Cuba is complicated. If you ask three different people in Havana or Miami about the Día de la Independencia de Cuba, you’re probably going to get four different answers. It’s not like the Fourth of July in the States where everyone just agrees on the date and flips some burgers. For Cubans, May 20 is a day wrapped in layers of pride, frustration, and a massive amount of political baggage.

Most people think independence happened once. It didn't. It was a messy, decades-long slog against Spain, followed by a weird, "it's complicated" relationship with the United States.

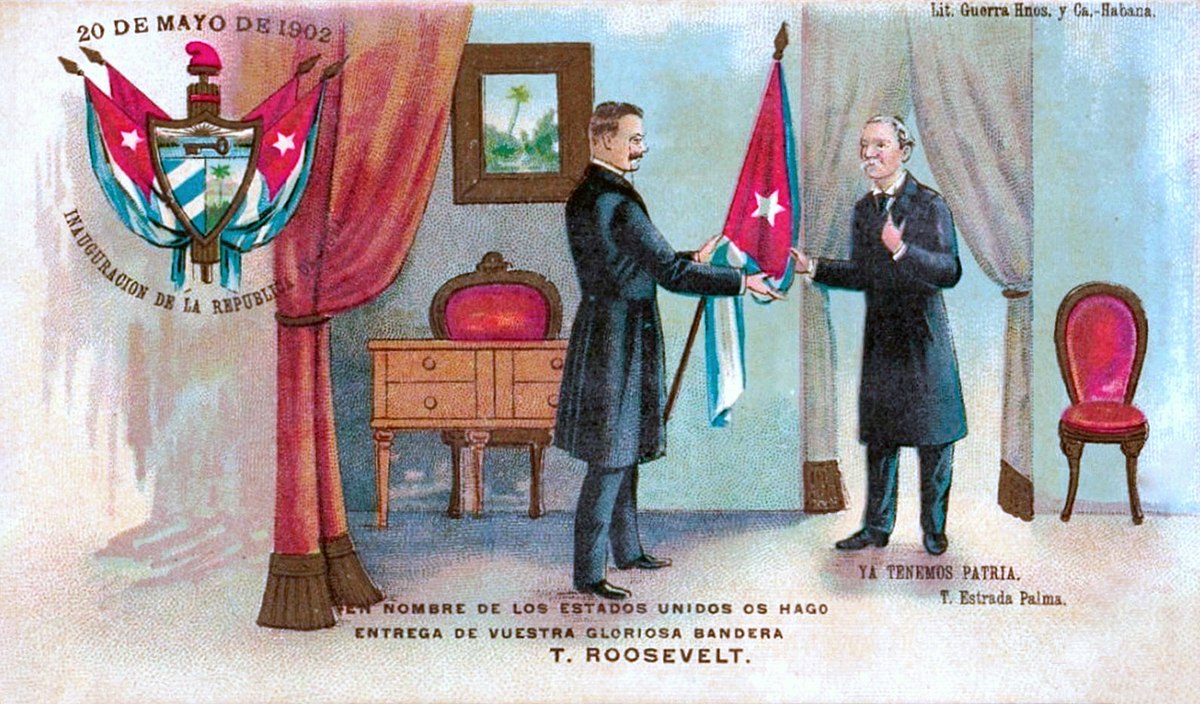

May 20, 1902, was the day the island officially became a republic. The red, white, and blue flag was raised over the Castillo de los Tres Reyes del Morro in Havana. General Leonard Wood, the military governor, basically handed over the keys to Tomás Estrada Palma, the first president. But here’s the kicker: it wasn't total freedom. Not by a long shot.

The 1902 Reality Check

History books often gloss over the fact that Cuba’s independence was birthed with a giant asterisk attached to it. That asterisk was the Platt Amendment.

Imagine winning a marathon but being told you can only drink water if your neighbor says it's okay. That was Cuba in 1902. The U.S. insisted that the Platt Amendment be written right into the Cuban Constitution. It gave Washington the legal right to intervene in Cuban affairs whenever they felt things were getting "unstable." It also secured the land for the Guantanamo Bay naval base.

💡 You might also like: Finding the Right Birthday Quotes for Sister in Law Without Sounding Like a Greeting Card

Because of this, many modern historians and the current Cuban government don’t actually view May 20 as the "true" independence day. They see it as the start of a neo-colonial period.

If you go to Cuba today, you won't see massive parades on May 20. The government there puts the spotlight on October 10—the Grito de Yara—when Carlos Manuel de Céspedes freed his slaves and started the first war against Spain in 1868. Or, obviously, January 1, the anniversary of the 1959 Revolution.

But for the diaspora, especially in places like Little Havana in Miami, May 20 remains a massive deal. It represents the Republic. It represents a Cuba that existed before the Castros.

Why the Ten Years' War Changed Everything

Before 1902 could even happen, the island had to bleed. A lot.

The Ten Years' War (1868–1878) was a brutal, grinding conflict. It started because wealthy plantation owners were tired of Spanish taxes and zero representation. But it turned into something much bigger. It was the first time "Cubanness" really started to mean something across racial lines. Black, white, and Chinese Cubans fought together in the Mambi Army.

Names like Antonio Maceo—the "Bronze Titan"—became legendary. Maceo was a Afro-Cuban general who rose through the ranks because he was, frankly, terrifying on the battlefield. He refused to sign the Pact of Zanjón because it didn't guarantee the abolition of slavery.

That’s the kind of grit that led to the eventual Día de la Independencia de Cuba. It wasn't just handed over in a boardroom in D.C.; it was earned in the jungles of Oriente.

The Martí Factor

You can't talk about Cuban independence without talking about José Martí. He’s everywhere. Statues, busts, murals, airports.

Martí was a poet, a journalist, and a revolutionary who spent most of his life in exile, much of it in New York City. He was the one who unified the old generals from the previous wars and the new generation of rebels. He founded the Cuban Revolutionary Party.

He died in 1895, right at the start of the final war of independence, falling off his horse during the Battle of Dos Ríos. He never saw the Republic born in 1902. Some say that was a mercy. Martí was deeply wary of U.S. intentions. He famously wrote about "the monster" in whose entrails he lived.

His vision for Cuba was a "republic with all and for the good of all." When 1902 finally rolled around, many felt the result—a republic shackled by the Platt Amendment—was a betrayal of everything Martí stood for.

The US Intervention: Hero or Spoiler?

The Spanish-American War in 1898 is usually how Americans remember this era. The USS Maine blows up in Havana Harbor, Teddy Roosevelt charges up San Juan Hill, and Spain loses its empire.

But for Cubans, this was the "Spanish-Cuban-American War."

The Cuban rebels had already exhausted the Spanish army by the time the Americans showed up. Then, the U.S. excluded the Cuban generals from the surrender negotiations in Paris. It was a snub that set the tone for the next fifty years.

Honestly, the relationship between the two countries has been a roller coaster ever since. The 1902 independence was the first peak of that ride.

How People Celebrate Today

The celebration of Día de la Independencia de Cuba is basically a tale of two cities.

In Miami, May 20 is a festive explosion. You’ve got Calle Ocho filled with people wearing Guayaberas. There are concerts, political speeches, and enough Cuban coffee to power a small jet. It's a day of nostalgia. It’s about remembering a homeland that, for many, only exists in stories told by their grandparents.

In Havana? It's a normal Tuesday. Or Thursday. Whatever day it happens to fall on.

The official line in Cuba is that "true" independence didn't happen until 1959 when Fidel Castro’s forces entered Havana. They view the 1902 Republic as a "pseudorepublic."

It’s a fascinatng case of how history is written by whoever holds the pen. One group sees 1902 as the birth of a nation; the other sees it as a false start.

Food and Tradition

Regardless of the politics, Cuban identity is tied to the table. When people do celebrate the spirit of independence, whether on May 20 or October 10, the menu is non-negotiable.

- Lechón Asado: Roast pig, marinated in mojo (garlic, sour orange, oregano).

- Congrí: Rice and black beans cooked together. It’s a staple.

- Yuca con Mojo: Cassava with that same garlic sauce.

- Tostones: Fried green plantains.

Food is the one thing that bridges the gap between the island and the diaspora. You might disagree on the significance of 1902, but you’re not going to turn down a plate of slow-roasted pork.

The Economics of Independence

We often forget that the drive for the Día de la Independencia de Cuba was as much about sugar as it was about liberty.

In the late 1800s, Cuba was the world's sugar bowl. Spain was draining the island’s wealth while the U.S. was becoming the biggest buyer. The business class in Cuba realized they were tethered to a dying European empire while their future was clearly with the rising power to the north.

This economic tension is what made the 1902 Republic so fragile. American companies bought up huge swaths of land for sugar mills. By the 1920s, the Cuban economy was basically a subsidiary of Wall Street.

This is the nuance many people miss. Independence isn't just about having your own flag. It's about who owns the soil.

Misconceptions to Clear Up

People often confuse the 1902 independence with the 1959 revolution. They are totally different animals.

1902 was about breaking away from Spain.

1959 was about overthrowing a domestic dictator (Batista) and, eventually, breaking away from U.S. influence.

Another big one: many think the U.S. "gave" Cuba independence. The reality is that Cubans had been fighting Spain for thirty years. The U.S. intervention was the final blow, but the groundwork was laid by Cuban blood.

Why 1902 Still Matters in 2026

You might wonder why we’re still talking about a date from over a century ago.

It’s because the "Cuban Question" is still unanswered. The island is currently going through its worst economic crisis in decades. Migration is at an all-time high. People are looking back at history to try and find a roadmap for the future.

The dream of 1902—a sovereign, democratic, and prosperous Cuba—remains the goal for millions. Whether you call it the "Republic" or the "Pseudorepublic," the desire for self-determination that fueled Martí and Maceo hasn't gone anywhere.

Actionable Insights for the History Buff or Traveler

If you want to truly understand the Día de la Independencia de Cuba, don't just read one book. Look at both sides.

- Visit the Museum of the Revolution in Havana: It’s housed in the former Presidential Palace. You’ll see the 1959 perspective, but the building itself is a relic of the Republic era.

- Explore the American Side: Read the text of the Platt Amendment. It’s dry, but it explains almost everything about why U.S.-Cuba relations are so toxic today.

- Talk to the Elders: If you’re in Miami, go to Domino Park. Talk to the guys playing. They remember the stories their parents told them about the old Republic.

- Read Martí’s "Versos Sencillos": It’ll give you a sense of the soul of the independence movement beyond the dates and battles.

The story of Cuban independence is still being written. 1902 was just a very loud, very complicated first chapter.

To get a real feel for the era, look into the life of General Máximo Gómez. He was a Dominican who became the head of the Cuban Liberating Army. He famously said, "The Cubans either don't reach the goal, or they pass it." He was skeptical of the 1902 transition, and his journals provide some of the most honest accounts of the time.

Understanding this day means acknowledging the beauty of the flag raising and the shadow cast by the foreign policy that followed. It’s not a simple holiday. It’s a reflection of a nation’s ongoing struggle to define itself.