Movies usually lie to us. They tell us that if you do something terrible, the universe will eventually pivot toward justice. The bad guy falls off the roof, the lie is exposed, or at the very least, guilt eats the protagonist alive until they confess. Then there is Crimes and Misdemeanors.

Released in 1989, this film basically took the "moral universe" trope and threw it out a Manhattan window. It’s a movie that asks a terrifying question: What if you commit a mortal sin and... nothing happens? No lightning bolt. No police at the door. Just a quiet life and a thriving career.

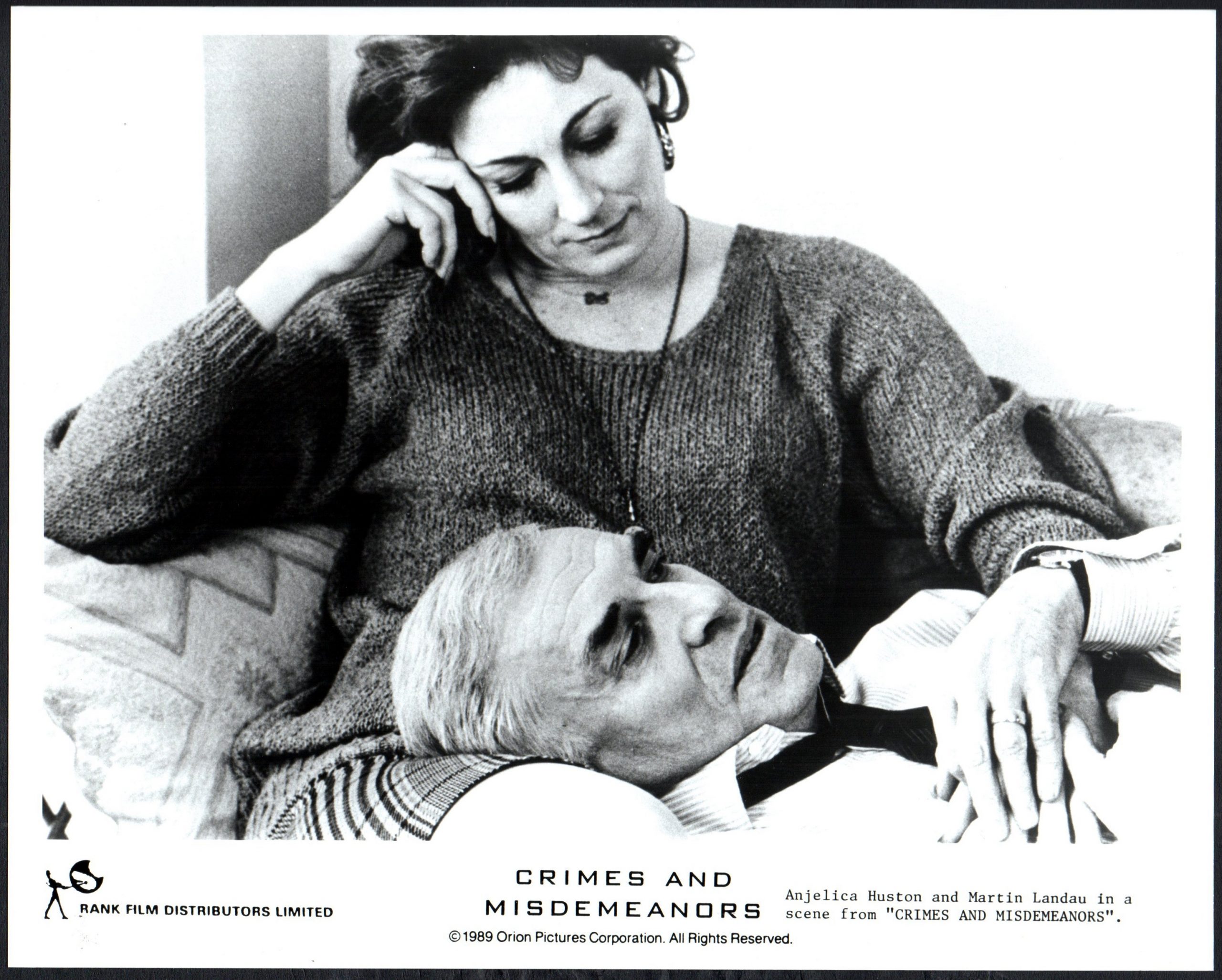

It’s honestly one of the most cynical yet deeply human pieces of cinema ever made. When we talk about Crimes and Misdemeanors, we aren't just talking about a Woody Allen flick with a stacked cast including Martin Landau and Anjelica Huston. We are talking about a philosophical interrogation of God, eyes, and the terrifying silence of the void.

The Two Worlds of Crimes and Misdemeanors

The structure of the film is kinda genius. It splits into two wildly different tones that eventually crash into each other in the final scene.

On one side, you have Judah Rosenthal (Martin Landau). He’s a "pillar of the community." A wealthy ophthalmologist. A family man. But he’s also been having an affair with a flight attendant named Dolores (Anjelica Huston), who is—to put it mildly—spiraling. She’s threatening to blow up his life. She’s writing letters to his wife. She’s calling his house.

Judah is desperate. He turns to his brother Jack, who has "unsavory" connections. Suddenly, we aren't in a comedy anymore. We are in a cold, clinical thriller. Judah hitches a ride on a dark path and decides to have Dolores murdered.

Then there’s the "Misdemeanors" side. This is the Cliff Stern (Woody Allen) plot. Cliff is a struggling documentary filmmaker who hates his life and his marriage. He gets a gig directing a puff piece about his brother-in-law Lester (Alan Alda), a pompous, ultra-successful TV producer.

Lester is the "misdemeanor" of the title—an annoyance, a fraud, a man who wins despite being insufferable. Cliff falls for a producer played by Mia Farrow, but (spoiler alert) he loses the girl and his dignity.

The contrast is jarring. You’re laughing at Alan Alda being a blowhard in one scene, and in the next, you’re watching Martin Landau stare into the abyss of his own soul after ordering a hit on a human being.

📖 Related: Wrong Address: Why This Nigerian Drama Is Still Sparking Conversations

Why Judah Rosenthal Is Cinema's Most Realistic Villain

Most movie villains are cartoons. They want to blow up the world or steal gold. Judah just wants to keep his dinner parties and his reputation. That makes him way scarier.

What Landau does with this role is incredible. He doesn't play Judah as a monster. He plays him as a man who is literally haunted by his childhood. He remembers his father saying, "The eyes of God are on us always."

But the movie’s big "twist" isn't a plot point. It’s a realization. After the murder, Judah is a wreck. He’s suicidal. He’s panicked. You think, Okay, here comes the justice. But it never comes.

Time passes. The guilt fades. Judah realizes that if you don't confess, and you aren't caught, the world just keeps spinning. He goes back to his life. He’s happy. He’s "scot-free." This is the "crime" that the movie wants you to sit with. It’s the idea that morality might just be a human invention that we use to keep ourselves from going crazy, rather than a fundamental law of the universe.

The Symbolism of Vision and Eyes

You can’t write about Crimes and Misdemeanors without mentioning the eyes. Judah is an eye doctor. His father told him God sees everything. One of the main characters, a rabbi named Ben (Sam Waterston), is literally going blind throughout the movie.

Ben represents the "leap of faith." He believes that even if the world is dark, there is a moral structure to it. The irony is thick: the man who sees the "truth" of God's love is the one whose physical eyes are failing him.

Meanwhile, Judah, the man who fixes vision, chooses to look away from what he’s done. He blinds himself to his own evil so he can survive.

Lester and the Misdemeanor of Success

Alan Alda’s Lester is maybe the most underrated part of the film. He’s not a murderer. He’s just... a jerk. He’s the guy who quotes "if it bends, it's funny; if it breaks, it's not funny" and thinks he’s a philosopher.

👉 See also: Who was the voice of Yoda? The real story behind the Jedi Master

He represents the petty injustices of life. Why does the arrogant guy get the girl? Why does the hack get the awards while the serious documentary filmmaker (Cliff) gets fired?

In a weird way, Lester’s success is just as much of an indictment of the universe as Judah’s lack of punishment. The world doesn't reward "good" or "talent." It rewards the people who know how to play the game and keep their consciences clear.

Honestly, the scene where Cliff edits the footage of Lester to look like Mussolini is cathartic, but it’s a loser’s victory. It changes nothing.

That Final Scene at the Wedding

The movie ends at a wedding. Judah and Cliff, who have never met, sit together in a quiet corner. Judah tells Cliff a "story" about a "friend" who committed a murder and got away with it.

Cliff, ever the idealist (or at least the guy who believes in movies), says that the man must eventually turn himself in. He says the story needs a "tragic" ending for it to have any meaning.

Judah looks at him and basically says, "That’s the movies. In reality, you move on."

It’s a chilling moment. It strips away the comfort of storytelling. It tells the audience that the 100 minutes they just watched wasn't a fable with a lesson—it was a mirror.

Critical Reception and Legacy

When this came out in '89, critics went nuts. It’s often cited alongside Annie Hall and Manhattan as one of Allen's "big three."

✨ Don't miss: Not the Nine O'Clock News: Why the Satirical Giant Still Matters

Vincent Canby of the New York Times praised its complexity. Roger Ebert gave it four stars, noting how it moves between comedy and tragedy without breaking a sweat. It was nominated for three Oscars, including Best Director and Best Supporting Actor for Landau.

Even people who aren't fans of Allen’s later work or personal controversies usually admit that Crimes and Misdemeanors is a technical and philosophical powerhouse. It influenced a whole generation of "moral ambiguity" cinema. You can see its DNA in everything from Match Point (which is basically a remake) to the darker turns of modern prestige TV.

What Most People Get Wrong About the Movie

People often think Crimes and Misdemeanors is a "depressing" movie. I don't think it is.

I think it’s a truthful movie. It doesn't say that you should kill people. It says that the responsibility for being a good person rests entirely on you, because the universe isn't going to do the job for you.

If there’s no God watching, then your choices matter more, not less. If you do the right thing only because you’re afraid of getting caught, are you actually a good person? Or just a coward?

That’s the nuance that gets lost in the "nihilism" label. The film isn't saying nothing matters. It’s saying that we are the ones who have to make things matter.

Actionable Insights for Cinephiles

If you’re planning to revisit this classic or watch it for the first time, keep these things in mind to get the most out of the experience:

- Watch the Lighting: Notice how the lighting in Judah’s scenes becomes increasingly cold and shadowed as his plot progresses, while Cliff’s scenes often have a warmer, almost nostalgic glow, even when he's failing.

- Compare to Dostoevsky: The film is a loose modern riff on Crime and Punishment. Reading a summary of Raskolnikov's journey before watching provides a massive amount of context for Judah's internal struggle.

- Focus on the Philosophy: Pay close attention to the documentary segments featuring Professor Louis Levy (played by real-life psychologist Martin S. Bergmann). His monologues about the universe being an "empty place" are the literal thesis of the film.

- The "Match Point" Connection: If you’ve seen Match Point, watch this immediately after. It’s fascinating to see how the same filmmaker tackled the same theme of "luck vs. morality" twenty years apart with very different results.

- Check the Soundtrack: The use of Schubert’s String Quartet No. 15 during the murder sequence is legendary for a reason. It’s a perfect example of how "high art" music can be used to underscore "low" human behavior.