You’ve heard the opening riff of "Fortunate Son" a thousand times. Maybe it was in a Vietnam War movie, or maybe it was just blasting from a truck in a grocery store parking lot. It’s got that raw, gritty snarl that feels like it belongs to the mud and the mosquitoes of the South. But here’s the kicker: Creedence Clearwater Revival (CCR) wasn’t from the bayou. They were basically just some kids from El Cerrito, California.

John Fogerty, the guy behind nearly all the hits, had this weird, brilliant obsession with the deep South. He wrote about riverboats and hoodoos while living in the San Francisco Bay Area. It’s kinda wild when you think about it. He created a whole world—"swamp rock"—without actually being from the swamp. And people bought it. Man, did they buy it.

The Weird Chart Curse of Creedence Clearwater Revival Songs

If you look at the Billboard charts from 1969 to 1971, CCR was everywhere. They were arguably the biggest band in the world for a minute there, even outselling the Beatles in 1969. But they have this really bizarre, frustrating record.

They’re the "eternal bridesmaids" of rock and roll.

🔗 Read more: Cry Havoc: Why Jack Carr Just Changed the Reece-verse Forever

Basically, CCR holds the record for the most singles to hit number two on the Billboard Hot 100 without ever actually reaching number one. They had five songs peak at the second spot. It’s almost impressive how they kept getting blocked. "Proud Mary" was stuck behind Tommy Roe’s "Dizzy." "Bad Moon Rising" couldn't get past "Love Theme from Romeo and Juliet." Honestly, it feels like the universe was trolling them.

The Hits That Almost Made It

- Proud Mary: Their first big swing at number two. It’s a song about a riverboat, inspired by a notebook Fogerty bought at a drugstore.

- Bad Moon Rising: Total impending doom vibes, but everyone just sings "there's a bathroom on the right."

- Green River: A nostalgia trip for a childhood vacation spot at Putah Creek in California.

- Travelin’ Band: A high-energy tribute to 50s rock and roll that got them sued because it sounded a bit too much like Little Richard.

- Lookin' Out My Back Door: A trippy, upbeat tune that sounds like a drug trip but was actually written for Fogerty's three-year-old son.

Why the Music Sticks 50 Years Later

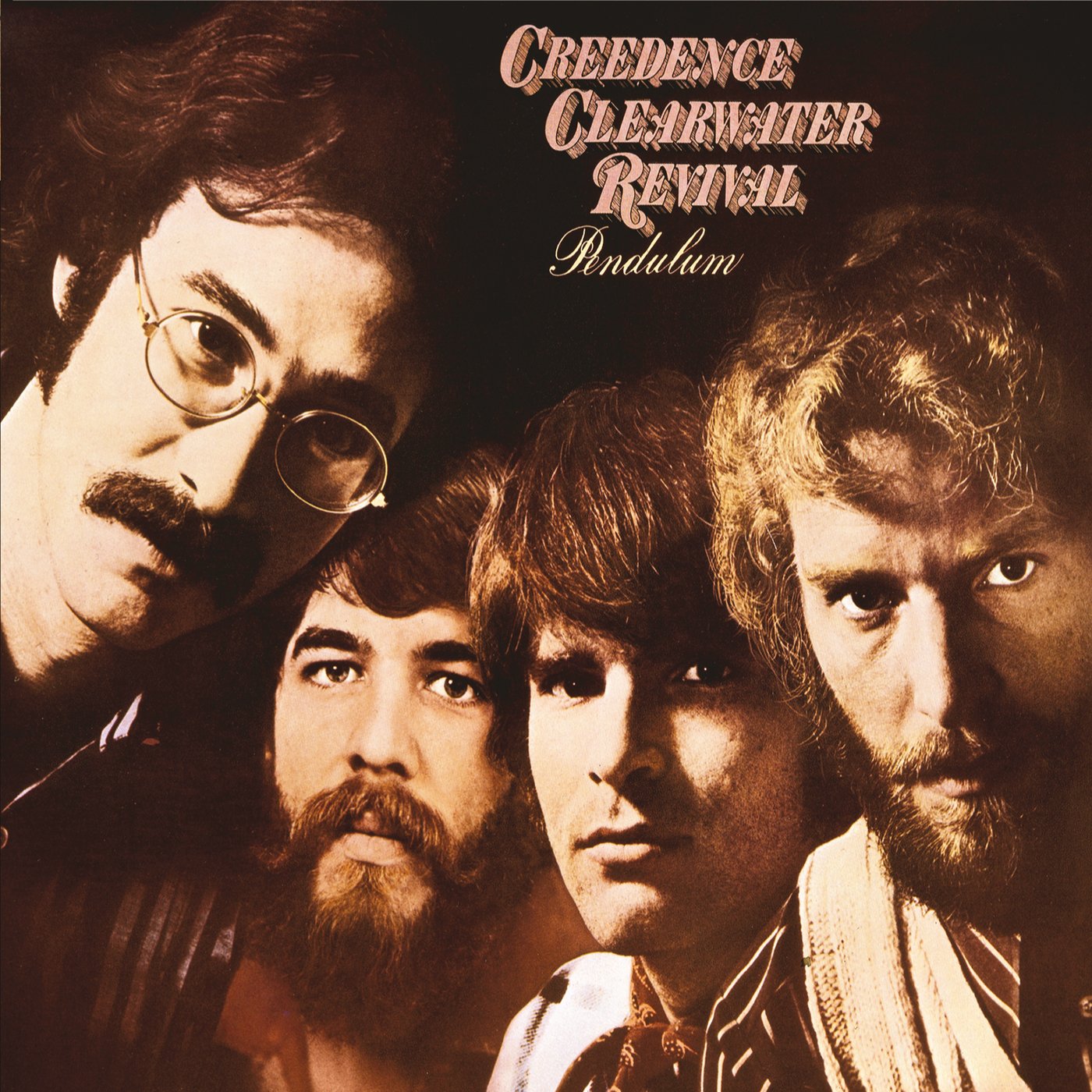

There is a specific "tightness" to Creedence Clearwater Revival songs that most bands can't replicate. John Fogerty was a perfectionist. He famously drilled the band—his brother Tom, bassist Stu Cook, and drummer Doug Clifford—in a warehouse they called "The Factory."

They didn't jam. They didn't do 20-minute psychedelic solos like the Grateful Dead. They got in, played the hook, delivered the message, and got out. Most of their hits are under three minutes. That’s why they work so well on the radio. They are engineered to be catchy, but they have enough grit to keep them from sounding like bubblegum pop.

💡 You might also like: Colin Macrae Below Deck: Why the Fan-Favorite Engineer Finally Walked Away

The Political Undercurrent

While songs like "Down on the Corner" are just fun stories about street musicians, a lot of CCR’s catalog is surprisingly dark. Take "Fortunate Son." It’s not just a "war song." It’s a class-war song. Fogerty wrote it after seeing David Eisenhower (the former President's grandson) marry Julie Nixon. He was looking at how the kids of the elite got to stay home while everyone else got shipped off.

Then you’ve got "Run Through the Jungle." People assume it's about Vietnam. It’s actually about gun control. Fogerty has said he was worried about the proliferation of guns in America. The fact that these songs still feel relevant in 2026 says a lot about his songwriting. He wasn't just writing for the hippie era; he was writing about human nature.

The Covers and the Legacy

You can’t talk about CCR without mentioning their covers. "Susie Q" was their first hit, and it’s the only Top 40 song they had that John Fogerty didn't write. It was originally a Dale Hawkins track. They also did an 11-minute version of "I Heard It Through the Grapevine" that basically reinvented the Marvin Gaye classic into a swampy marathon.

📖 Related: Cómo salvar a tu favorito: La verdad sobre la votación de La Casa de los Famosos Colombia

Even when they were covering people, they made it sound like it was born in a garage in 1969.

The band eventually imploded, of course. Internal fighting over who got to write songs and how the money was handled tore them apart by 1972. Tom Fogerty left first, and the final album, Mardi Gras, was a bit of a disaster because John insisted everyone else write their own tracks to "be fair." It didn't work. Critics hated it.

Actionable Ways to Experience CCR Today

If you want to actually understand why this band matters beyond the "Forest Gump" soundtrack, stop listening to the radio edits and try these steps:

- Listen to the album Cosmo's Factory in one sitting. It is arguably one of the greatest "hit-to-filler" ratios in history. Almost every song on it could have been a single.

- Check out the live footage from the 1970 Royal Albert Hall show. You can see how much energy they actually had. They weren't just a studio band; they were a powerhouse live act that didn't need flashy lights to command a room.

- Dig into the B-sides. Songs like "Lodi" or "Effigy" show a much more vulnerable, weary side of the band that doesn't always make the "Greatest Hits" collections.

The story of CCR is kinda tragic in the end—lawsuits that lasted decades and a brotherhood that never really healed before Tom passed away. But the music? The music is bulletproof. It doesn't matter if you're in a bar in 2026 or a bunker in 1970; when that riff starts, you’re going to turn it up.