You’re staring at a grid. There’s a line—or maybe a curve—cutting through it like a scar across a map. Your teacher or a standardized test or maybe a physics simulation is asking you to turn that visual mess into a neat mathematical sentence. Basically, you need to create equation from graph without losing your mind in the process. It looks intimidating. Honestly, though? It’s just reverse engineering. If you can read a map, you can do this.

Most people fail because they try to memorize five different "steps" that all sound the same. They get bogged down in the minutiae of whether a sign is positive or negative. They forget the big picture. Mathematics is just a language describing a shape. When you look at a graph, the "equation" is simply the set of rules that tells a point where to sit on the paper.

The Linear Shortcut: Slopes and Intercepts

Linear graphs are the bread and butter of algebra. They are straight. They are predictable. If you see a straight line, you are looking for the classic $y = mx + b$. This is the slope-intercept form, and it's your best friend.

First, find the y-intercept. This is the point where the line smacks right into the vertical y-axis. It’s the easiest thing to spot. If the line crosses at $(0, 3)$, then your $b$ is $3$. Simple. No math required yet. Just eyes.

Now, the slope. This is $m$. You’ve probably heard "rise over run" until your ears bled. But think of it as a rate of change. If you move one unit to the right, how many units do you go up or down? If you move over $1$ and go up $2$, your slope is $2$. If you go down $3$, your slope is $-3$.

Let’s say you have a line that crosses the y-axis at $-1$ and for every $2$ squares you move right, you go up $1$ square. Your equation is $y = 0.5x - 1$.

Sometimes the points aren’t "clean." You might see a point at $(1, 2)$ and another at $(4, 11)$. You can’t just eyeball the slope. You need the formula: $m = (y_2 - y_1) / (x_2 - x_1)$.

In this case, $(11 - 2) / (4 - 1)$, which is $9 / 3$. So, $m = 3$.

🔗 Read more: Why the Pen and Paper Emoji is Actually the Most Important Tool in Your Digital Toolbox

Plug it back in: $y = 3x + b$. Use one of your points to find $b$.

$2 = 3(1) + b$.

$2 = 3 + b$.

$b = -1$.

The final result? $y = 3x - 1$.

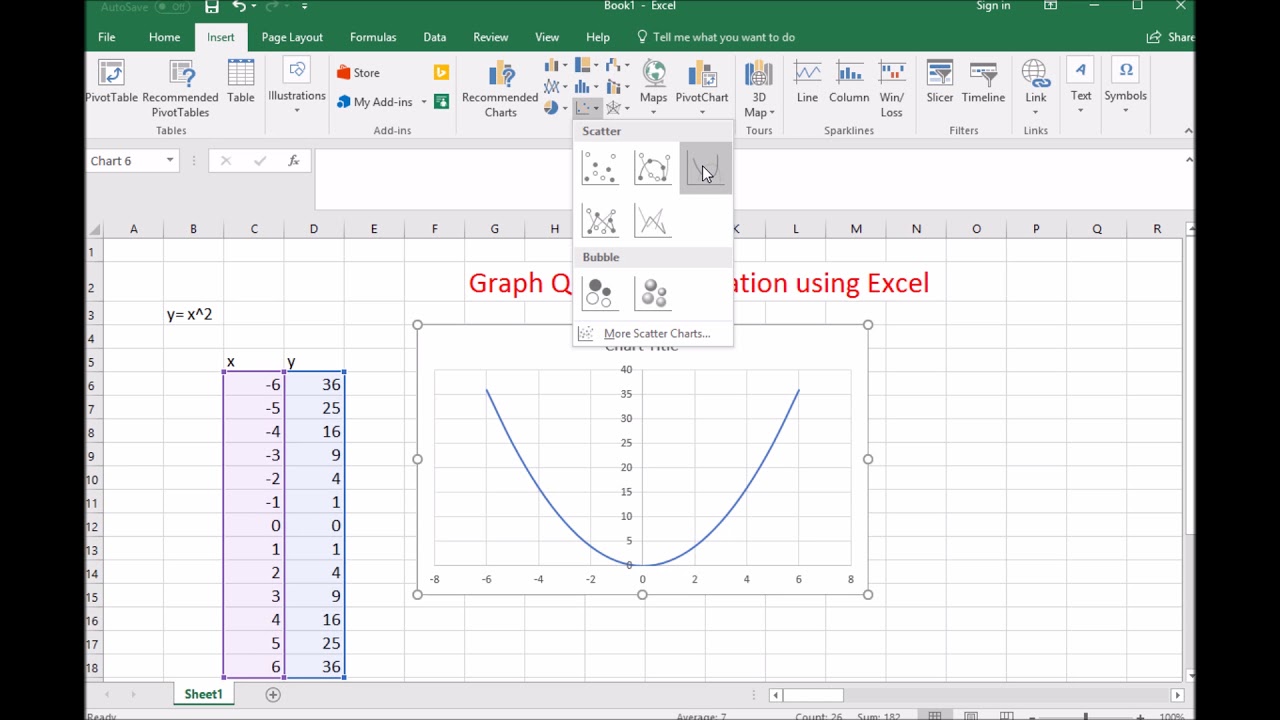

When the Line Curves: Dealing with Parabolas

Straight lines are easy, but the world is curvy. Quadratic equations create that distinct "U" shape called a parabola. To create equation from graph for a curve, you need to look for the "vertex"—the very bottom or very top of the hill.

The vertex form is usually the path of least resistance: $y = a(x - h)^2 + k$.

Here, $(h, k)$ is the vertex. If the bottom of your "U" is at $(2, -4)$, then $h = 2$ and $k = -4$.

Your equation starts as $y = a(x - 2)^2 - 4$.

How do you find $a$? This is the "stretch" factor. If $a$ is positive, the "U" opens up. If it’s negative, it opens down. To find the exact number, pick any other point on the curve. Let's say the graph passes through $(0, 0)$.

$0 = a(0 - 2)^2 - 4$

$0 = 4a - 4$

$4 = 4a$

$a = 1$

Final equation: $y = (x - 2)^2 - 4$.

💡 You might also like: robinhood swe intern interview process: What Most People Get Wrong

If the graph looks like a "V" instead of a "U," you’re dealing with absolute value. The logic is identical to the parabola, but the squared part is replaced with bars: $y = a|x - h| + k$. Don't let the shape fool you; the mechanics of finding the equation are the same.

The Mystery of the Periodic Wave

Trigonometry scares people. It shouldn't. If you see a wave—something that goes up and down repeatedly like a heart monitor—you’re looking at a sine or cosine wave.

You need four things:

- Midline: The horizontal center of the wave.

- Amplitude: How far it rises above or sinks below that center.

- Period: How long it takes to complete one full cycle.

- Phase Shift: Where it starts on the x-axis.

If the wave starts at its highest point on the y-axis, use cosine. If it starts in the middle, use sine.

Suppose a wave oscillates between $y = 10$ and $y = 2$. The middle is $6$. That’s your vertical shift. The distance from $6$ to $10$ is $4$. That’s your amplitude. If it takes $2\pi$ to repeat, your frequency is $1$.

Equation: $y = 4 \cos(x) + 6$.

Practical Reality and Limitations

In the real world, data is rarely perfect. If you are trying to create equation from graph based on a scatter plot of real-world data—like stock prices or carbon emissions—you won't find a single line that hits every point.

📖 Related: Why Everyone Is Looking for an AI Photo Editor Freedaily Download Right Now

This is where "regression" comes in.

Statisticians use the "Least Squares" method. It’s a way of drawing a line that minimizes the square of the vertical distance between the line and every single point. You aren't going to do this by hand. You'll use a tool like Desmos, Excel, or a TI-84.

However, understanding the type of graph matters most.

Does the data grow faster and faster? It's exponential ($y = ab^x$).

Does it level off at a certain point? It might be logarithmic or a logistic curve.

Experts like Dr. Eugenia Cheng often emphasize that math is about patterns, not just numbers. If you see a pattern where the "rate of growth" is itself growing, you aren't looking at a line. You’re looking at acceleration.

Why Does This Actually Matter?

It’s not just for passing a test.

Engineers use these graphs to determine if a bridge will collapse under a certain load. They plot the stress vs. the strain and create an equation to predict the breaking point.

Data scientists at companies like Netflix use graphs of your viewing habits to create "equations" (algorithms) that predict what you want to watch next. They are essentially doing exactly what you’re doing on your graph paper, just with millions of data points and higher-dimensional grids.

Common Pitfalls to Avoid

Watch your signs. This is where everyone messes up. In the vertex form $y = a(x - h)^2 + k$, notice the minus sign before the $h$. If your vertex is at $x = 5$, the equation looks like $(x - 5)$. If the vertex is at $x = -5$, the equation looks like $(x + 5)$ because you’re subtracting a negative. This trips up even the smartest students.

Also, check your scale. Sometimes a graph's x-axis counts by $1$s, but the y-axis counts by $10$s. If you don't look at the labels, you’ll calculate a slope of $1$ when it’s actually $10$. It sounds stupid, but it's the number one cause of "wrong" equations in professional settings.

Actionable Next Steps

- Identify the Parent Function: Is it a line, a U-shape, a V-shape, or a wave? Don't start calculating until you know what family it belongs to.

- Find the "Anchors": Look for intercepts or the vertex. These are your $b$, $h$, and $k$ values. They give you the "location" of the graph.

- Calculate the Rate: Find the slope ($m$) or the stretch factor ($a$). Use two points to be certain.

- Verify with a Test Point: This is the most important step. Once you have your equation, pick a point from the graph that you didn't use to build the equation. Plug the $x$ into your new equation. If the $y$ matches the graph, you’ve nailed it.

- Use Technology to Confirm: Use a tool like Desmos. Type in your equation and see if it overlays perfectly on your original graph. If it doesn't, check your signs first.