It is still up there. Right now, as you read this, a machine the size of a small SUV is crunching across a landscape of frozen dust and iron oxide, clicking its shutters. We have become so used to seeing curiosity rover pictures from mars on our social media feeds that we’ve almost lost the plot. It’s easy to scroll past a grainy, orange-tinted landscape and think, "Oh, more rocks." But if you actually stop and look—really look—at the raw data coming back from Gale Crater, you realize that these aren't just photos. They are a time machine.

Gale Crater is a 96-mile-wide scar on the Martian surface. It’s old. Like, 3.5 to 3.8 billion years old. When Curiosity landed there in August 2012, the goal wasn't just to take pretty pictures for desktop wallpapers. The goal was to find out if Mars was ever "habitable." That’s a fancy way of asking if a microbe could have survived there without immediately dying. The pictures are the primary evidence.

The sheer volume of visual data is staggering. Since landing, Curiosity has sent back hundreds of thousands of images. Some are wide-angle panoramas that make you feel like you’re standing in the middle of a desert in Arizona, while others are microscopic views of mineral veins that look like something out of a jewelry store. But there is a massive disconnect between what the rover sees and what we see on our screens.

Why some curiosity rover pictures from mars look "fake" to the untrained eye

You've probably seen those ultra-vivid, blue-sky photos of Mars and wondered if NASA is just messing with us. They aren't. But they aren't showing you "true color" either, at least not always.

Mars is dusty. The atmosphere is thin—about 1% of Earth's—and it's filled with suspended particulates that scatter light in weird ways. When the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) processes these images, they often use a technique called "white balancing." This basically adjusts the lighting so the rocks look like they would if they were under Earth's sun. Why? Because geologists need to recognize the minerals. If everything is bathed in a muddy butterscotch glow, it's hard to tell the difference between sedimentary rock and volcanic basalt.

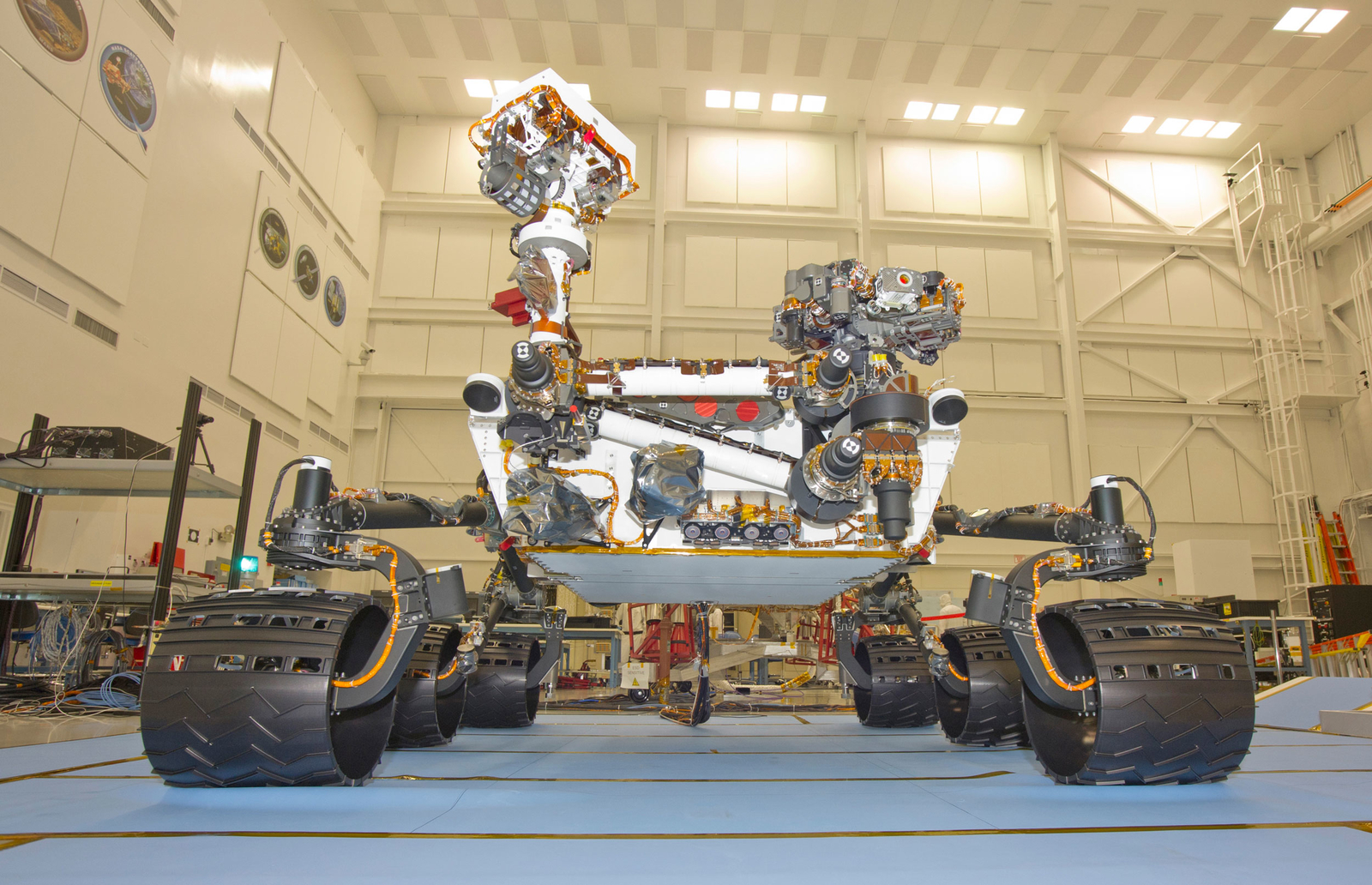

Then there are the "selfies." You’ve seen them. Curiosity looks like it’s being photographed by a floating friend. There is no floating friend. The rover uses its Mars Hand Lens Imager (MAHLI), located on the end of its robotic arm. By taking dozens of shots and stitching them together, the team can edit out the arm itself. It’s basically the most expensive Instagram filter in history.

Sometimes the pictures show things that shouldn't be there. Or so the internet thinks. We’ve had the "Mars Rat," the "Doorway," and even a "Humanoid Figure." This is just pareidolia—our brains trying to make sense of random shapes. When you look at enough curiosity rover pictures from mars, you’re bound to see a rock that looks like a Chihuahua eventually.

The grit and the gears: A decade of mechanical wear

If you want to see the real story of the mission, don't look at the mountains. Look at the wheels.

In 2014, engineers noticed something alarming in the images sent back by the rover's MAHLI camera. The solid aluminum wheels were developing holes. Big ones. The Martian terrain in Gale Crater turned out to be much sharper and "pointier" than anyone anticipated. These ventifacts—rocks carved into blades by eons of wind—were literally chewing through the rover's skin.

This was a pivot point for the mission.

NASA started taking regular "health check" photos of the undercarriage. If you look at the sequence of wheel photos from 2013 to 2026, it’s a grueling visual record of survival. They had to change how they drove. They started picking paths through softer sand to save the remaining metal. They even updated the rover's software to adjust the speed of the wheels individually, reducing the "drag" that was causing the punctures. It’s a testament to human ingenuity that the thing is still rolling.

Honestly, the "boring" pictures are often the most important. Curiosity spends a lot of time looking at its own feet. It looks at the drill bits. It looks at the dust buildup on its deck. This isn't vanity; it’s maintenance. When you’re 140 million miles away from the nearest mechanic, you take a lot of photos of your own lug nuts.

The discovery of Mount Sharp and the ancient lakes

Curiosity’s primary target has always been Mount Sharp (Aeolis Mons), a 3-mile-high mountain rising from the center of the crater. The rover has been "climbing" this mountain for years.

Each layer of rock Curiosity photographs as it ascends is a page in a history book. The lower layers are made of clays and minerals that only form in the presence of liquid water. Not just a little water—persistent, long-term lakes. The curiosity rover pictures from mars showing "cross-bedding" in the sandstone are the smoking gun. These are the same patterns you see in riverbeds on Earth where water once flowed over sand in ripples.

As the rover climbs higher, the geology changes. The rocks become more sulfate-rich. This suggests a drying-out period. We are literally watching a planet die through the eyes of a robot. We see the transition from a wet, potentially life-supporting world to the frigid desert we see today.

Beyond the visual: ChemCam and the laser zaps

Curiosity doesn't just "see" in the traditional sense. It has a laser.

The ChemCam instrument sits on the rover’s "head" (the mast). It can fire a laser at a rock up to 23 feet away. This vaporizes a tiny speck of the rock into a glowing plasma. The rover then takes a picture of that plasma through a spectrometer to see what elements are inside.

When you see a photo of a Martian rock with a perfectly straight line of five small pits, you’re looking at a crime scene. Curiosity was there. It zapped that rock. It knows exactly how much magnesium, iron, and silica is in it.

The Mastcam-Z and other sensors also capture multispectral images. These aren't for humans. They capture wavelengths of light that we can't see, highlighting specific minerals like hematite. To us, it might look like a dusty hill. To a scientist looking at the multispectral data, it looks like a neon sign pointing toward an ancient shoreline.

The weirdness of Martian weather

Mars is a dynamic world. It's not a static graveyard. One of the most haunting sets of images Curiosity ever captured was of "dust devils" dancing across the crater floor. These are towering whirlwinds that suck up the fine Martian soil.

Then there are the clouds. Martian clouds are rare because the air is so dry, but Curiosity has photographed "noctilucent" or night-shining clouds. These form at very high altitudes where it’s so cold that water ice or carbon dioxide ice crystallizes. They shimmer with an iridescent, mother-of-pearl quality.

And don't forget the sunsets. On Earth, the sky is blue and the sunset is red. On Mars, because of the way the dust scatters light, the sky is reddish during the day and the sunset is blue. Seeing a blue sun sink below a jagged Martian horizon is probably the most "alien" thing you will ever witness. It defies our biological expectations of how a sky should behave.

Navigating the raw image archives

If you want the real experience, stay away from the "curated" galleries for a minute. NASA maintains a public archive of every single raw image Curiosity sends back. They aren't cleaned up. They aren't color-corrected. Many are in black and white because they come from the "Navcams" used for driving.

When you look at the raw feed, you see the "blooper reel." You see blurry shots where the rover was moving. You see images filled with "noise" from cosmic rays hitting the sensor. You see the repetitive, systematic way the robot "eyes" its surroundings. It’s lonely. It’s methodical. It’s beautiful in a very stark, industrial way.

👉 See also: How Do I Unlock My Android Phone: What Most People Get Wrong

The community of amateur image processors—people like Kevin Gill or Seán Doran—take this raw data and turn it into masterpieces. They stitch together thousands of frames to create 360-degree VR experiences. They aren't NASA employees; they’re just fans with high-end computers and a lot of patience. This democratization of space exploration is something we’ve never had before.

What these pictures mean for the future

Curiosity is the scout. Everything it sees informs the missions that follow. The Perseverance rover, currently in Jezero Crater, is there because Curiosity proved that Mars was once "habitable." Curiosity found the organic molecules. It found the drinkable water (well, it was drinkable three billion years ago).

The pictures are also our best way of preparing for human boots on the ground. We need to know how the dust sticks to solar panels. We need to know how the radiation degrades camera sensors over time. We need to know if the "soil" (regolith) is toxic (spoiler: it contains perchlorates, which aren't great for humans).

Every time Curiosity clicks its shutter, it’s reducing the risk for the first person who will eventually stand in that dust.

How to use this information today

If you’re a hobbyist or just a curious person, don't just look at the headlines. The best way to engage with these images is to go straight to the source.

- Visit the NASA JPL Raw Image Gallery: You can filter by "Sol" (Martian day). Check what the rover did yesterday. It’s the closest thing we have to a live feed from another planet.

- Look for the "Scale Bars": Often, NASA will include a small "penny" or a calibration target in the photos. Use these to understand the size. A rock that looks like a mountain might only be three inches tall.

- Check the "Exif" data: Many processed images include info on which camera was used. The MAHLI is for close-ups; the Mastcams are for the big views.

- Follow the weather reports: Curiosity has a weather station (REMS). Cross-reference the photos of dusty skies with the actual wind speed and pressure data. It makes the experience three-dimensional.

The mission won't last forever. The nuclear power source (the RTG) is slowly decaying. Eventually, Curiosity will stop moving. It will become a monument. But until then, it’s our eyes on a world that was once very much like our own.

Keep looking at the rocks. Sometimes, a rock isn't just a rock; it's a piece of a puzzle that explains how planets live and die.

Next Steps for Enthusiasts

To get the most out of your exploration, head over to the NASA Mars Exploration Program website and look for the "Multimedia" section. Specifically, seek out the 360-degree panoramas. If you have a VR headset or even just a smartphone, you can "stand" on the surface of Gale Crater. Seeing the scale of the "Haualand" ridges or the "Marker Band" valley in a spherical format provides a sense of depth that a flat 2D image simply cannot match. Additionally, you can download the raw image datasets if you are interested in trying your hand at your own color-correction or stitching—many of the most famous images of the rover were actually produced by enthusiasts in their spare time using this exact data.