousands of people wanted them dead.

Daisy’s home became their bunker.

They met there every morning. They ate there. They practiced how to keep their heads down while people spat on them. While the world watched the soldiers at the school gates, Daisy was at home dealing with rocks being thrown through her windows and crosses being burned on her lawn.

"Any time it takes eleven thousand five hundred soldiers to assure nine Negro children their constitutional rights in a democratic society, I can't be happy." — Daisy Bates

She said that because she knew the federal troops were just a band-aid. The 101st Airborne Division, sent by President Eisenhower, could stop a mob, but they couldn't stop the girl in the bathroom from dropping burning paper on Melba Pattillo's head.

The Messy Reality of Integration

We like to think that once the "Nine" got inside, the battle was won. Kinda the opposite, actually.

💡 You might also like: Fire in Idyllwild California: What Most People Get Wrong

The 1957-1958 school year was a nightmare. Inside those walls, the students were isolated. The soldiers couldn't go into the bathrooms or the locker rooms. That’s where the real damage happened. Acid thrown in eyes. Kicks. Constant, soul-crushing verbal abuse.

Daisy was the one who had to take the 2:00 AM phone calls from terrified parents. She was the one who pushed the school board when they tried to expel the Black students for defending themselves. When Minnijean Brown finally got expelled for "retaliating" (she dropped a bowl of chili on a harasser), Daisy was the one who helped her find a school in New York so she could actually graduate.

And let's be real about the cost.

The Arkansas State Press—Daisy and L.C.'s life's work—was destroyed. White businesses pulled their advertising. The paper went bankrupt because they refused to stop supporting the integration. They lost their livelihood for a cause that didn't even pay them.

Why We Get the Ending Wrong

Most people think the story ends with Ernest Green graduating in 1958.

It doesn't.

📖 Related: Who Is More Likely to Win the Election 2024: What Most People Get Wrong

Governor Orval Faubus was so angry about losing that he literally shut down every high school in Little Rock the following year. They called it "The Lost Year." He figured if Black kids couldn't be kept out, nobody would go to school at all.

Daisy Bates didn't quit. She kept organizing. She moved to D.C. for a while to work for the LBJ administration on anti-poverty programs, but she eventually came back to Arkansas. She spent her later years in Mitchellville, helping a poor Black community build a water system and a community center.

Actionable Insights: Lessons from the Front Lines

You don't have to be facing down the National Guard to learn from Daisy Bates. Her life offers a blueprint for how to actually move the needle on big, systemic problems:

- Build the "Bunker" First: You can't lead a movement from a vacuum. Daisy made her home a safe space where the Little Rock Nine could be kids before they had to be icons. Community is the fuel for courage.

- The Medium is the Message: The Arkansas State Press was essential. Without a way to tell their own story, the narrative would have been controlled by those who wanted to keep the status quo. If you want change, you need a platform you control.

- Vulnerability is a Strategy: Daisy knew that the image of a lone student (Elizabeth Eckford) facing a mob would change the world. She didn't hide the struggle; she made sure the world saw the ugliness of the resistance.

- Prepare for the Long Game: Integration wasn't a "day." It was a year of torture followed by a year of closed schools. True change requires the stamina to stay in the fight after the cameras leave.

If you ever find yourself in Little Rock, don't just look at the statues. Go to the Daisy Bates House. It’s a National Historic Landmark now. It’s a quiet, unassuming place, but it’s where a handful of teenagers and one very determined woman decided that "gradual" progress wasn't good enough.

They didn't just break a law; they broke a system.

To truly understand this era, you should read Daisy’s own memoir, The Long Shadow of Little Rock. It’s not a dry history book; it’s a raw account of what it feels like to be at the center of a storm. You can also visit the Little Rock Central High School National Historic Site, which is still a functioning high school today. Seeing those front steps in person puts the scale of their bravery into perspective.