You’re standing at the base of a 90-foot white pine. It’s leaning. Not a "maybe it’ll be fine" lean, but a "this thing is eyeing my roof" lean. Your neck hurts just looking at the canopy. Honestly, most people think cutting down huge trees is just about a sharp chainsaw and a prayer, but that’s exactly how houses get crushed. I’ve seen it. Total chaos because someone underestimated the weight of a single limb.

Gravity is a beast.

When you’re dealing with a specimen that weighs ten tons, you aren’t just "cutting." You are managing a massive amount of potential energy that wants to turn kinetic in the worst way possible. If you mess up the notch, the tree doesn't just fall; it can "barber chair," splitting vertically up the trunk and kicking back with enough force to liquefy a person. It’s gruesome. It’s real. And it’s why professional arborists spend years learning how to read wood grain like a book.

The Physics of Taking Down a Giant

People always ask about the "felling notch." They think it’s just a triangle you hack into the side. It isn't. According to the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), logging is consistently one of the most dangerous jobs in the United States, and it's because of the physics involved in the face cut.

You need a proper open-face notch—ideally 70 to 90 degrees. This allows the tree to stay attached to the "hinge" longer as it falls. If your notch is too shallow, the hinge breaks too early. Then? You lose control. The tree can go anywhere. It can catch the wind and pivot. It can bounce off a neighboring oak and come flying back at you like a possessed toothpick.

Why the Hinge is Your Only Friend

The hinge is that strip of uncut wood between your notch and your back cut. It acts like a door hinge. It guides the tree. You never, ever cut all the way through. If you do, you've just disconnected a multi-ton weight from the earth with no steering wheel. Experts like those at the TCIA (Tree Care Industry Association) emphasize that hinge thickness should generally be about 10% of the tree's diameter.

But wood isn't perfect.

A tree might look solid but be hollowed out by Armillaria root rot or heart rot. You start cutting, and suddenly the "solid" wood is just mush. At that point, your hinge is useless. You’re basically playing Jenga with a live bomb. This is why pros use sounding hammers or even sonic tomograph tests on high-value or high-risk removals. They need to know if the "bones" of the tree are actually there before they commit to a back cut.

✨ Don't miss: 100 Biggest Cities in the US: Why the Map You Know is Wrong

The Hidden Danger of Tension and Compression

Cutting down huge trees isn't just about the trunk. The canopy is a tangled mess of spring-loaded traps.

Think about "widowmakers." These are dead branches hanging loose in the upper atmosphere of the tree. The vibration of a chainsaw is often enough to shake them loose. They fall silently. No warning. Just a five-hundred-pound log dropping from 60 feet up. Even with a hard hat, that’s a closed casket scenario.

Then you have "sidewinders." When a tree falls and gets hung up in another tree, the tension is astronomical. If you try to cut it down without knowing how to release that tension, the trunk can "spring" sideways. It happens in a millisecond. Faster than you can blink.

- Pressure side: Where the wood is being squished.

- Tension side: Where the fibers are being pulled apart.

If you cut the tension side first, the wood will rip and splinter. If you cut the pressure side first, your saw gets pinched. You’re stuck. Now you have a stuck saw in a leaning giant. That’s a bad day.

Cranes, Ziplines, and Surgical Removals

In tight suburbs, you can’t just "drop" a tree. There’s no space. You’ve got power lines, your neighbor’s prized gazebo, and a swimming pool all in the "kill zone." This is where the art of rigging comes in.

Modern arboriculture uses high-tensile ropes (like Yale Cordage or Samson Rope) and friction devices called Port-a-Wraps. A climber goes up, pieces out the tree limb by limb, and lowers them down. It’s slow. It’s expensive. But it’s the only way to do it without wrecking the neighborhood.

Sometimes, we bring in the big guns: a 100-ton crane.

🔗 Read more: Cooper City FL Zip Codes: What Moving Here Is Actually Like

The crane holds the top of the tree while the arborist cuts it. The crane then lifts the entire section over the house and sets it down in the street. It looks like magic. It’s actually just very expensive math. The crane operator has to know the weight of the wood—green oak weighs about 63 pounds per cubic foot. If the operator underestimates the weight of a 20-foot section, the crane can tip. Look up "crane accidents tree removal" on YouTube if you want to see how fast $500,000 of machinery can be destroyed.

The Reality of the Cost

Why does it cost $3,000 to remove one tree?

Insurance.

Tree work insurance is some of the most expensive in the world. A "cheap" guy with a truck and a saw usually doesn't have it. If he gets hurt on your property, or if he drops a limb through your kitchen ceiling, you’re the one who pays. Most homeowners' policies have exclusions for "damage caused by an unlicensed contractor." You’re left holding the bag.

A legitimate company has:

- Workers' Comp: Because falls and cuts happen.

- General Liability: Usually $1 million to $2 million.

- Specialized Equipment: Chainsaws that cost $1,500 each, chippers that cost $80,000, and trucks that cost even more.

When Should You Actually Cut It?

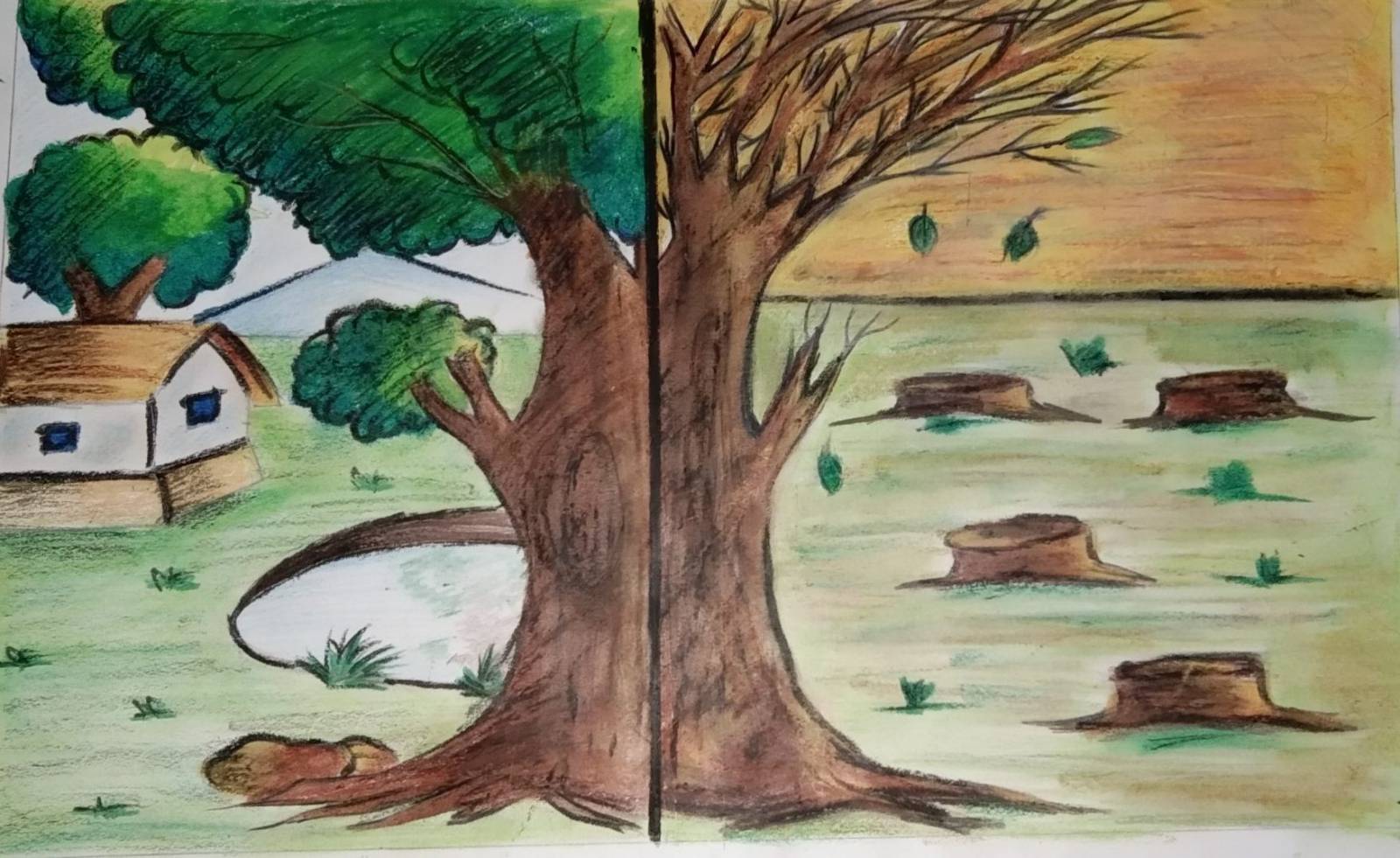

Not every big tree needs to go. I hate seeing healthy giants get chopped because someone is "worried about the leaves."

Trees provide massive cooling effects. They up your property value. They’re basically giant air filters. Before you kill a 100-year-old organism, get a "Level 2 Basic Assessment" from an ISA Certified Arborist. They can tell the difference between a scary-looking fungus and a terminal structural defect.

💡 You might also like: Why People That Died on Their Birthday Are More Common Than You Think

Sometimes, all a tree needs is "weight reduction" (pruning the ends of heavy limbs) or "cabling and bracing" (using high-strength steel cables to support weak crotches). It’s often cheaper than a full removal and keeps the tree alive for another fifty years.

Critical Safety Checklist for Homeowners

If you’re determined to do this yourself—which, honestly, I don't recommend for anything over 15 feet—you need to be obsessive about safety.

- Check for Lean: A tree leaning more than 15 degrees is a professional-only job. Period.

- Clear the Escape Path: You need two paths leading back and away at 45-degree angles from the direction of the fall. Not one. Two.

- Look Up: Every single time. Look for power lines and dead wood.

- The "Dutchman" Mistake: Don't let your back cut meet your notch cut perfectly. You need that hinge. If they meet, you lose all control.

- Personal Protective Equipment (PPE): Chainsaw chaps are not optional. They contain long fibers of Kevlar or ballistic nylon that clog the saw's drive sprocket instantly if you hit your leg. It’s the difference between a bruise and an amputation.

The Environmental Aftermath

When the tree is down, you’re left with a mountain of debris. A single large maple can produce five tons of wood and three tons of brush.

What happens to it?

Most of it gets chipped into mulch. The big logs might go to a sawmill if they’re high-quality species like Black Walnut or White Oak. But honestly? Most urban trees are full of "metal." Nails, old fence wire, even ceramic insulators from the 1940s. Sawmills hate urban wood because one hidden nail can ruin a $500 blade.

If you want to keep the wood for a fireplace, remember it needs to "season." Green wood is mostly water. If you burn it now, you’ll just get a lot of smoke and creosote buildup in your chimney. It needs at least a year under a tarp to be useful.

Actionable Steps for Your Property

If you have a massive tree and you're sweating every time the wind picks up, do this:

- Find the Credentials: Go to the ISA (International Society of Arboriculture) website and use their "Find an Arborist" tool. Don't just hire the guy who knocked on your door with a flyer.

- Get Three Quotes: Prices vary wildly based on how much work a crew has scheduled.

- Ask About the Stump: Removal usually doesn't include "stump grinding" unless specified. If you don't pay for it, you'll have a rotting hunk of wood in your yard for the next twenty years.

- Verify Insurance: Ask for a Certificate of Insurance (COI) sent directly from their agent to you. People fake these with Photoshop all the time.

- Permit Check: Many cities (like Atlanta or Seattle) have strict "Tree Protection Ordinances." You might need a permit just to cut down a tree on your own land. If you do it illegally, the fines can be tens of thousands of dollars.

Managing big timber is a heavy responsibility. It’s part engineering, part biology, and a lot of respect for the sheer power of nature. Take it seriously.

Always look up. Stay out of the "drop zone." And if your gut tells you a job is too big, it probably is. There’s no shame in calling the guys with the cranes. It’s a lot cheaper than a new roof.