Thirteen days. That was the window where the world almost turned into a radioactive cinder in October 1962. Most of us have seen the grainy black-and-white shots of John F. Kennedy looking stressed or those low-altitude flyover snaps of missile sites in the Cuban jungle. But honestly, Cuban missile crisis pictures aren't just artifacts; they were the actual ammunition of the Cold War. Without those specific rolls of film, the 20th century ends very differently.

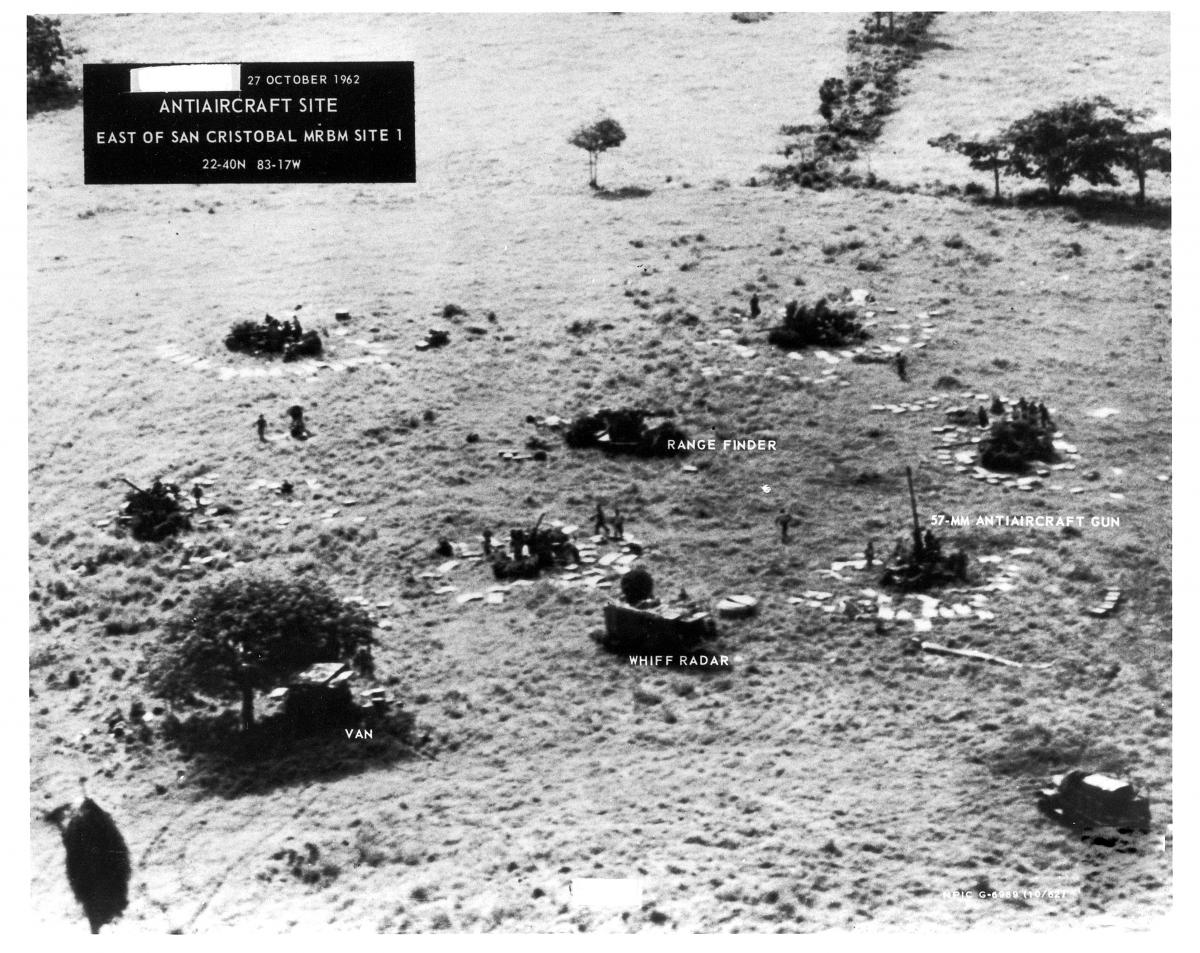

It started with a U-2 flight. Major Richard Heyser was the pilot. He was flying so high he could see the curvature of the Earth, snapping frame after frame of the San Cristobal region. When the film was processed at the National Photographic Interpretation Center (NPIC), the analysts didn't just see trees. They saw shadows. Specifically, they saw the shadows cast by Soviet R-12 intermediate-range ballistic missiles.

The Grainy Proof That Changed Everything

Imagine being Dino Brugioni. He was one of the lead analysts at the NPIC. He’s looking at a magnifying glass, staring at "scratches" on a piece of film, and realizing those scratches are nuclear tips aimed at Washington D.C. This is the raw power of Cuban missile crisis pictures. They weren't just "news photos." They were actionable intelligence.

People often think the CIA just showed JFK a photo and he got mad. It wasn't that simple. The early images were incredibly hard to read if you weren't a pro. You're looking at mud, some trucks, and some tents. But the analysts noticed "trailers" that were too long for standard Cuban military use. They noticed "ox-cart" patterns in the dirt that suggested heavy equipment being moved into position.

The Soviet Union thought they were being sneaky. Nikita Khrushchev basically bet the house on the idea that the U.S. wouldn't fly high enough or often enough to catch them before the missiles were operational. He was wrong.

Why Quality Mattered More Than Quantity

During the height of the tension, the U.S. Navy and Air Force started flying "Blue Moon" missions. These were low-level, high-speed reconnaissance runs. Pilots like William Ecker flew RF-8A Crusaders just a few hundred feet above the treetops.

📖 Related: Weather Forecast Lockport NY: Why Today’s Snow Isn’t Just Hype

The cameras were roaring.

These guys were coming back with pictures so clear you could see the expressions on the faces of the Soviet technicians. You could see the serial numbers on the crates. This wasn't just "surveillance." It was a psychological gut punch. When Adlai Stevenson finally showed these Cuban missile crisis pictures at the United Nations, it was a "mic drop" moment before that term existed. He told the Soviet Ambassador Zorin he was prepared to wait for an answer "until hell freezes over," and then he brought out the boards.

The world went silent.

The Photos the Public Didn't See Until Later

We usually focus on the aerial stuff. But there’s a whole other side to the visual history of 1962. It’s the "civilian" side. Think about the photos of families in Florida building fallout shelters in their backyards. Or the shots of kids in New York City practicing "duck and cover" drills under wooden desks as if that would do anything against a multi-megaton blast.

There's a specific shot of a grocery store in Miami. The shelves are empty. People weren't buying bread; they were buying canned peaches and bottled water. It shows the sheer, unadulterated panic that gripped the southern United States. If you look at these Cuban missile crisis pictures today, you can feel the humidity and the fear.

👉 See also: Economics Related News Articles: What the 2026 Headlines Actually Mean for Your Wallet

- The U-2 spy plane photos showed the hardware.

- The White House press photos showed the toll on the men in charge.

- The street-level photography showed a country that thought it was about to die.

One of the most famous shots is Kennedy from behind, leaning over a table in the Oval Office. He looks exhausted. It’s a quiet photo. No explosions. No missiles. Just a man who knows he might have to sign an order that kills 100 million people. That's the nuance of this era. The "big" pictures are of rockets, but the "important" pictures are of the human weight of the decision.

The Technical Magic of the 60s

It's easy to forget that this was all analog. There were no digital sensors. No instant uploads. A pilot had to fly over a hostile island, survive anti-aircraft fire (which Major Rudolf Anderson didn't—he was shot down and killed), land on a carrier or a base, and then the film had to be physically rushed to a lab.

The speed of the "kill chain"—from shutter click to the President's desk—was the only reason we didn't go to war. If the film took three days to process instead of hours, the missiles might have been fueled and ready to fire.

The Soviets had their own pictures, too. They had photos of the U.S. blockade—the "Quarantine"—from the decks of their freighters. These photos show U.S. destroyers cutting across the bows of Soviet ships. It was a game of chicken played with thousands of tons of steel.

How to Analyze Historical Photography Yourself

When you're looking at Cuban missile crisis pictures, you shouldn't just look at the center of the frame. Look at the edges. In the aerial shots of the missile sites, you can see the soccer fields. Why does that matter? Because Cubans didn't play soccer; they played baseball. Soviets played soccer. That was one of the "human" tells that confirmed it wasn't just a Cuban military buildup. It was a Soviet occupation.

✨ Don't miss: Why a Man Hits Girl for Bullying Incidents Go Viral and What They Reveal About Our Breaking Point

Look at the shadows. Analysts used the length of the shadows to calculate the height of the missiles. This allowed them to identify exactly which model of missile was being deployed—the SS-4 or the SS-5. The SS-5 could reach almost the entire continental U.S.

What Most People Get Wrong

A common misconception is that the crisis was over the second Khrushchev said he’d turn the ships around. It wasn't. The pictures taken after the deal was struck were just as vital. The U.S. demanded "visual verification." This meant Soviet ships had to uncover the missile canisters on their decks so U.S. planes could photograph them leaving.

The Soviets hated this. It was humiliating. But the U.S. wouldn't budge. "Show us the goods," was the vibe. So, there are these amazing photos of Soviet sailors standing on decks, looking up at American helicopters, with giant missile tubes exposed to the sky.

The Legacy of the Lens

The Cuban Missile Crisis was the first time in human history that photography was the primary deterrent to a total war. It proved that "seeing is believing" on a global, existential scale.

If you want to really understand the gravity of that October, don't just read the dry transcripts of the EXCOMM meetings. Look at the eyes of the people in the photos. Look at the way the Soviet soldiers in Cuba were trying to hide their equipment under palm fronds, failing miserably against the power of high-resolution optics.

To truly grasp the visual history of this event, you should seek out the declassified NPIC archives. Many of these Cuban missile crisis pictures are now available in high-resolution digital formats through the JFK Library or the National Archives.

Next Steps for Your Research:

- Visit the JFK Presidential Library's digital archives. They have the original "briefing boards" used to explain the situation to the President.

- Compare the U-2 shots with ground-level photos taken by Cuban citizens at the time. The contrast between what the "eye in the sky" saw and what people on the ground saw is jarring.

- Study the "Blue Moon" low-level recon photos. These are often more impressive than the high-altitude ones because they show the sheer proximity of the threat.

- Look for the "EXCOMM" candid photos. Photographer Cecil Stoughton captured the internal tension of the White House in a way that formal portraits never could.