You’re breathing right now. It feels automatic. Your chest expands, your ribs lift, and then everything settles back down. But have you ever stopped to think about what makes that flexibility possible? If your rib cage were made entirely of solid bone, you’d basically be encased in a suit of armor that wouldn't let you take a deep breath without cracking. This is where your costal cartilage comes in. It’s the unsung hero of the thoracic cage.

When people ask costal cartilages are composed of what tissue, they usually expect a one-word answer. Honestly, the quick answer is hyaline cartilage. But saying it’s just hyaline cartilage is like saying a Ferrari is just "metal." There is a world of microscopic complexity happening between your ribs and your sternum that keeps you alive.

The Glassy Truth: Hyaline Cartilage

Hyaline cartilage is the specific stuff. The word "hyaline" actually comes from the Greek word hyalos, which means glass. If you were to look at a fresh sample of costal cartilage under a microscope without any fancy dyes, it would look pearly, translucent, and—you guessed it—glassy.

This tissue is surprisingly simple yet incredibly durable. Unlike your skin or your liver, this tissue doesn't have a bunch of blood vessels running through it. It’s avascular. This means the cells living inside that cartilage, called chondrocytes, have to get their nutrients through a slow process of diffusion from the surrounding fluids. This is why when you injure your rib cartilage, it takes forever to heal. There’s no high-speed blood highway delivering repair crews to the site.

The matrix of costal cartilage is a dense soup of Type II collagen fibers and proteoglycans. Think of collagen as the "rebar" in concrete. It provides the tensile strength. The proteoglycans act like a sponge, soaking up water to provide that bouncy, compressive strength that allows your chest to absorb a blow without your ribs snapping like dry twigs.

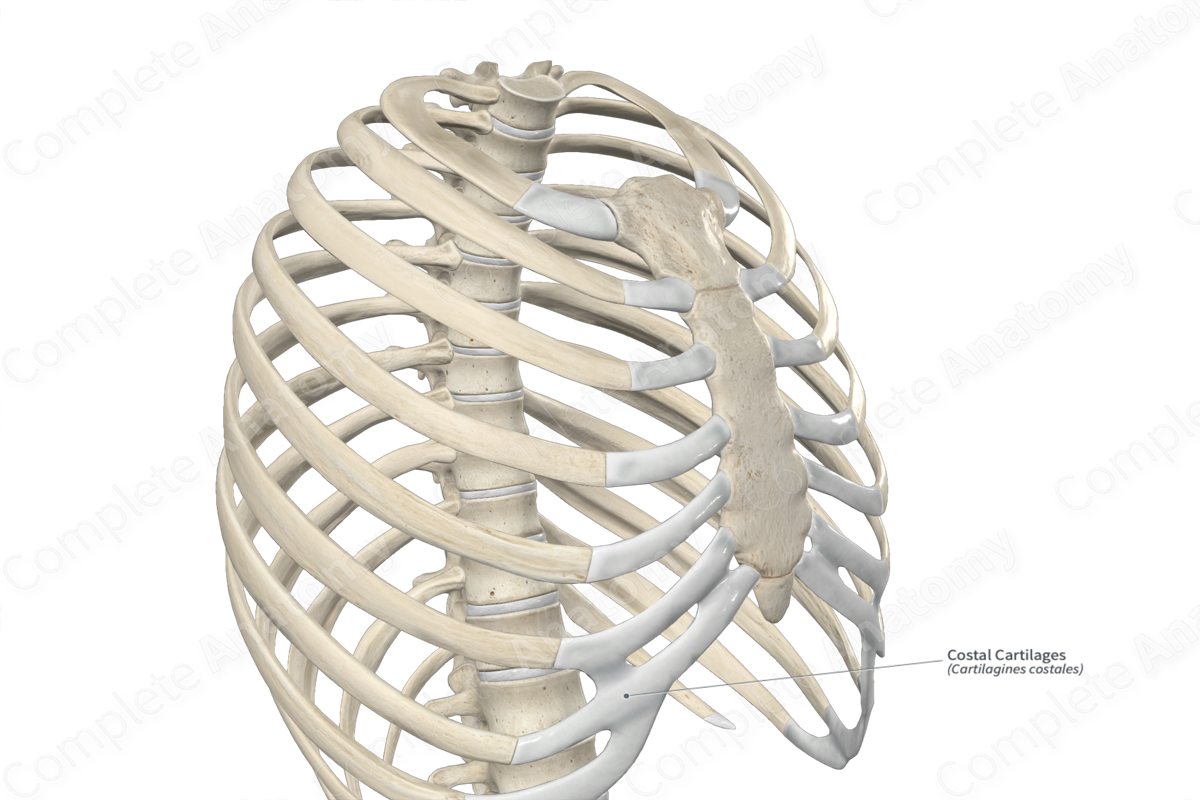

Why Your Ribs Aren't Just Bone

If you’ve ever felt the area where your ribs meet your breastbone, you’ve felt this tissue. It’s firm. It’s not squishy like your earlobe, which is made of elastic cartilage. It's much tougher. But it’s also not rigid like the femur in your leg.

Evolutionary biology is pretty smart here. If the entire thoracic cage were bone, the act of breathing would require a massive amount of muscular force to deform the bone, or we’d need complex mechanical hinges at every single connection point. Instead, we have these bars of hyaline cartilage. They act as "torsion bars." When you inhale, these cartilages actually twist slightly. When you exhale, they "spring" back to their original shape.

🔗 Read more: No Alcohol 6 Weeks: The Brutally Honest Truth About What Actually Changes

Basically, your breathing is partly powered by the elastic recoil of this tissue.

The Seven-Three-Two Split

Not all costal cartilages are created equal. You’ve got twelve pairs of ribs, but they don't all use their cartilage in the same way.

The first seven pairs are the "true" ribs. Their costal cartilages attach directly to the sternum. Then you have the "false" ribs (8, 9, and 10), which don't have their own private connection to the breastbone. Instead, their cartilages hitch a ride and attach to the cartilage of the rib above them. This creates that curved "costal margin" you can feel at the bottom of your rib cage. Finally, the floating ribs (11 and 12) have tiny caps of costal cartilage that just end in the muscle of the abdominal wall.

What Happens When the Tissue Changes?

Here is something most people get wrong: they think cartilage stays the same forever. It doesn't.

As you get older, your costal cartilages undergo a process called calcification. This is essentially the deposition of calcium salts within the hyaline matrix. It’s not turning into true bone—it doesn't have the organized "osteon" structure of bone—but it becomes much harder and more brittle.

Medical professionals, especially radiologists, see this all the time on X-rays. In a young person, costal cartilage is invisible on a standard X-ray because it’s not dense enough to block the beams. In an older adult, you’ll see these white, patchy "ghosts" where the ribs meet the sternum. That’s calcified cartilage. It’s a normal part of aging, but it’s also why older people might find it slightly harder to take those massive, deep breaths; their chest wall just isn't as springy as it used to be.

💡 You might also like: The Human Heart: Why We Get So Much Wrong About How It Works

Tietze Syndrome and Costochondritis

Because costal cartilages are composed of what tissue (that avascular hyaline stuff), they are prone to specific types of inflammation. You might have heard of costochondritis. It sounds scary, but it’s basically just inflammation of the junction where the rib bone meets the cartilage.

Since the tissue doesn't have a direct blood supply, the inflammatory process can be stubborn. It causes sharp chest pain that often mimics a heart attack, which sends a lot of people to the ER in a panic. The difference? If you press on the cartilage and it hurts, it’s likely costochondritis. You can't "press" on a heart attack.

Tietze Syndrome is a rarer cousin of this, where the cartilage actually swells up enough to be visible. Because hyaline cartilage is so dense, when it swells, it really has nowhere to go, which is why it can be so incredibly painful.

Microscopic Anatomy: The Perichondrium

Wrapping around these bars of cartilage is a fibrous "skin" called the perichondrium. This is actually where the limited life support comes from. The perichondrium has two layers:

- An outer fibrous layer (for protection).

- An inner chondrogenic layer (where new cartilage cells are born).

If you’re a surgeon performing a rib graft—say, to reconstruct a nose or an ear—you have to be very careful with this layer. If you leave the perichondrium intact at the donor site, the body can sometimes actually regrow the costal cartilage you removed. Nature is wild.

Clinical Realities and Trauma

In the world of forensic science and trauma surgery, costal cartilage is a major tell-tale sign. Because it’s more flexible than bone, it can absorb a lot of energy. However, in high-impact accidents, like a car crash where the chest hits the steering wheel, the cartilage can "fracture" or tear away from the bone (a costochondral separation).

📖 Related: Ankle Stretches for Runners: What Most People Get Wrong About Mobility

Unlike a bone fracture, which heals with a "callus" of new bone, a cartilage tear often heals with a "fibrous union." This is essentially internal scar tissue. It’s functional, but it’s never quite as strong or as flexible as the original hyaline tissue.

Actionable Insights for Rib Health

If you're dealing with pain in the area where your costal cartilages live, or you just want to keep your thoracic cage healthy, keep these things in mind:

- Work on Thoracic Mobility. Since costal cartilage calcifies with age, doing gentle twisting and stretching exercises helps maintain the "play" in those joints. If you don't use the range of motion, you lose it faster.

- Anti-inflammatory Diet. Because costochondritis is an inflammatory issue of the hyaline tissue, things like Omega-3 fatty acids (found in fish oil) can actually help manage the "simmering" irritation in those junctions.

- Posture Matters. If you slouch constantly, you’re putting your costal cartilages in a "compressed" state. Over years, this can lead to permanent changes in the shape of the thoracic cage and limit your lung capacity.

- Vitamin D and K2. While these are famous for bone health, they are also critical for regulating where calcium goes in the body. You want calcium in your bones, not necessarily depositing early in your costal cartilages.

The next time you take a deep breath, give a little thanks to that "glassy" tissue holding your chest together. It’s a lot more than just a connector; it’s the mechanical spring that keeps you breathing without even trying.

References and Expert Sources:

- Gray's Anatomy: The Anatomical Basis of Clinical Practice.

- Dr. Robert Meislin, Orthopedic Specialist, on the recovery of avascular tissues.

- Journal of Anatomy, "Calcification patterns in costal cartilage."

- The Thoracic Surgeon’s Guide to the Chest Wall, Springer Publishing.

To better understand the mechanical stress on these tissues, you could look into the "pump handle" and "bucket handle" motions of the ribs during respiration.