You're standing in a busy terminal at O'Hare. You look around and see a toddler throwing a tantrum, a teenager glued to a smartphone, a middle-aged businessman frantically checking his watch, and an elderly couple sharing a quiet sandwich. In that single, frozen moment, you’ve just performed a rough version of what social scientists do for a living. You’ve taken a snapshot of different age groups at one specific point in time to see how they differ. That’s the cross sectional study psychology definition in its simplest form. It’s a snapshot, not a movie.

Researchers love this method because it’s fast. Honestly, if you wanted to see how memory changes from age 20 to age 80 by following the same group of people, you’d be waiting sixty years to publish your paper. Nobody has that kind of time, and certainly, no one has that kind of grant money. Instead, psychologists use a cross-sectional design to look at people of different ages right now, today, all at once. It’s efficient, but it’s got some quirks that can absolutely wreck your data if you aren’t careful.

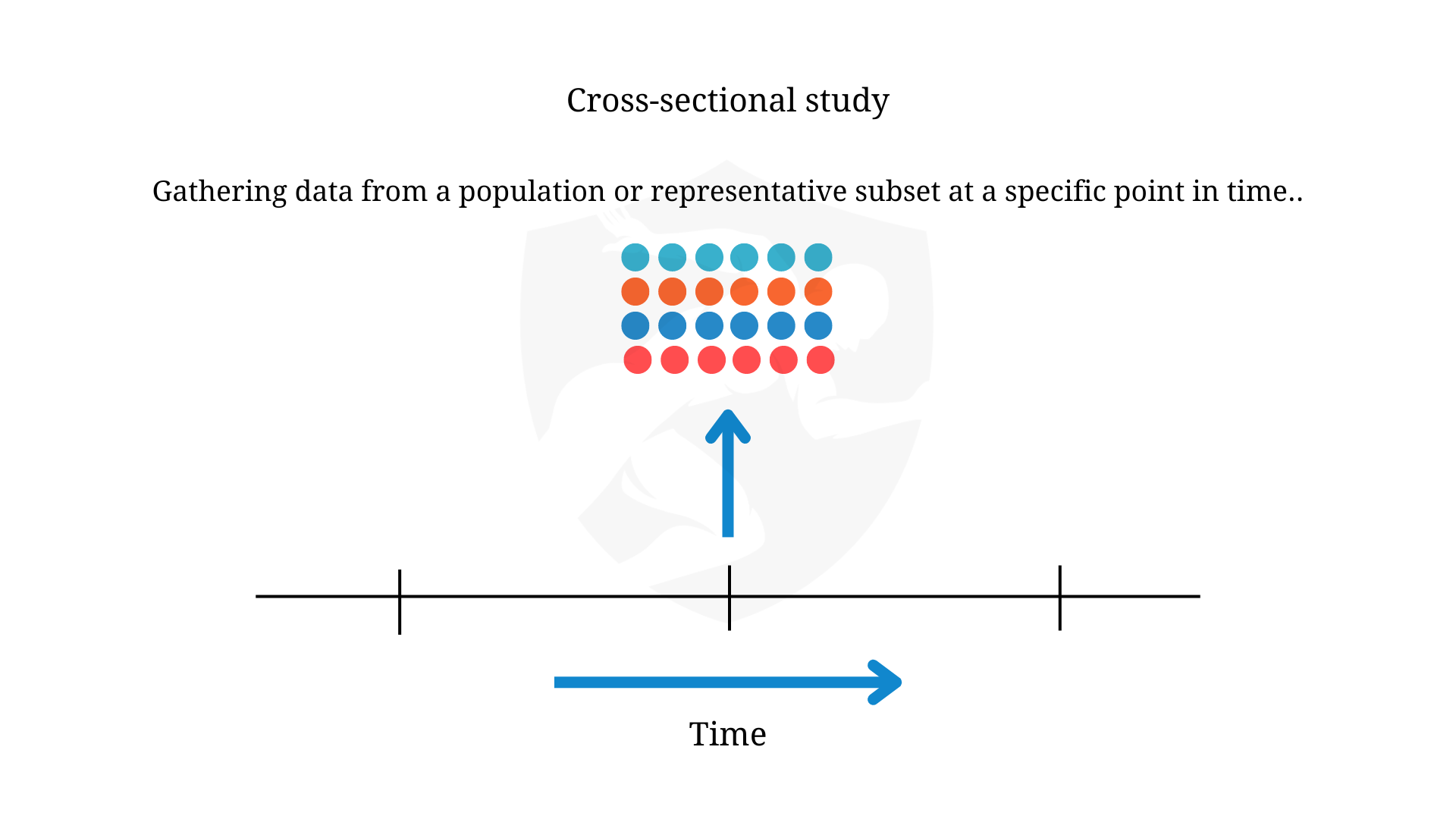

What a Cross Sectional Study Actually Is

In the world of psychological research, a cross-sectional study is an observational strategy. You aren't manipulating variables in a lab. You’re looking at "cohorts"—groups of people who share a defining characteristic, usually their age.

Think about a researcher studying digital literacy. They might recruit 50 people in their 20s, 50 in their 40s, and 50 in their 60s. They give everyone the same test on the same day. By comparing the scores, the researcher tries to figure out how age relates to tech skills. It's a "between-subjects" design. You aren't looking at how John changed over time; you're looking at how John (age 20) differs from Mary (age 60).

Why the "Snapshot" Matters

The defining feature here is the lack of a timeline. In a longitudinal study, you're the director of a long-running documentary. In a cross-sectional study, you're a street photographer. This matters because it limits what you can actually claim. You can find correlations—links between variables—but you can’t prove that one thing caused another over time. You just know that, currently, Group A looks different than Group B.

The Cohort Effect: The Great Data Killer

If you’re diving into the cross sectional study psychology definition, you have to talk about the cohort effect. This is the "hidden boss" of research flaws.

A cohort effect happens when the results of your study aren't actually caused by age, but by the era the person grew up in. Let's go back to that digital literacy test. If the 60-year-olds score lower than the 20-year-olds, is it because their brains are aging? Or is it because they grew up with rotary phones and physical encyclopedias while the 20-year-olds had iPads in their cribs?

The Great Intelligence Debate

This isn't just academic nitpicking. It caused a massive stir in IQ research decades ago. Early cross-sectional studies suggested that human intelligence peaked in the late teens and then plummeted. People panicked. It looked like we all got significantly "dimmer" after age 25.

But when researchers like K. Warner Schaie started the Seattle Longitudinal Study, they found something different. By following the same people over decades, they realized intelligence is actually quite stable until much later in life. The earlier cross-sectional studies were skewed because older generations hadn't received the same level of formal education or nutrition as the younger ones. They weren't "losing" intelligence; they just started from a different baseline due to their historical context.

Advantages: Why We Use It Anyway

Despite the flaws, cross-sectional research is the backbone of public health and developmental psychology.

- It’s incredibly cheap. You don't have to keep track of participants for years. You don't have to worry about "attrition," which is the fancy word for people moving away, losing interest, or passing away during a long study.

- Immediate results. If there’s a new mental health crisis or a sudden shift in social behavior, you can gather data in weeks. This was vital during the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic. Researchers needed to know right now how different age groups were coping with isolation.

- Hypothesis generation. These studies are great "scouts." They can find a weird correlation that suggests something interesting is happening. Once that link is found, then you spend the big money on a longitudinal study to prove it.

Real-World Examples in Psychology

Consider the work of developmental psychologists like Erik Erikson or Jean Piaget. While they used various methods, much of the foundational work in understanding "stages" of life comes from comparing different age groups.

In a modern context, look at developmental research on social media usage. A researcher might compare self-esteem levels in 13-year-olds, 17-year-olds, and 21-year-olds. If the 13-year-olds have significantly lower self-esteem and higher social media use, the researcher might suggest a link. Again, they can't say for sure that social media caused the low self-esteem as the kids aged, but they've found a starting point for further investigation.

Another area is "prevalence" studies. If the CDC wants to know how many people have depression in the United States, they do a cross-sectional survey. They take a massive sample of the population, ask them questions, and give us a percentage. It tells us the "load" of a condition on society at this exact moment.

How to Spot a Cross-Sectional Study in the Wild

When you're reading a news headline that says "Millennials are more stressed than Boomers," you're almost certainly looking at a cross-sectional study.

The tell-tale signs:

- The data was collected over a short window (e.g., "during the summer of 2024").

- They are comparing groups (Generations, income brackets, education levels).

- The conclusion is about differences, not changes over time.

Be wary of headlines that take this data and try to predict the future. If a study says "20-year-olds are more cynical than 60-year-olds," it does not necessarily mean that today's 20-year-olds will become less cynical as they age. They might just be a particularly cynical generation because of the specific world events they're living through.

Methodological Steps: How It's Done

If you were to design one of these yourself, the process is pretty straightforward, but you’ve got to be rigorous about your sampling.

🔗 Read more: How Many Litres of Water Should I Drink Per Day: The Truth Beyond the 8-Glass Myth

First, you define your population. Are you looking at all adults? Only college students? Then, you select your cohorts. These groups need to be as similar as possible in every way except for the variable you're studying (like age or smoking status).

Next comes the tool. Surveys, standardized tests, or physical exams. Because you're doing this all at once, you have to ensure the environment is consistent. If you test the morning group in a quiet room and the afternoon group in a noisy cafeteria, you’ve just introduced "confounding variables." Your data is now trash.

Finally, you run the stats. You're looking for the mean (average) differences between the groups. You use tests like an ANOVA (Analysis of Variance) to see if the differences are statistically significant or just random noise.

Limitations and Nuance

I've mentioned the cohort effect, but there’s also the issue of "selection bias." People who volunteer for studies are often different from those who don't. They might be more educated, have more free time, or be more interested in the topic. In cross-sectional designs, if your 70-year-old cohort consists only of ultra-healthy marathon runners because they’re the only ones who could make it to the lab, your data on "aging and physical health" is going to be wildly optimistic.

Also, you can't see the direction of a relationship. If a study finds that people who exercise more are also happier, does exercise make you happy? Or are happy people just more motivated to get off the couch? A cross-sectional snapshot can't tell you. It just says, "Hey, these two things are hanging out together."

Actionable Insights for Research Enthusiasts

When you're looking at the cross sectional study psychology definition for your own projects or just to be a more informed consumer of news, keep these steps in mind:

- Check the "N": That's the sample size. A cross-sectional study with 20 people is basically an anecdote. You want hundreds, if not thousands, for the data to mean anything.

- Question the Cohort: Ask yourself: "Could the era these people grew up in explain the results better than their age?"

- Look for Triangulation: Don't trust a cross-sectional study in isolation. Look for longitudinal studies or experimental data that back up the same claim. If all three methods point to the same conclusion, you're on solid ground.

- Identify the Sampling Method: Was it a "convenience sample" (like college students at the researcher's university) or a "representative sample" (a true cross-section of society)? The latter is much more valuable.

The cross-sectional method is a tool. It's a quick, dirty, and brilliant way to map out the landscape of human behavior. It’s the "first draft" of psychological science. It isn't perfect, and it doesn't give us the whole story, but without it, we'd be waiting decades to understand the world around us. Just remember that it shows you what is happening, but rarely tells you exactly why it started or where it’s going next.