Ever wonder how a thick, sludge-like goo pulled from deep underground turns into the transparent juice that powers a Lamborghini or the sleek casing of your smartphone? It feels like alchemy. Honestly, it’s just cracking in chemistry. Without this specific process, our modern world literally stops moving. We’d have mountains of heavy oil we couldn't use and zero gasoline for the morning commute.

Cracking is the industrial equivalent of taking a long, tangled string of pearls and snipping it into smaller, more manageable pieces. Crude oil is a messy soup of hydrocarbons. Some are short and light; others are massive, heavy molecules with dozens of carbon atoms chained together. The problem? We don't have much use for the heavy stuff. We want the light stuff. So, we break—or "crack"—those big molecules.

🔗 Read more: Mach to Kilometers per Hour: Why That Simple Conversion Is Kinda Lying To You

What’s Actually Happening Inside the Reactor?

At its core, cracking in chemistry is the process of breaking down long-chain hydrocarbons into shorter-chain alkanes and alkenes. It’s a thermal decomposition reaction. You take a heavy fraction, like gas oil, and you blast it with heat. Sometimes you use a catalyst to speed things up without needing temperatures that would melt the sun.

Think about the bond between two carbon atoms. It’s strong. To snap that bond, you need a significant input of energy. When that bond finally breaks, you get two smaller fragments. Usually, one is a shorter alkane (useful for fuels) and the other is an alkene (the holy grail for the plastics industry). If you’ve ever used a plastic bag or a PVC pipe, you’re looking at the direct descendants of a cracking reaction.

Thermal vs. Catalytic: Picking Your Poison

Not all cracking is the same. Refineries switch their methods based on what they want to sell that week.

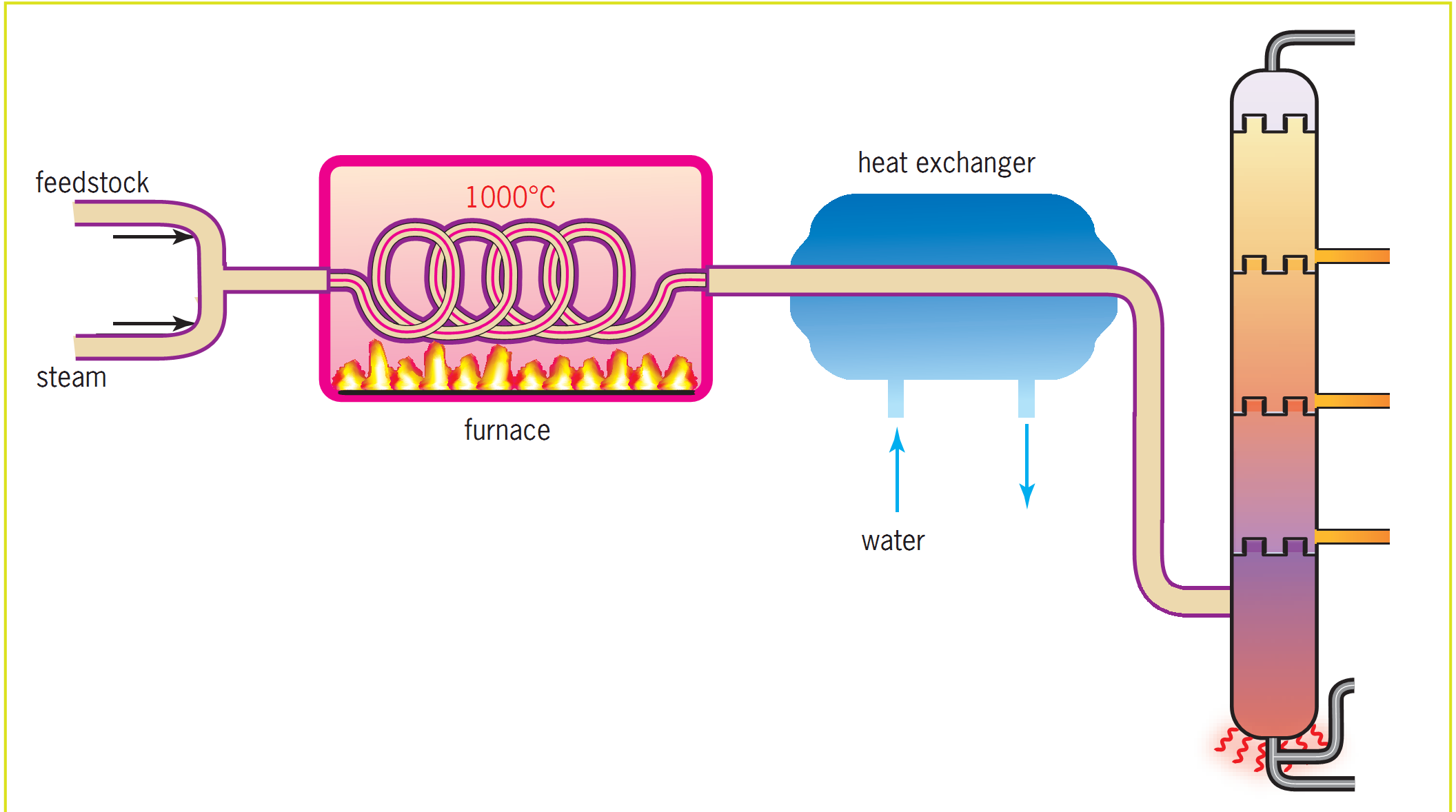

Thermal cracking is the brute force method. It’s old school. You heat the heavy hydrocarbons to temperatures between 450°C and 750°C. You also crank up the pressure. This high-energy environment shatters the molecules randomly. It's effective but hard to control. One of the most common versions today is steam cracking. This is how we get ethene. We mix the hydrocarbon feed with steam, heat it briefly in a furnace, and—boom—you’ve got the building blocks for polyethylene.

Then there is Catalytic Cracking, specifically Fluid Catalytic Cracking (FCC). This is the crown jewel of modern refining. Instead of just using raw heat, we introduce a catalyst, usually a zeolite. Zeolites are fascinating; they are aluminosilicates with a honeycomb-like structure on a microscopic level.

The catalyst does something brilliant. It lowers the activation energy required for the reaction. This means we can crack molecules at lower temperatures (around 500°C) and lower pressures. More importantly, it gives us more control. FCC is the reason we have high-octane gasoline. It tends to produce more branched-chain alkanes and aromatic compounds, which burn much smoother in your car engine than straight-chain molecules. If your engine doesn't "knock," thank a zeolite.

Why Do We Even Bother?

It’s all about the "Demand vs. Supply" gap.

💡 You might also like: Hisense TV Screen Mirroring: What Most People Get Wrong

If you just distill crude oil—basically boiling it and catching the vapors—you get a specific set of fractions. The issue is that the natural "yield" of gasoline from crude oil is pretty low. Maybe 20%. But the world's hunger for gasoline is massive. Conversely, crude oil gives us way more heavy fuel oil than we actually need for ships or factories.

Cracking fixes the math.

- Balance: It converts the surplus of heavy, low-value fractions into high-demand, high-value light fractions.

- Alkenes: Distillation doesn't really give us alkenes like ethene or propene. Cracking does. These are the "feedstock" for the entire petrochemical industry.

- Octane Rating: As mentioned, catalytic cracking reshapes molecules to make them better fuels.

The Chemistry of the Break

Let's look at a simple example. Imagine a molecule of decane ($C_{10}H_{22}$). It’s a bit too heavy for high-performance fuel. When we subject it to cracking in chemistry, it might split like this:

$$C_{10}H_{22} \rightarrow C_{8}H_{18} + C_{2}H_{4}$$

In this scenario, we’ve produced octane (a prime component of petrol) and ethene (used for plastic). It’s a win-win. But it doesn't always break that cleanly. You might get a mixture of propanes, butanes, and pentanes. This is why refineries have massive fractionation columns following the cracker—to sort out the mess we just created.

🔗 Read more: How Do You Delete on a Chromebook: What Most People Get Wrong

The Environmental Elephant in the Room

We can’t talk about cracking without acknowledging the footprint. It is an energy-intensive process. Refineries are among the largest industrial emitters of $CO_{2}$ because of the heat required to snap those carbon bonds.

However, the industry is shifting. There’s a lot of research into "Electric Cracking." Instead of burning fossil fuels to heat the furnaces, companies like BASF and Shell are testing large-scale e-furnaces powered by renewable energy. If we can crack molecules using wind or solar power, the carbon footprint of every plastic bottle and gallon of gas drops significantly.

Misconceptions People Have About Cracking

A lot of folks get cracking confused with distillation. They aren't the same. Distillation is a physical change—it’s just sorting molecules by their boiling points. No bonds are broken. Cracking is a chemical change. You are literally destroying one substance to create others.

Another weird myth is that cracking is "unnatural." In reality, the earth does its own version of cracking over millions of years through geothermal heat, which is how some lighter oils form naturally underground. We’re just doing it in seconds inside a steel vessel.

Real-World Impact: From Sneakers to Medicine

Look around your room. If it's not made of wood or metal, cracking in chemistry probably had a hand in it.

- Polyester clothing: Derived from paraxylene, a product of catalytic reforming and cracking.

- Aspirin: The precursors for many synthetic drugs come from the aromatic rings produced during high-temperature cracking.

- Synthetic Rubber: Your car tires rely on butadiene, a byproduct of steam cracking.

What Should You Do With This Information?

If you’re a student, focus on the mechanisms. Understand the carbocation intermediates in catalytic cracking—that’s usually what trips people up on exams. The catalyst works by accepting a hydrogen atom, creating a positively charged carbon atom that is inherently unstable and prone to snapping.

For everyone else, it’s a lesson in resourcefulness. Cracking is the ultimate recycling project. It takes the "waste" of the oil world and turns it into the essentials of modern life.

Next Steps for Deep Learning:

- Research Zeolites: Look into how their pore size dictates exactly which molecules can be cracked. It's like a molecular "shape sorter" toy.

- Check the Label: Look at the plastic resin codes on your household items. A "1" (PET) or "2" (HDPE) is a direct result of the ethene produced in steam crackers.

- Follow Energy News: Keep an eye on "Green Hydrogen" integration in refineries. It’s the next big leap in making the cracking process less taxing on the planet.

Understand the bond, understand the break. That’s the secret to the modern industrial age.