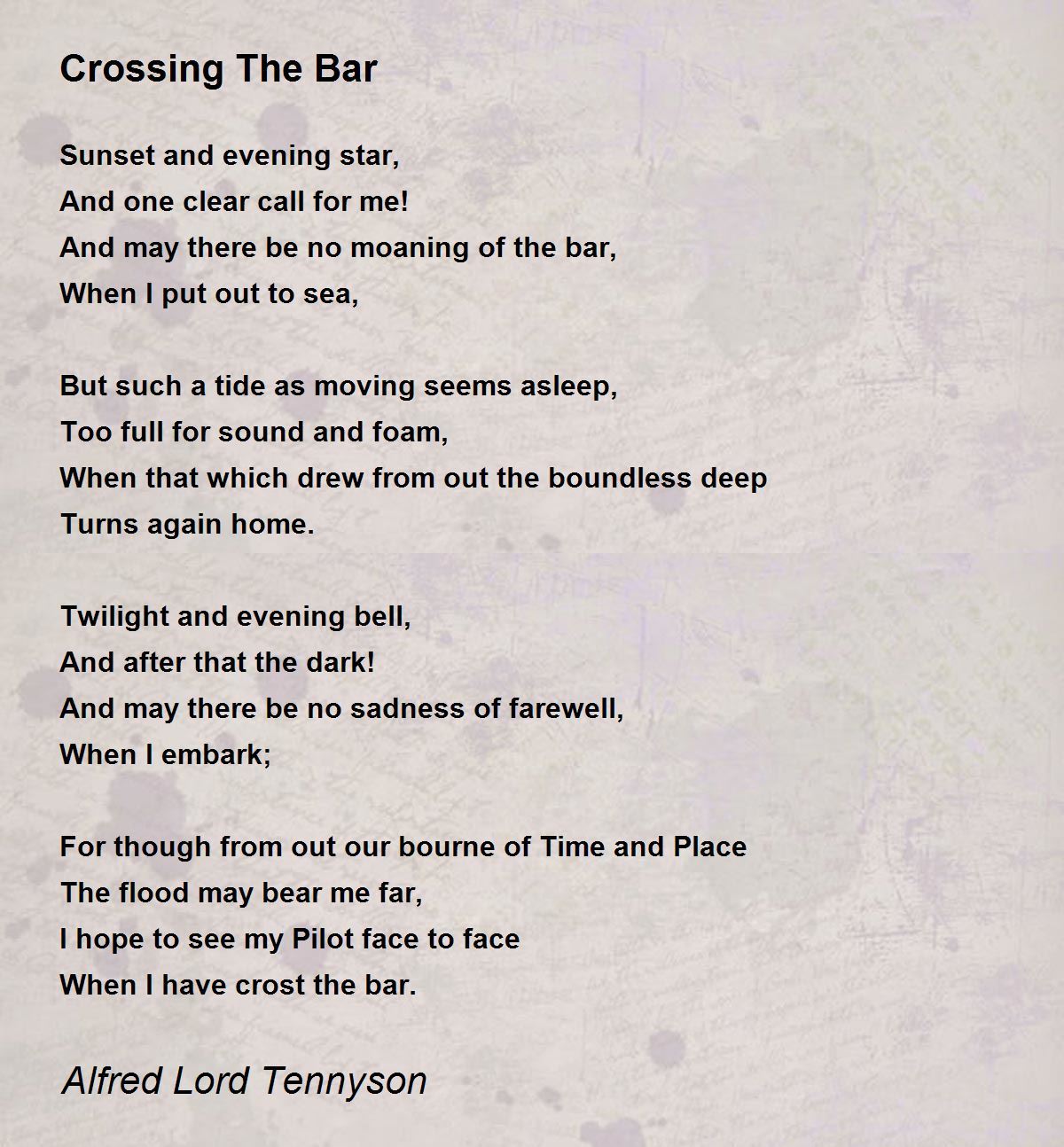

Alfred Lord Tennyson was 80 years old when he wrote it. He was on a ferry, crossing the Solent—the stretch of water between the Isle of Wight and mainland England—heading toward his home at Farringford. He’d been sick. Death wasn’t a theoretical concept anymore; it was a passenger on the boat. In just twenty minutes, he scribbled down the crossing the bar poem, and it became the most famous goodbye in English literature.

It’s weirdly simple.

Most people think of Victorian poetry as this dense, impenetrable thicket of "thees" and "thous" that requires a PhD to untangle. But Tennyson didn’t do that here. He used words that a child could understand to describe a transition that terrifies the bravest adults. He was the Poet Laureate, the rockstar of his era, yet he spent his final years obsessed with the mechanics of the soul’s departure.

The Literal Meaning of the "Bar"

So, what’s the "bar" actually?

In nautical terms, a sandbar is a ridge of sand built up by tides at the entrance to a harbor. It’s the boundary between the safe, shallow water of the port and the deep, unpredictable wildness of the open ocean. Crossing it is tricky. If the tide isn't right, you’ll ground your ship. If the waves are too choppy, you'll capsize.

Tennyson uses this physical barrier as a metaphor for the moment of death. He isn't just "dying"; he’s embarking. He’s leaving the "shore" of human life and heading into the "boundless deep." Honestly, it’s a much more badass way to look at the end of life than just "fading away."

He specifically requested that this poem be placed at the very end of every collection of his work published after his death. He wanted it to be his final word. His son, Hallam Tennyson, noted that his father wrote the verses in a moment of "spiritual clarity" that stayed with him until he passed away in 1892.

Why the Rhythm Feels Like the Ocean

If you read the crossing the bar poem out loud, you’ll notice something. It breathes.

The lines fluctuate in length. Some are long and sweeping, like a heavy swell at sea. Others are short and punchy. "And one clear call for me!" That's a sharp, staccato burst. It mimics the actual movement of water. Tennyson was a master of "onomatopoeia of rhythm," a fancy way of saying he made the poem sound like the thing it was describing.

💡 You might also like: Virgo Love Horoscope for Today and Tomorrow: Why You Need to Stop Fixing People

Breaking Down the Stanzas

The first stanza sets the scene: sunset and the evening star. It’s the end of the day, which obviously represents the end of a long life. He hears a "call." It’s not a scary call; it’s just clear. He’s ready.

Then, in the second stanza, he talks about a tide that seems "asleep." He wants a death that isn't full of "foam and bellies," which basically means he’s hoping for a peaceful transition. He doesn't want a struggle. He wants a tide that is so full it doesn't even make a sound as it carries him back home to the "boundless deep."

"But such a tide as moving seems asleep,

Too full for sound and foam,

When that which drew from out the boundless deep

Turns again home."

It’s interesting how he views life as being "drawn out" of the deep. To Tennyson, being alive was the temporary state. The ocean—the afterlife, the void, whatever you want to call it—was the "home" he was returning to.

The Pilot Face to Face

The most famous—and controversial—part of the poem is the final stanza. Tennyson writes:

"I hope to see my Pilot face to face / When I have crost the bar."

Who is the Pilot?

Literally, a harbor pilot is someone who knows the local waters and hops onto a ship to help guide it safely across the dangerous sandbar. Metaphorically, most readers assume he means God. But Tennyson was always a bit more nuanced (and sometimes more skeptical) than your average Victorian church-goer.

📖 Related: Lo que nadie te dice sobre la moda verano 2025 mujer y por qué tu armario va a cambiar por completo

He didn't say he would see the Pilot. He said he hoped to.

According to Hallam Tennyson's memoirs, the poet explained the Pilot as "that Divine and Unseen who is always guiding us." It’s a subtle distinction. He’s not describing a bearded man in the clouds. He’s describing a force that has been on the ship the whole time, even if the passenger didn't realize it until the journey was over.

Common Misconceptions About the Poem

People get things wrong about this poem all the time.

First, people think it’s a sad poem. It really isn't. It’s actually quite defiant and calm. There’s no "mourning of the bar" allowed. He explicitly forbids people from crying for him.

Second, there's a weird myth that he wrote it on his deathbed. He didn't. He wrote it three years before he died. He had plenty of time to edit it, but he barely changed a word from the original draft. It came out whole.

Third, people often confuse "The Bar" with the "River Styx" from Greek mythology. While there are similarities—crossing water to reach the afterlife—Tennyson’s imagery is purely nautical and British. He’s thinking of the English Channel, not a mythical underworld.

Why We Still Care in 2026

We live in a world that is terrified of aging and death. We try to bio-hack our way into immortality. We use filters to hide the "sunset" of our faces.

The crossing the bar poem hits different because it accepts the inevitable with such extreme grace. It’s the ultimate "vibe check" for the end of life. Tennyson isn't fighting the tide. He’s riding it.

👉 See also: Free Women Looking for Older Men: What Most People Get Wrong About Age-Gap Dating

In a time when everything is digitized and temporary, there’s something grounding about a poem that deals in the permanent elements: the stars, the tide, the evening bell, and the deep sea. It’s a reminder that even the greatest "rockstar" poets eventually have to put down the pen and step onto the boat.

Applying Tennyson’s Stoicism Today

You don't have to be religious to get something out of this. You can view the "Pilot" as your own intuition, your legacy, or just the natural order of the universe.

- Embrace the transition: Stop fighting things you can't control. Whether it’s a job change, a breakup, or a move, treat it like "crossing the bar"—a necessary movement toward something bigger.

- Silence the noise: Tennyson wanted "no moaning." Sometimes, the best way to handle a big life change is with quiet dignity rather than a loud social media post.

- Look for the "clear call": Pay attention to the signs that it's time to move on to the next chapter. Don't linger in the harbor when the tide is calling you out.

Practical Steps for Reading and Sharing

If you're looking to dive deeper into Tennyson or want to use this poem for a memorial or a personal reflection, here is how to handle it:

1. Read it at sunset. It sounds cheesy, but the poem is literally set at dusk. Seeing the light fade while reading about the "evening star" makes the metaphors click in a way a computer screen can't.

2. Listen to a choral arrangement. Because of its rhythmic beauty, the crossing the bar poem has been set to music by dozens of composers, including Sir Hubert Parry. Hearing it sung captures the "too full for sound" quality Tennyson was aiming for.

3. Contrast it with "Ulysses." If you want to see Tennyson’s range, read "Ulysses" right after. That poem is about the struggle to keep living ("To strive, to seek, to find, and not to yield"). "Crossing the Bar" is the companion piece about the courage it takes to finally stop striving and let go.

4. Check the manuscript. If you're ever at the Lincoln Central Library in the UK, they house the Tennyson Research Centre. Seeing the actual handwriting—the shaky, 80-year-old script—makes the "clear call" feel a lot more personal and a lot less like a textbook assignment.

Tennyson eventually crossed his own bar on October 6, 1892. He died with a volume of Shakespeare in his hand, moonlight streaming into his room. He got the "clear call" he’d written about, and he went out exactly the way he hoped—without the moaning of the bar, just a quiet turn toward home.

Actionable Insight: Next time you're facing a major ending, read the poem aloud. Focus on the word "home" in the second stanza. It shifts the perspective of loss from a "departure" to a "return," which is a psychological hack for finding peace in the face of the unknown.