The image of the "Thin Red Line" is iconic. You've seen the paintings—rows of stoic men in bright scarlet tunics standing firm against a Russian cavalry charge at Balaclava. It looks glorious. It looks professional. Honestly, though? It was a logistical nightmare that bordered on criminal negligence. When we talk about Crimean War British uniforms, we aren't just talking about fashion or military tradition. We are talking about a gear failure so massive it basically changed how the British Army functioned forever.

The war started in 1854. Britain hadn't fought a major European power since Waterloo in 1815. For forty years, the Horse Guards in London had been more concerned with how a soldier looked on parade in Hyde Park than how he survived a winter in the trenches. They wanted tight tailoring. They wanted high collars. They wanted men who looked like toy soldiers.

The Death Grip of the Leather Stock

If you want to understand the misery of a British private in 1854, start at the neck. Every soldier wore a "stock." This was a stiff, high collar made of horsehair or rigid leather. It was designed to keep a man’s head up and his eyes forward. Basically, it was a neck brace.

Imagine trying to climb the heights of the Alma or dig a trench in the freezing mud while a piece of cowhide is literally choking you. It was brutal. Soldiers hated them. During the long marches in the Bulgarian heat before they even reached the Crimea, men were dropping from heatstroke because these uniforms didn't allow for any heat dissipation. They were suffocating in the name of "smartness."

Eventually, the reality of the front line took over. Men started "losing" their stocks. They unbuttoned those restrictive collars. It was the first sign that the rigid Victorian military aesthetic was crumbling under the pressure of actual industrial warfare.

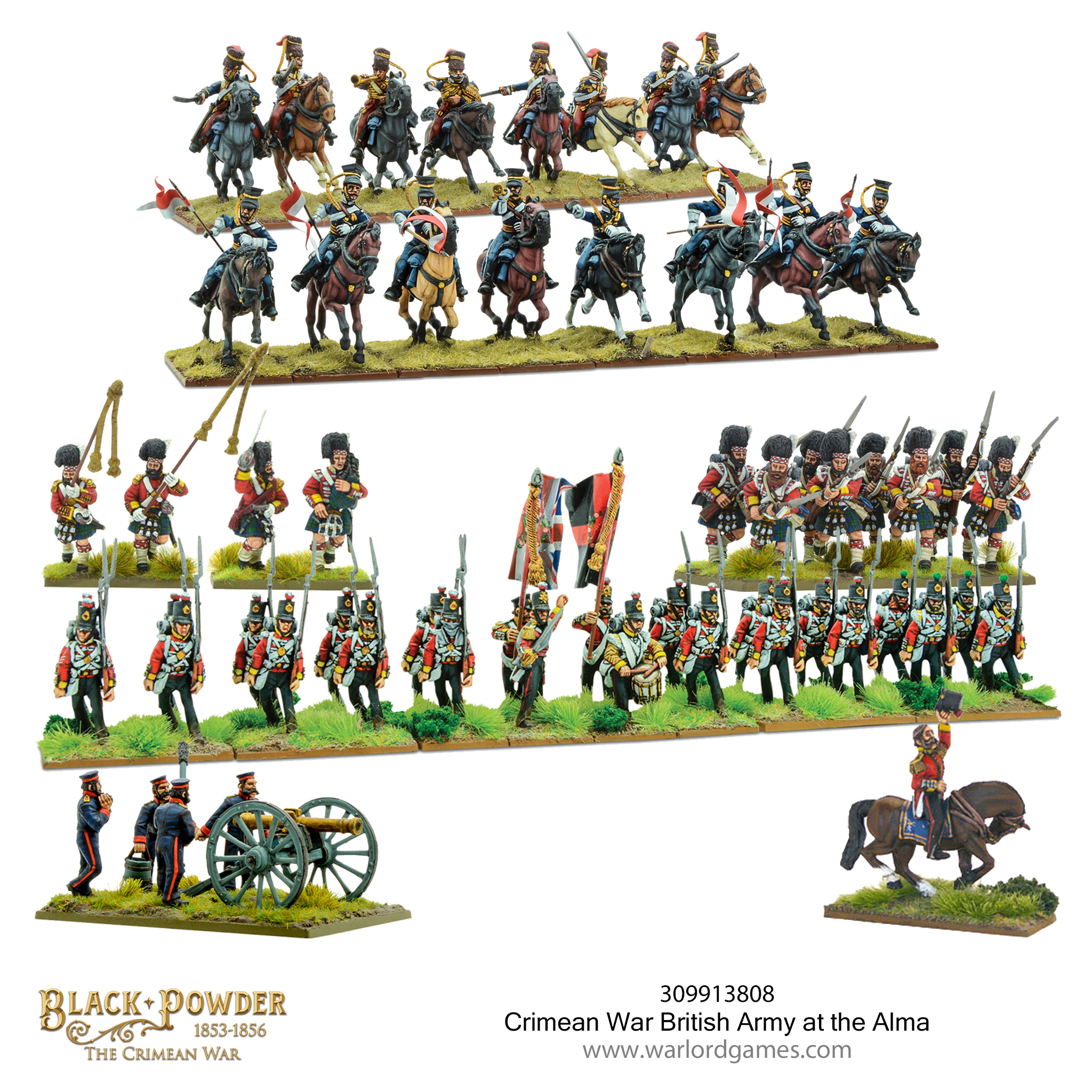

What Crimean War British Uniforms Actually Looked Like

The scarlet tunic is the big one. Everyone knows the red coat. But it’s worth noting that by 1854, the British were transitioning. The old "coatee" with its short tails was still in use by many regiments, but the longer "tunic" was just starting to appear.

Red wasn't just for show. It served a purpose. In the thick black powder smoke of a 19th-century battlefield, you couldn't see anything. You needed to know where your mates were. That bright splash of red helped officers keep their formations together when the world turned into a gray fog of sulfur and lead.

Not Everyone Wore Red

If you were a Rifleman in the 95th, you weren't in red. You were in "Rifle Green." This was early camouflage, essentially. The 95th Rifles used the Baker rifle (and later the Minié) and acted as skirmishers. They needed to hide. They wore dark green with black facings, which made them look like ghosts in the scrubland.

💡 You might also like: Converting 50 Degrees Fahrenheit to Celsius: Why This Number Matters More Than You Think

Then you had the Highlanders. Their Crimean War British uniforms were arguably the most distinctive and the most impractical for a Russian winter. They had the kilt, the feather bonnet, and the sporran. While the kilt is great for mobility, imagine being in a waist-deep trench in a blizzard with bare knees.

Historical records from the time, including letters from officers like Sir Anthony Sterling, mention how the men's legs would become raw and chapped from the freezing wind and salt spray. By the time the second winter hit, many Highlanders were desperately trying to find "trowsers" or were wrapping their legs in whatever rags they could find.

The Great Winter Disaster of 1854

This is where the story gets dark. The British government assumed the war would be over by Christmas. It wasn't.

In November 1854, a massive storm hit the Black Sea. A ship called the Prince went down. It was carrying thousands of winter kits—warm coats, boots, blankets, and woolens. Suddenly, the British Army was facing a sub-zero Russian winter in their summer-weight Crimean War British uniforms.

Men were literally freezing to death in their red coats. The wool was thin. The boots were poorly made, often with cardboard soles that disintegrated in the mud. There are accounts of soldiers’ feet swelling so much they had to cut their boots off, and then they had nothing else to wear.

"The men are in a state of utter misery... their clothing is in rags, and they have no protection against the cold." — This was the common sentiment found in the reports of William Howard Russell, the first real war correspondent for The Times.

The Rise of the Cardigan and the Balaclava

Because the official supply chain failed so spectacularly, the soldiers had to improvise. This is actually where some of our modern clothing terms come from.

📖 Related: Clothes hampers with lids: Why your laundry room setup is probably failing you

- The Cardigan: Named after James Brudenell, 7th Earl of Cardigan, who led the Charge of the Light Brigade. He wore a knitted wool waistcoat with buttons down the front to stay warm. It became a sensation back in England.

- The Balaclava: Named after the Battle of Balaclava. Since the army didn't provide enough hats, mothers and wives back home began knitting wool headgear that covered the whole face except for the eyes.

- The Raglan Sleeve: Lord Raglan, the commander of British forces, had lost an arm at Waterloo. His tailor designed a coat with a sleeve that extended all the way to the neckline, providing more room for movement and making it easier to dress. We still use this style in baseball shirts and sweatshirts today.

Footwear Failures and Scurvy

The boots were a scandal. Truly. They were "contract" boots, meaning they were made by the lowest bidder. They weren't "left" and "right"—they were "straights," designed to be worn on either foot until they broke in. But in the mud of the Crimea, they never broke in; they just fell apart.

Soldiers would find dead Russians and take their boots. Russian boots were much better suited for the terrain—taller, made of thicker leather, and more water-resistant. It’s a grim image: a British soldier in a tattered scarlet tunic, wearing a knitted "balaclava" on his head and stolen boots from a man he might have killed the day before.

This wasn't just a fashion issue. Exposure led to a massive drop in combat effectiveness. If you can't feel your toes, you can't march. If you're shivering uncontrollably, you can't aim a rifle. The Crimean War British uniforms of 1854 nearly lost Britain the war before the fighting really got started.

Evolution: The 1855 Pattern

By 1855, the outcry in London was so loud that the government was forced to act. The "1855 Pattern" tunic was introduced. It was a more practical, double-breasted coat (later becoming single-breasted) that was looser and warmer.

The leather stock was finally ditched for a simpler cloth version. The "Albert Shako"—that tall, heavy hat—was replaced by the "French-style" kepi or the "low-crowned" shako which was much lighter.

They also started issuing the "Greatcoat" in larger numbers. This was a heavy, grey-blue wool overcoat that actually stood a chance against the wind. But for thousands of men, these changes came a year too late.

Rank and File vs. Officers

It's important to remember that officers bought their own uniforms. If you were a wealthy Lieutenant, you could afford high-quality wool, custom-tailored coats, and fur linings. The common soldier—the man earning a shilling a day—was stuck with whatever the government issued.

👉 See also: Christmas Treat Bag Ideas That Actually Look Good (And Won't Break Your Budget)

This created a weird visual on the battlefield. You’d have officers looking quite dapper in their tailored tunics, while their men looked like bedraggled scarecrows. As the siege of Sevastopol dragged on, even the officers gave up on regulations. They wore whatever kept them warm: goatskin coats, fur hats bought from locals, and non-regulation scarves.

The Legacy of the Crimean Kit

So, why does this matter now? Because the Crimean War was the turning point for military logistics. It was the moment the British military realized that "looking the part" wasn't enough.

The failures of the Crimean War British uniforms led to the reform of the Army Clothing Department. It led to standardized sizing. It led to the realization that the soldier's health was directly tied to the quality of his gear.

The war also gave us the Victoria Cross, the nursing legacy of Florence Nightingale, and a complete overhaul of how the British public viewed their soldiers. They weren't just the "scum of the earth" (as Wellington once called them); they were heroes who were being let down by their own equipment.

Summary of Key Features

- Scarlet Tunics: Moving from the old coatee to the longer tunic style.

- The Stock: A rigid leather neck collar that was widely despised.

- Headgear: The Albert Shako, which was eventually replaced by more practical caps.

- Equipment: The transition from the smoothbore Musket to the Minié Rifle, which required different ammunition pouches and belts.

- Knitted Innovations: The birth of the cardigan and the balaclava out of sheer necessity.

How to Spot Authentic Crimean Gear Today

If you're a collector or a history buff, you have to be careful. A lot of "Crimean" uniforms you see in museums are actually later Victorian patterns.

Authentic 1854-pattern tunics are incredibly rare. Most of them were worn to rags in the trenches and thrown away. Look for the specific button arrangements and the height of the collar. Real Crimean-era tunics usually have a very high, stiff collar compared to the 1870s or 1880s versions.

Also, look at the lace. In 1854, different regiments had different "bastion-shaped" or pointed lace on their cuffs. After the war, this became much more standardized.

Actionable Insights for Researchers and Enthusiasts

- Check the Buttons: Regimental buttons are often the only way to identify a surviving garment. The numbering system on the buttons will tell you exactly which unit the soldier belonged to.

- Consult the National Army Museum: They have some of the few remaining authentic examples of the 1855 pattern tunics. Their digital archives are a goldmine for seeing the actual weave of the wool.

- Read the Letters: To understand how the uniforms felt, don't just look at photos of reenactors. Read "Letters from the Crimea" by various soldiers. They talk about the weight, the smell, and the sheer discomfort of the gear.

- Watch for "Revenge" Patterns: Many later Victorian uniforms were designed specifically to fix the problems found in the Crimea. If a uniform looks "too comfortable," it’s probably post-1860.

The Crimean War British uniforms represent a bridge between the Napoleonic era and modern warfare. They were the last gasp of 18th-century elegance meeting 19th-century industrial reality. The results were tragic, messy, and ultimately transformative. Next time you put on a cardigan or pull on a balaclava for a ski trip, remember that those pieces of clothing were born in the freezing mud of a Russian peninsula by men just trying to survive the night.