Australia is basically a giant cattle station with some cities clinging to the edges. If you've ever driven more than an hour inland from the coast, you've seen them—those patches of white, black, or brown dots stretching out toward the horizon. But here’s the thing. Most people just see "cows." They don't see the centuries of brutal selective breeding, the complex genetics required to survive a 45-degree day in the Kimberley, or the massive difference between a beast destined for a high-end Tokyo steakhouse versus one that's going to end up as a burger in a local pub. Understanding the various cow types in Australia isn't just for farmers. It’s for anyone who wants to know why their steak costs fifty bucks or why certain regions in this country look the way they do.

It’s a massive industry. We are talking about roughly 24 to 26 million head of cattle depending on whether we’re in a drought cycle or a "good" year. Australia is one of the world's largest exporters of beef, and that doesn't happen by accident. It happens because we’ve spent a long time figuring out which animals don't keel over when the grass turns to dust.

The North-South Divide: Why Climate Dictates the Breed

In Australia, the "Great Dividing Range" isn't just a mountain chain; it’s a genetic border.

If you go south—Victoria, Tasmania, southern NSW—you’re in British and European territory. Think lush green hills, reliable rain (mostly), and freezing winters. Here, the Angus is king. You know the one. Solid black, no horns, looks like a rectangular block of granite. Angus cattle are the darlings of the culinary world because they marble like crazy. Intramuscular fat is the secret sauce of a good steak, and Angus has it in spades. They thrive in the cold but, honestly, they hate the heat. Put a black Angus in the middle of a Queensland summer and it’ll spend the whole day standing in a dam trying not to melt.

Then there’s the North.

Up in the Northern Territory and the top of Queensland, the environment is hostile. We’re talking ticks, buffalo flies, and humidity that feels like breathing through a wet towel. A British cow won't last a week up there. Enter the Brahman. Originally from India, these guys are the superheroes of the Australian outback. You’ve seen them—big humps on their shoulders, floppy ears, and loose, saggy skin. That skin isn't just for show; it increases the surface area for cooling, and they have more sweat glands than southern breeds. Plus, their skin is thick enough that ticks can't get a good grip.

But Brahmans have a reputation. They’re smart. Maybe too smart. A Brahman won't just stand there if it doesn't like what you're doing; it’ll jump a six-foot gate or take a run at you if it's feeling cranky.

📖 Related: Blue Bathroom Wall Tiles: What Most People Get Wrong About Color and Mood

The Rise of the "Composite" and the Wagyu Craze

Farmers got tired of choosing between "hardy but lean" and "tender but fragile." So, they started playing god. This led to the rise of Composites and Crossbreeds.

The Brangus is exactly what it sounds like: a mix of Brahman and Angus. You get the meat quality of the Angus with the heat tolerance of the Brahman. It’s the "Goldilocks" of the Australian beef world. You'll see them all over Central Queensland. They have a slight hump, but they're mostly black and carry way more muscle than a pure Brahman.

Then there is the Santa Gertrudis. Developed on the King Ranch in Texas but perfected in Australia, these deep-red beasts are a mix of Shorthorn and Brahman. They’re massive. If you see a sea of dark red cattle in the scrub, that’s likely what they are.

Let's talk about the Wagyu

We can't discuss cow types in Australia without mentioning the Japanese influence. Australia actually has the largest herd of Wagyu outside of Japan. It’s a niche that exploded. Purebred Wagyu are small, slow-growing, and honestly a bit funny-looking. But their meat is the "caviar of beef." Most Australian Wagyu is actually a "F1" cross—usually a Wagyu bull over an Angus cow. This gives the farmer a bigger animal that still produces that incredible, buttery marbling.

David Blackmore is a name you’ll hear in this space. He’s essentially the godfather of Australian Wagyu, having pioneered the genetics here in the 80s and 90s. His beef sells for hundreds of dollars a kilo in high-end restaurants. It's a completely different world from the commercial cattle auctions in Roma or Tamworth.

The Dairy Side of the Fence

While beef gets all the glory and the "cowboy" imagery, the dairy industry is the backbone of many regional towns. Here, the diversity is lower because the job is more specific: turn grass into white gold as efficiently as possible.

👉 See also: BJ's Restaurant & Brewhouse Superstition Springs Menu: What to Order Right Now

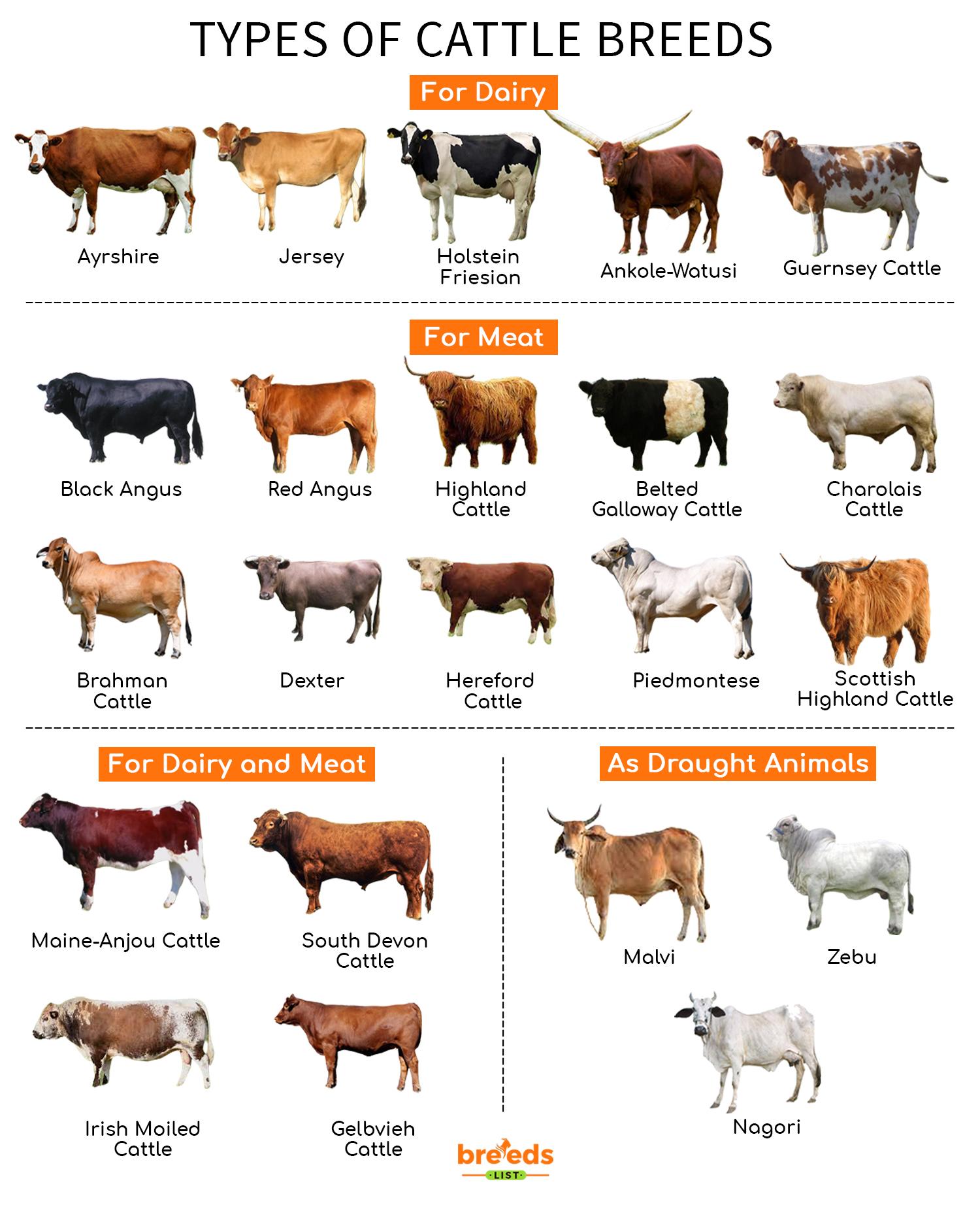

The Holstein-Friesian is the classic "Chick-fil-A" cow—black and white patches. They are the heavy hitters. A good Holstein can produce 30 or 40 litres of milk a day. They are massive animals, but they require a lot of groceries. If you don't feed them high-quality grain and pasture, their production drops off a cliff.

On the other hand, you have the Jersey.

Smaller, brown, with big "Disney" eyes. If a Holstein is a freight train, a Jersey is a refined sports car. Their milk is much higher in butterfat and protein, which is why it tastes "creammier." Most of the fancy cheeses and premium butters you buy come from Jersey herds. They are also much tougher than Holsteins. They handle the heat better and are generally easier to manage, though they can be a bit more "opinionated" during milking.

Why Does This Matter to You?

Honestly, it matters because of the label on your meat.

If you see "Pasture Raised" or "Grass Fed," you're likely eating a breed that can convert rough forage into protein effectively—think Herefords (the red ones with white faces) or Shorthorns. These breeds were the original pioneers. They came over on the early ships and survived on whatever they could find. They produce beef with a distinct, slightly earthy flavor.

If you're buying "Grain Fed," you're often eating Angus or a composite that has been finished in a feedlot for 100 days. This gives you that consistent, predictable tenderness that many consumers crave.

✨ Don't miss: Bird Feeders on a Pole: What Most People Get Wrong About Backyard Setups

The Forgotten Breeds

We also have "heritage" or "rare" breeds that are making a comeback. The Belted Galloway (the "Oreo cow") is incredibly hardy and produces great beef, but it grows slowly, so big commercial farms hate it. Then there’s the Murray Grey. This is a true-blue Aussie original. It started as a genetic accident in the upper Murray Valley in 1905—a light-coloured calf born to an Angus. People realized these "grey" cows were exceptionally calm and grew quickly. They’re beautiful animals, silvery-grey and very docile.

What to Look for Next Time You’re Out

Next time you’re driving through the NSW Southern Highlands or the Queensland Brigalow country, try to spot the differences.

- White face, red body? That’s a Hereford. Reliable, sturdy, the "old faithful" of the bush.

- Solid black and blocky? Angus. The premium market leader.

- Big hump and floppy ears? Brahman. The king of the north.

- Silver or dusty grey? Murray Grey. The local legend.

The Australian environment is unforgiving. These cow types in Australia aren't just a list of names; they are a map of our geography. We’ve bred animals to fit the land, rather than trying to force the land to fit the animals. It’s a delicate balance of genetics, exports, and sheer stubbornness.

Actionable Insights for the Consumer

If you want to support the best of Australian cattle production, look for specific breed certifications. "Certified Angus Beef" (CAB) is a real thing with strict quality controls. If you want something unique, seek out a local butcher who sources Murray Grey—the meat is often finer-grained and incredibly tender without the massive price tag of Wagyu.

For the home cook, remember that Brahman-cross beef (often called "Northern Beef") is leaner. It’s great for slow cooking, stews, or stir-fries where you’re adding moisture. If you’re throwing a steak on a scorching hot BBQ, stick to the southern British breeds like Angus or Hereford; that extra fat is your insurance policy against a dry, tough dinner.

Understand where your food comes from. It’s not just "beef." It’s a Hereford from the New England high country or a Brahman-cross from the Gulf of Carpentaria. Each has a story, and each tastes different because of the life it led and the genes it carried.

Next Steps for Deepening Your Knowledge:

- Check the MSA Grade: Look for the Meat Standards Australia (MSA) symbol on packaging. This isn't a breed, but a grading system that accounts for breed, age, and handling to guarantee tenderness.

- Visit a Local Agricultural Show: If you're in a rural area during show season, head to the cattle pavilions. It’s the best way to see a Charolais (huge, white, muscular French breed) next to a Limousin and see the scale of these animals in person.

- Read the Label: Start noticing if your milk is "A2." This refers to a specific protein type found more commonly in certain breeds like Guernseys and Jerseys, which some people find easier to digest than the A1 protein found in most Holstein-Friesian milk.