History is messy. Usually, the stuff we learn in third grade is a polished, sanded-down version of a much gritier reality. When people think about the American Revolution, they see oil paintings of guys in powdered wigs signing parchment. But the spark didn't start in a quiet room with a quill pen. It started in the slush and mud of King Street on a freezing March night in 1770. And the first person killed in the Boston Massacre wasn't a colonial politician or a high-ranking officer. It was Crispus Attucks.

He died instantly. Two lead bullets to the chest.

Who was he, though? For a long time, textbooks sort of treated him like a footnote or a trivia answer. But if you actually look at the records from the 18th century, Attucks is a fascinating, complex figure who represented everything the British Crown was afraid of. He wasn't just some bystander who got unlucky. He was a sailor, a formerly enslaved man of African and Native American descent, and by all accounts, he was leading the charge that night.

The Chaos on King Street

March 5, 1770, was miserable. Boston was a pressure cooker. You had about 2,000 British soldiers occupying a town of only 16,000 people. Imagine that. Every time you go to the grocery store or the pub, there’s a guy with a bayonet watching you. Tensions were vibrating.

It started with a wigmaker’s apprentice yelling at a British officer about an unpaid bill. A lone sentry, Private Hugh White, stepped in to defend the officer and ended up striking the kid. That was the match in the powder keg. A crowd started gathering. People were shouting. Bells started ringing—which usually meant there was a fire—so even more people poured into the streets with buckets, only to find a standoff instead of flames.

By the time Crispus Attucks arrived with a group of sailors carrying large sticks, the vibe was past the point of no return.

The "massacre" wasn't some organized execution. It was a riot. The crowd was throwing snowballs, chunks of ice, and oyster shells. They were daring the soldiers to fire. Attucks was at the very front. According to witness testimony from the subsequent trials, he was leaning on a large cordwood stick. Some accounts say he even grabbed at a soldier’s bayonet. In that era, "the first person killed in the Boston Massacre" became a rallying cry, but in the moment, it was just pure, unadulterated chaos.

👉 See also: Casey Ramirez: The Small Town Benefactor Who Smuggled 400 Pounds of Cocaine

Why Crispus Attucks was a "Ghost" in the Records

Tracking down the life of Attucks before 1770 is tricky. Most historians, including those at the Massachusetts Historical Society, point to an advertisement in the Boston Gazette from 1750. It’s a runaway slave ad. It describes a "Mulatto fellow, about 27 Years of Age, named Crispus," who had run away from his owner, William Brown of Framingham.

He stayed missing for twenty years.

Think about the guts that took. He spent two decades living as a free man in a world that wanted to put him back in chains. He found work on whaling ships. This is why he was in Boston that night; sailors were notoriously anti-British because the Royal Navy kept "pressing" (kidnapping) American sailors into service.

Attucks had everything to lose by being there. If he got arrested, he could have been sent back to slavery. If he stayed quiet, he could have kept his freedom. He chose to stand his ground. When the British soldiers finally snapped and pulled their triggers, Attucks took the first hit. Samuel Gray and James Caldwell died shortly after. Samuel Maverick and Patrick Carr followed. But Attucks was the first.

The Trial and the John Adams Connection

Here is the part that usually blows people’s minds: John Adams defended the British soldiers. Yes, that John Adams. The future President.

Adams was a firm believer in the right to a fair trial, but his defense strategy was... uncomfortable. He didn't just argue self-defense; he leaned into the prejudices of the time. He described the crowd as a "motley rabble of saucy boys, negroes and molattoes, Irish teagues and outlish jack tarrs."

✨ Don't miss: Lake Nyos Cameroon 1986: What Really Happened During the Silent Killer’s Release

Specifically, he framed Attucks as the primary instigator. Adams told the jury that Attucks' "very looks was enough to terrify any person." He basically argued that the soldiers were right to be scared because a big, powerful man of color was leading a group of angry workers. It worked. Most of the soldiers were acquitted. Two were convicted of manslaughter and had their thumbs branded—a light sentence for five deaths.

The Shift from Victim to Hero

For about eighty years after the event, Attucks was largely ignored in the "official" history of the Revolution. Why? Because the narrative of the 1800s wanted to frame the Revolution as a white, intellectual movement.

It wasn't until the 1850s, when the abolitionist movement started picking up steam, that Attucks was "rediscovered." Black leaders like William Cooper Nell used the story of the first person killed in the Boston Massacre to prove a point: Black Americans had been there since the literal beginning. They had spilled blood for a country that still hadn't given them their rights.

In 1858, Boston held its first "Crispus Attucks Day." By 1888, a massive monument was erected on the Boston Common. It’s still there today. It’s a tall granite shaft topped with a figure representing Liberty, holding broken chains. At the base, Attucks' name is the first one you see.

What Most People Get Wrong

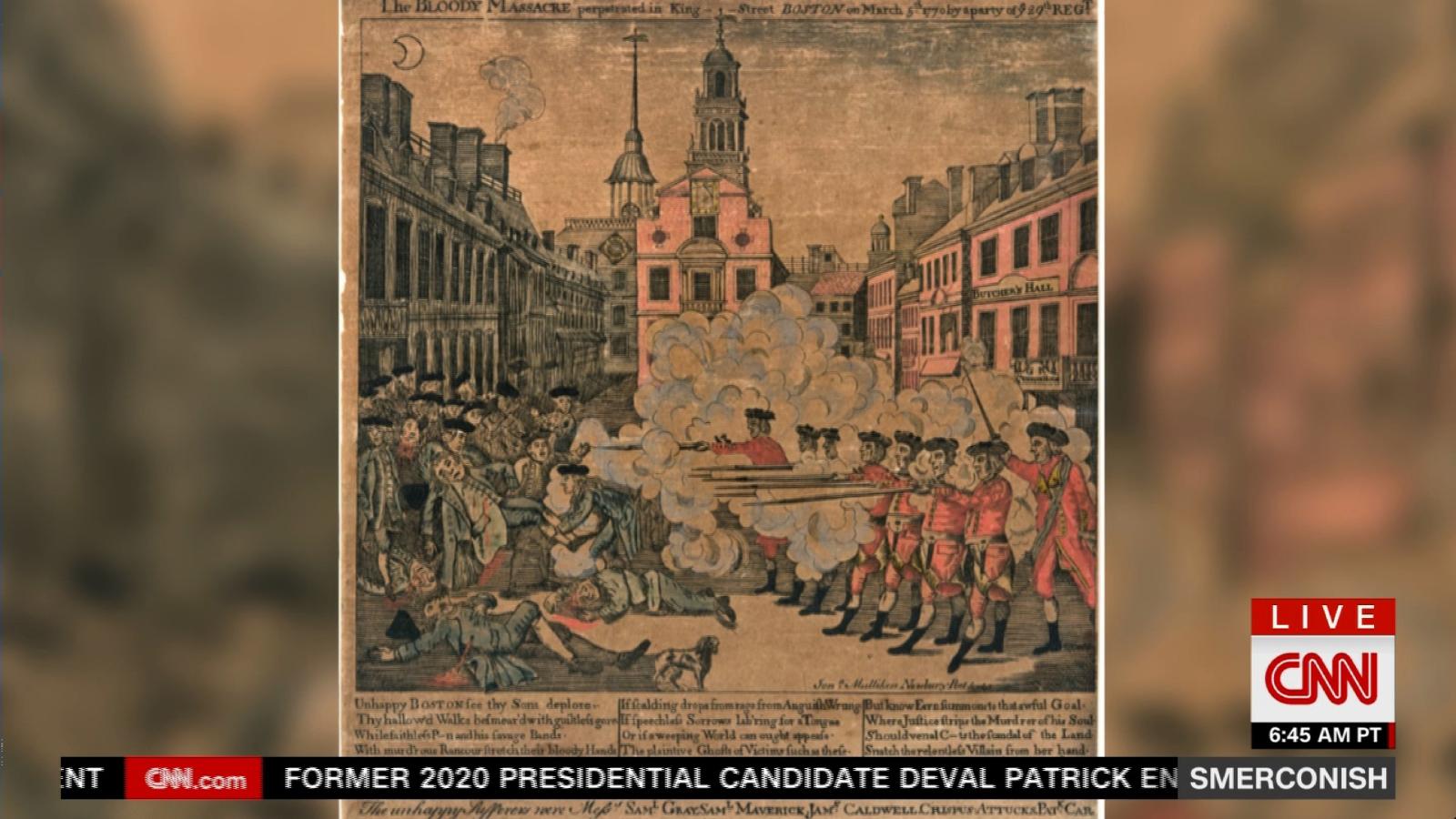

People often think the Boston Massacre was the start of the war. It wasn't. The actual fighting at Lexington and Concord didn't happen for another five years. The Massacre was a PR victory for the Patriots. Paul Revere made a famous engraving of the event—which was basically 18th-century "fake news" or at least very biased propaganda.

In Revere’s engraving, the scene looks like a daylight execution. The British are in a neat line, firing on a peaceful crowd. And—interestingly—Attucks is often depicted as a white man in early prints of that engraving, or he’s missing entirely. Revere wanted to stir up the wealthy white colonists, and he figured a Black man leading the charge wouldn't "sell" the cause as well.

🔗 Read more: Why Fox Has a Problem: The Identity Crisis at the Top of Cable News

It took decades for the visual record to catch up to the historical truth.

Why It Still Matters in 2026

We’re coming up on the 250th anniversary of the United States. When we look back at the first person killed in the Boston Massacre, it’s a reminder that America has always been a melting pot of motives. Attucks wasn't just fighting for "No Taxation Without Representation." He was fighting for a society where he could exist as a free man.

His presence on King Street proves that the Revolution belonged to everyone—the sailors, the laborers, the marginalized—not just the guys in the fancy suits in Philadelphia.

If you're looking for actionable ways to engage with this history or verify these facts, here is how you can move forward:

- Visit the Site: If you’re ever in Boston, go to the Old State House. There’s a circle of cobblestones in the ground marking the exact spot where the massacre happened. It’s right outside a subway entrance. It’s a weird, powerful feeling to stand where Attucks fell.

- Read the Trial Transcripts: You don't have to take a historian's word for it. The transcripts of Rex v. Preston are digitized. You can read exactly what witnesses said about Attucks' actions that night. It’s raw and unfiltered.

- Explore the Abolitionist Archives: Look into William Cooper Nell’s writings. He was the one who fought to get Attucks recognized in the 19th century. It shows how history is often "recovered" by those who need it most.

- Check Primary Sources: The Boston Gazette archives from 1770 give you a sense of the immediate, frantic aftermath. You can see how the story was spun in real-time.

History isn't a dead thing. It’s a constant tug-of-war between what happened and how we choose to remember it. Crispus Attucks was a man who escaped slavery, lived on the sea, and ended up at the center of a moment that changed the world. He wasn't a passive victim; he was a participant in the messy, violent birth of a nation.