The waves off the coast of Douarnenez don't just crash; they whisper. If you ask a local fisherman in Finistère about the bells, they’ll likely give you a knowing look or a shrug that says more than words ever could. They're talking about the Daughters of Ys, specifically the princess Dahut, whose legacy is literally submerged in the Atlantic. It’s a story of a city built below sea level, a father’s love, and a catastrophic flood that makes the story of Atlantis look like a puddle. Honestly, the tale is a messy mix of Celtic paganism and early Christian morality, and it’s arguably the most important piece of folklore in Breton culture.

People often get the details wrong. They think it’s just a simple "don't be a sinner" story. It isn't.

The legend centers on King Gradlon and his daughter, Dahut. Depending on which version of the medieval manuscript you’re reading—or which local storyteller is nursing a cider at the pub—the Daughters of Ys (often simplified to the singular Dahut) represent the tension between the old world and the new. Ys was a marvel. To keep the ocean out, Gradlon built a massive dike with a single bronze gate. Only the King had the key. He wore it around his neck. You can probably guess where this is going.

What Really Happened to the Daughters of Ys

Dahut wasn't just some spoiled royal. In the older, more "un-scrubbed" versions of the myth, she’s a powerful figure connected to the sea-gods. She loved the ocean. She hated the stifling influence of Saint Winwaloe, who was constantly nagging her father to make the city more "pious."

One night, a "Red Knight" arrives. He’s charming, he’s mysterious, and he’s almost certainly the devil in a very stylish cloak. He convinces Dahut to steal the silver key from her sleeping father’s neck. Why? Because she wanted to open the gates and let the sea in to dance? Or maybe because he tricked her? Either way, the bronze doors swung open. The Atlantic didn't just leak in; it roared.

Gradlon woke up to a nightmare. He hopped on his magical horse, Morvarc'h, and grabbed his daughter to flee the rising tide. But the horse couldn't carry both of them through the churning surf. Saint Winwaloe, watching from a safe distance, shouted at the King to "push the demon off." Gradlon, in a moment of sheer survival instinct or perhaps religious possession, threw his own daughter into the waves.

The sea claimed her. The city vanished. Gradlon survived to found Quimper, but the Daughters of Ys became something else entirely.

The Morgen and the Shifting Narrative

Once Dahut hit the water, she didn't just drown. Legend says she became a Morgen—a siren-like creature doomed to lure sailors to their deaths. This is where the story gets really interesting from a historical perspective.

🔗 Read more: Pink White Nail Studio Secrets and Why Your Manicure Isn't Lasting

Early Breton accounts don't treat her as a villain. She was a symbol of the sea's wildness. It was only later, as Christianity gripped the region, that the Daughters of Ys were reframed as a cautionary tale about female vanity and "sinful" living. Scholars like Amy Varin have pointed out that Dahut’s transformation into a mermaid-like figure mirrors other Celtic deities who were demoted to monsters by the Church.

It’s a pattern. Ancient gods become devils. Powerful women become hags or sirens.

Think about the geography for a second. The Bay of Douarnenez is shallow. At low tide, you can see rock formations that look suspiciously like ruins. This isn't just a campfire story; it’s a legend built on the physical reality of a coastline that has been changing for thousands of years. Geologists have actually found evidence of ancient settlements that were submerged as sea levels rose after the last ice age. The "sunken city" isn't a total myth; it’s a memory.

Why the Legend Won't Die

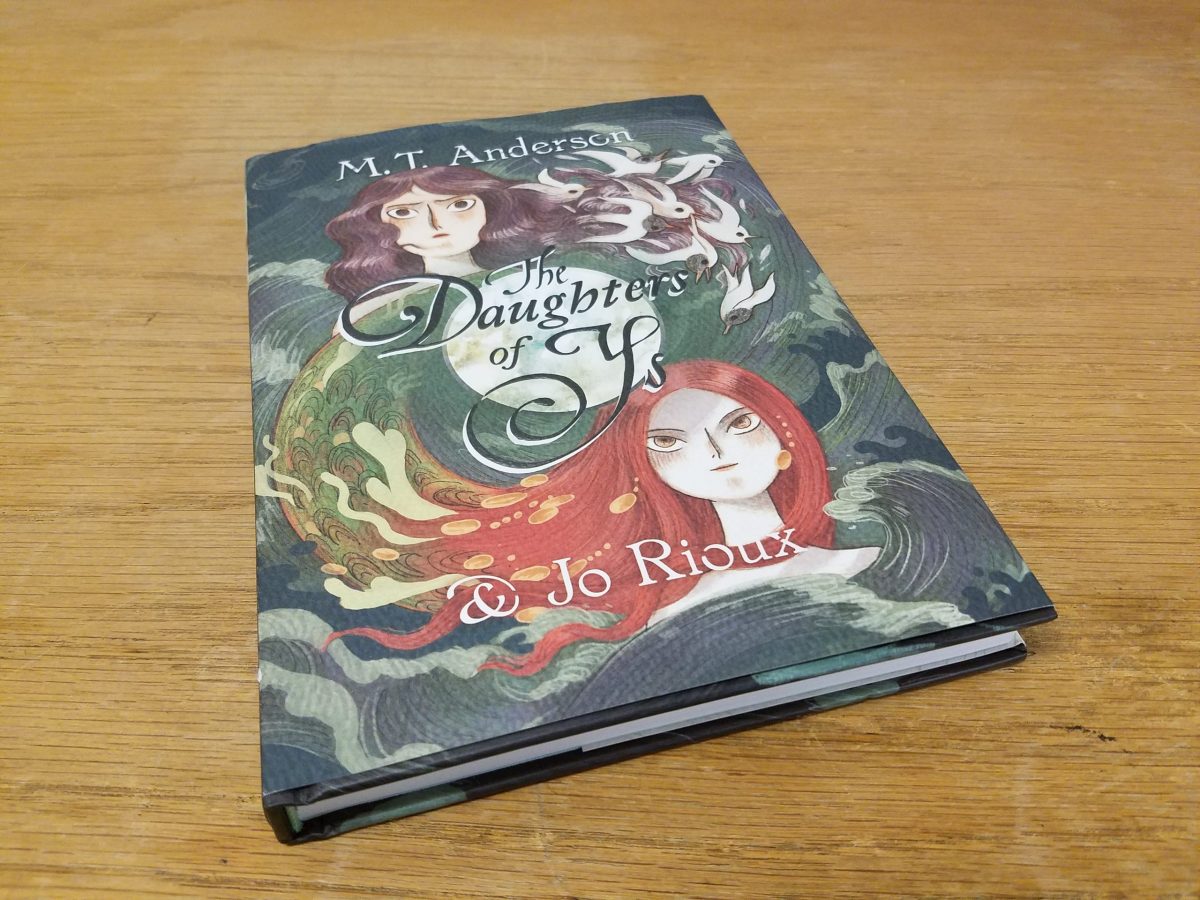

You see Dahut’s influence everywhere in Brittany today. She’s on posters, in graphic novels, and she’s the subject of the famous opera Le Roi d'Ys by Édouard Lalo. The fascination persists because the story hits on universal fears: the loss of a child, the betrayal of a parent, and the terrifying power of the ocean.

But there’s a darker side to the Daughters of Ys that most tourist brochures skip.

In some versions, Dahut used a magic mirror to see her lovers, only to kill them and toss them into the sea once she was bored. It’s gritty. It’s violent. It’s a far cry from the Disney-fied versions of folk tales we usually get. This darker edge is why the story still resonates. It’s a reflection of the brutal, rocky coast where it was born.

The city of Ys is said to be the most beautiful city in the world. People say that when Paris was founded, it was named Par-Is, meaning "like Ys." That’s almost certainly a folk etymology (linguists usually disagree), but it shows how highly the Bretons regarded their lost capital.

💡 You might also like: Hairstyles for women over 50 with round faces: What your stylist isn't telling you

Spotting the Influence Today

If you visit the Cathedral of Saint Corentin in Quimper, look up. You’ll see an equestrian statue of King Gradlon sitting between the two spires. He’s looking back toward the sea, toward the daughter he abandoned and the city he lost. It’s a haunting image.

The Daughters of Ys are also a staple in modern fantasy literature and gaming. You can see echoes of Dahut in characters from The Witcher or even in the lore of various "sunken kingdom" expansions in RPGs. The archetype of the "fallen princess of the waves" is a goldmine for storytelling.

But for the people of Brittany, it’s deeper. It’s about identity.

The Breton language, the music, the traditions—they’ve all faced "floods" of their own from outside influences. Dahut represents the part of the Breton soul that refuses to be tamed by the Church or the State. She is the wild, paganish heart of the West.

Modern Interpretations and Reclaimed History

Recently, there’s been a shift in how we talk about the Daughters of Ys. Feminists and folklorists are looking at Dahut through a different lens. Was she really a "sinner," or was she just a woman who refused to follow the strict rules of a new religion?

When you read the 19th-century collections by Théodore Hersart de La Villemarqué in his Barzaz Breiz, the bias is obvious. He was trying to preserve the culture, but he was also a man of his time. He painted Dahut as a figure of lust and ruin.

Modern writers are flipping the script. They see her as a protector of Breton heritage. They see the flooding of Ys not as a punishment, but as a tragic clash of cultures.

📖 Related: How to Sign Someone Up for Scientology: What Actually Happens and What You Need to Know

It makes you wonder. What else have we buried under the waves of "official" history?

The Atlantic is cold. It's deep. It keeps its secrets well. But as long as the tide comes in and out, the story of the Daughters of Ys will keep washing up on the shore, reminding us that the past is never truly gone. It’s just waiting for the right person to find the key.

How to Explore the Legend Yourself

If you’re actually interested in the "real" Ys, you can’t just go to a museum. You have to experience the landscape. It’s the only way to get the vibe.

- Visit the Bay of Douarnenez: Go at sunset. The light hits the water in a way that makes you swear you can see the tops of towers just beneath the surface.

- Quimper Cathedral: Check out the statue of Gradlon. It’s the best physical monument to the legend.

- Read the Barzaz Breiz: Even with its biases, it’s the definitive collection of Breton folk songs and stories. It’s where the "modern" version of the myth was solidified.

- Listen to Lalo’s Opera: If you want the high-drama, 19th-century version of the tragedy, this is it. The overture alone is enough to give you chills.

- Look for the "Pointe du Raz": This jagged cliffside is where the land literally ends. It’s easy to imagine a city being swallowed by the sea here.

The legend of the Daughters of Ys isn't just a story for the history books. It’s a living part of the landscape. It’s in the salt spray and the granite rocks. Honestly, once you’ve stood on that coast and felt the wind, you’ll stop questioning if the city existed. You’ll just wonder why it took so long for the sea to reclaim it.

The next time someone mentions a sunken city, don't think of Greece. Think of the gray waters of Brittany and the princess who chose the ocean over the shore.

To dive deeper into the actual history of the region, look into the archaeological surveys of the Breton coast. There are several ongoing projects mapping submerged Neolithic sites that provide a fascinating, if less romantic, backdrop to the myth. You can also check out the local maritime museums in Brest which often have exhibits on the relationship between Breton folklore and the sea. If you're traveling there, try to time your visit for one of the local "Pardons"—traditional festivals where the line between religious ceremony and ancient folklore is incredibly thin. That's where you'll find the real heart of the story.