Nigeria is loud. If you’ve ever stepped foot in a Lagos market or sat through a Yoruba wedding, you know exactly what I mean. But beneath the surface-level noise of 200 million people living on top of each other, there is a rhythm. Cultural traditions in nigeria aren't just things people do because their grandfathers did them; they are the actual glue holding a very fragile, very complex country together.

Most outsiders see the "Big Three"—the Hausa, Igbo, and Yoruba. Honestly, that’s a lazy way to look at it. There are over 250 ethnic groups here. Each one has its own specific way of handling birth, death, and everything messy in between. You can't just lump them together.

The Kola Nut: More Than Just a Snack

If you visit an Igbo home in the southeast and they don't offer you a kola nut, something is wrong. Seriously. It’s not about the caffeine kick, even though those things are bitter as hell and will keep you awake for days.

The kola nut is a spiritual gatekeeper. There’s a popular saying: "He who brings kola brings life." In Igbo culture, the breaking of the nut involves a whole ritual. Usually, the oldest man in the room has to do the honors. He prays, blesses the nut, and then it’s shared. It’s a contract. Once you eat that nut with someone, you’ve basically sworn you won’t harm them. It’s a peace treaty in a tiny, purple shell.

But here’s where it gets nuanced. In some parts of Igboland, women aren't allowed to break the kola nut. Some people think this is outdated, and there’s a lot of debate in modern circles about whether these cultural traditions in nigeria should evolve. Yet, for the traditionalists, it’s about maintaining a specific cosmic order.

Why the Yoruba "Aso Ebi" is a Financial Stress Test

You’ve probably seen the photos. Rows of people dressed in identical, eye-watering lace or Ankara fabrics. That’s Aso Ebi, which literally translates to "family cloth."

It’s beautiful. It’s vibrant. It’s also a massive social pressure cooker.

When someone has a wedding or a funeral, they pick a specific fabric. If you’re a friend, you’re expected to buy it. It shows solidarity. But let’s be real—sometimes that lace costs more than a month’s rent in Ibadan. People go into debt just to fit in. Why? Because in Yoruba culture, showing up is everything. If you don't wear the Aso Ebi, you’re basically saying you don’t value the relationship. It’s a visual tally of your social capital.

💡 You might also like: Why Every Mom and Daughter Photo You Take Actually Matters

I spoke to a textile vendor in Balogun Market last year. She told me that during the "Ember" months (September to December), she sells enough lace to cover a small village. This isn't just fashion; it’s an informal economy worth billions of Naira.

The Calabar Fattening Room: A Misunderstood Rite

Down south in Cross River and Akwa Ibom, the Efik people have something called the Nkuho. People usually call it the "Fattening Room."

Western media loves to freak out about this. They paint it as this weird, oppressive practice where girls are forced to eat. But if you talk to Efik elders, they see it differently. Historically, it was a finishing school. A young woman would be secluded, fed well, and taught the "art of womanhood." This included everything from childcare to traditional dance and how to manage a household.

- Seclusion from the public eye.

- Learning the Ekombi dance.

- Receiving advice from older matriarchs.

- Skincare treatments using natural herbs and oils.

In a world that prizes thinness, the Efik traditionally prized "fullness" as a sign of health, wealth, and fertility. Today, the practice is fading. Most modern Efik women do a "lite" version for a few days before their wedding instead of months. It’s a compromise between the fast-paced modern world and a deep-rooted history.

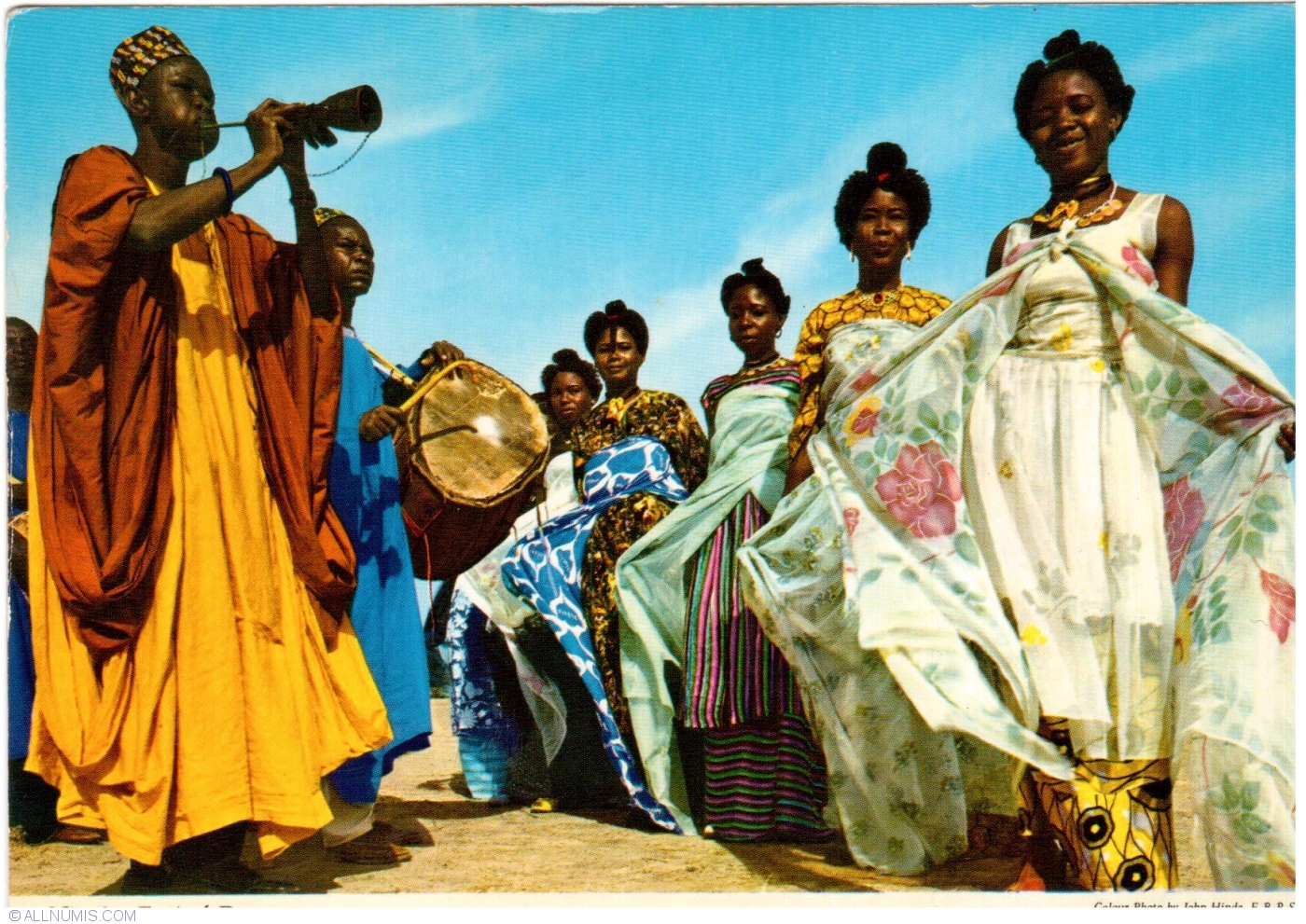

The Durbar Festival: Northern Royalty on Horseback

Northern Nigeria is different. It’s drier, quieter (mostly), and deeply Islamic. But once a year, during Eid al-Fitr and Eid al-Kabir, things get wild. This is the Durbar.

Imagine thousands of men in turbans, riding decorated horses, charging at full speed toward the Emir. At the last second, they veer off and salute. It’s a display of military might that dates back hundreds of years to when the Hausa-Fulani caliphates were at their peak.

The colors are insane. You’ve got the Yan Kwarami (musketeers) firing shots into the air and the Jester figures keeping the crowd entertained. It’s a sensory overload. But the heart of it is the Jahi—that final horse charge. It’s an oath of loyalty. Even in 2026, the Emirs of Kano, Zaria, and Katsina hold immense cultural power, even if they don't have formal political "teeth" anymore.

📖 Related: Sport watch water resist explained: why 50 meters doesn't mean you can dive

Respect is a Currency

In Nigeria, age is everything. You don't call someone older than you by their first name. That’s a fast track to getting a lecture or a "disgusted" look. You use "Uncle," "Auntie," "Brother," or "Sister," even if you aren't related.

Among the Yoruba, young men prostrate—they literally lie flat on the ground—to greet elders. Girls kneel. To a Westerner, it might look like subservience. To a Nigerian, it’s just manners. It’s about acknowledging that the person standing in front of you has seen more of life than you have.

What People Get Wrong: It’s Not Static

The biggest mistake people make is thinking cultural traditions in nigeria are stuck in the 1800s. They aren't. They’re constantly morphing.

Look at "Traditional Weddings." Most Nigerians today do two or even three ceremonies. They do the "Traditional" (the introduction, the dowry, the cultural rites) and then the "White Wedding" (the church or registry ceremony). It’s an expensive, exhausting double-header. But it’s necessary because, in the Nigerian mind, you aren't married until both the ancestors and the law are satisfied.

There's also the "Nollywood Effect." Movies have exported Nigerian culture across Africa. Now, you see people in Kenya or South Africa using Nigerian slang or trying to replicate the "Owanbe" party style. Nigeria has become a cultural superpower, not through its government, but through its sheer creative will.

The Darker Side: Traditions Under Fire

We have to be honest. Not every tradition is celebrated. There is a massive internal struggle regarding things like the Osu caste system in parts of Igboland, where some people are still treated as outcasts based on ancestral lineage.

Then there’s the issue of female genital mutilation (FGM). While it’s been outlawed and is rapidly declining due to intense advocacy from groups like the Girl Generation, it’s a grim part of the historical landscape that many Nigerians are fighting to bury forever.

👉 See also: Pink White Nail Studio Secrets and Why Your Manicure Isn't Lasting

How to Navigate Nigerian Culture as an Outsider

If you’re traveling to Nigeria or working with Nigerians, you don't need to be an expert. You just need to be humble. Nigerians are generally very forgiving of "JJCs" (Johnny Just Come—newcomers) as long as you show respect.

- Never use your left hand. Don't give a gift, take a change, or eat with your left hand. It’s considered "unclean" in many regions.

- Accept the food. Even if it’s too spicy, try a bit. Rejecting food is like rejecting the person.

- Dress the part. If you're invited to an event and told there’s a color code, try to match it. People will love you for it.

- Ask before you film. Some festivals are deeply spiritual and photography might be restricted.

The reality is that cultural traditions in nigeria are a mess of contradictions. They are expensive, time-consuming, and sometimes frustrating. But they are also the reason why, despite the economic hurdles and political drama, the country has a soul that refuses to be quieted.

Practical Next Steps for the Culturally Curious

If you want to experience this firsthand without just reading about it, start with the food. Go find a local spot that serves Pounded Yam and Egusi soup. Eat with your (right) hand.

Research the Osun-Osogbo Sacred Grove. It’s a UNESCO World Heritage site and one of the last places where you can see Yoruba traditional religion in its original setting. It’s hauntingly beautiful and tells a story of Nigeria that goes far beyond the skyscrapers of Lagos.

Finally, keep an eye on the calendar. If you can time a trip to coincide with the Argungu Fishing Festival in Kebbi or the New Yam Festival in the east, do it. You’ll see a side of the human experience that hasn't been sterilized by globalization.

- Buy a book by Chinua Achebe (start with Things Fall Apart for the Igbo perspective).

- Watch a documentary on the Benin Bronzes and their ongoing repatriation.

- Listen to Fela Kuti’s lyrics—he was a master at critiquing the erosion of traditional values.

Nigeria isn't a place you observe. It’s a place you feel. The traditions aren't museum pieces; they are living, breathing, and occasionally shouting.