Light is weird. It doesn't just travel in straight lines and call it a day; it bounces, slows down, and curves depending on what it hits. If you've ever looked into the back of a metal spoon or struggled to read the tiny print on a medicine bottle, you’ve played with the physics of a convex lens and concave mirror. Most people think of them as opposites. One is a piece of glass you look through, and the other is a shiny surface you look at. But here’s the kicker: mathematically and functionally, they are practically twins.

They both converge light. They both bring rays together to a single point.

If you understand how one works, you basically understand the other. It’s all about the "converging" power. While a flat window let’s light pass through without much fuss, these curved tools force light to cooperate, creating images that can be tiny, massive, upright, or upside down.

The Physics of Bringing It All Together

Let’s talk about convergence. When we say a convex lens and concave mirror are converging systems, we mean they take parallel light rays—like the ones coming from a distant star or a flashlight—and bend them toward a common focal point.

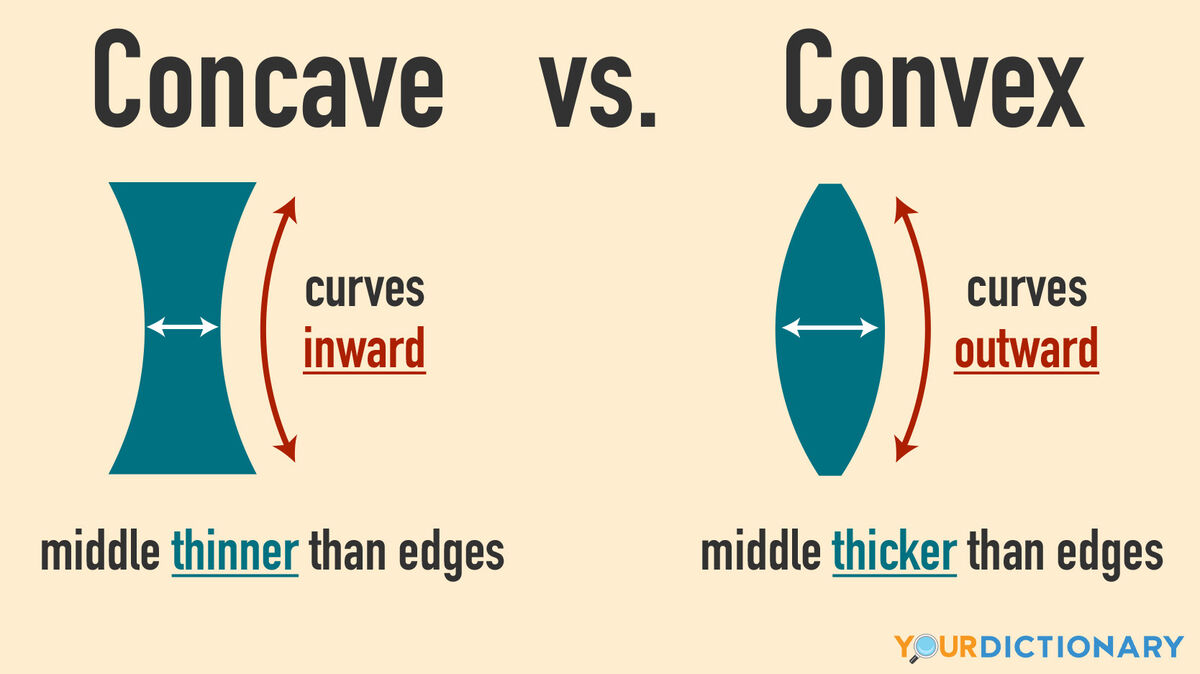

A convex lens is thicker in the middle than at the edges. Think of it like a lentil. In fact, the word "lens" comes from the Latin word for lentil. When light enters the glass, it slows down. Because the middle is thicker, the light hitting the center stays straight, but the light hitting the curved edges gets bent inward. This is refraction.

A concave mirror does the same thing but through reflection. It’s shaped like a cave—hence the name. When light hits that silvered, receding surface, the angles of the curve force the light to bounce back toward the center.

It’s actually pretty cool.

Whether the light is passing through glass or bouncing off a mirror, the result is a real image. In physics-speak, a "real" image is one you can actually project onto a screen. You can’t do that with a flat bathroom mirror. If you try to project your reflection from a flat mirror onto a piece of paper, you’ll just get a blob of light. But with a concave mirror or a convex lens? You can literally project a movie onto a wall.

Why Your Eyes and Cameras Depend on Convex Lenses

You’re using a convex lens right now.

Inside your eye, sitting just behind the pupil, is a flexible convex lens. Its job is to take the light bouncing off this screen and focus it perfectly onto your retina. If that lens doesn't curve enough, or if it curves too much, things get blurry. That’s where glasses come in.

📖 Related: 20 Divided by 21: Why This Decimal Is Weirder Than You Think

But it’s not just biology. Take a look at a high-end DSLR camera. Inside that massive lens housing isn't just one piece of glass. It’s a "compound lens" system, but the star of the show is almost always a series of convex elements. They take a wide landscape—maybe a mountain range—and shrink it down to fit on a tiny digital sensor.

Real-world magnifying power

Ever used a magnifying glass to look at an ant or fry a leaf? (Hopefully just the ant-watching part). That’s a simple convex lens. When you hold it close to an object, it creates a "virtual image." The light rays spread out in a way that tricks your brain into thinking the object is much larger than it actually is.

But there is a limit.

If you move the magnifying glass too far away, the image flips upside down. Suddenly, the ant is standing on its head. This happens because you’ve moved the object past the "focal point." It’s a hard limit of physics. Once the light rays cross that point, they start spreading out again, but inverted.

The Concave Mirror: From Shaving to Satellites

If you want to see how a concave mirror works without buying lab equipment, go to your bathroom. Or your vanity. Makeup mirrors and shaving mirrors are almost always concave.

Why? Because they magnify.

When you get your face close to a concave mirror—staying inside that focal length—you see a right-side-up, enlarged version of yourself. It’s perfect for seeing exactly where that eyeliner is going. But just like the magnifying glass, if you back away from the mirror, you’ll eventually reach a "dead zone" where everything is a blur, and then—pop—you’re upside down.

Solar Ovens and Death Rays

Concave mirrors are also masters of heat. Because they take all the energy from a large surface area and cram it into one tiny point, they can generate intense temperatures.

- Solar furnaces use giant arrays of concave mirrors to melt steel.

- Back in the day, legend has it that Archimedes used "burning mirrors" to set fire to Roman ships by focusing sunlight on them. While MythBusters had a hard time replicating it perfectly, the math is sound.

- Satellite dishes aren't mirrors for light, but they are mirrors for radio waves. They use that same concave "dish" shape to catch weak signals from space and bounce them onto the receiver (the LNB) sitting out on that little arm in the middle.

The Math That Connects Them

You don’t need to be a mathematician to get the gist, but there is one formula that rules them both. It’s the Mirror and Lens Equation:

👉 See also: When Can I Pre Order iPhone 16 Pro Max: What Most People Get Wrong

$$\frac{1}{f} = \frac{1}{d_o} + \frac{1}{d_i}$$

Here, $f$ is the focal length, $d_o$ is the distance to the object, and $d_i$ is the distance to the image.

The weird thing is that this formula works for both a convex lens and concave mirror. The only difference is how you handle the signs (positive or negative). In a convex lens, the focal length is positive because it's "converging." In a concave mirror, it’s also positive.

This symmetry is why scientists treat them as two sides of the same coin. They are the "positive" optical elements. Their opposites—the concave lens and convex mirror—are the "negative" elements that spread light out.

Where People Get Confused (The "Objects in Mirror" Problem)

You know that warning on your car’s side-view mirror? "Objects in mirror are closer than they appear."

That is NOT a concave mirror. That’s a convex mirror.

It’s easy to get the names flipped. A concave mirror curves inward like a bowl. A convex mirror bulges out like a ball.

A concave mirror is great for detail, but it has a very narrow field of view. You can see your eye really well, but you can’t see the rest of the room. A convex mirror (like on your car or the security mirrors in a convenience store) does the opposite. It shrinks everything so it can fit a massive, wide-angle view into a small space.

It’s the trade-off of optics: you can have magnification, or you can have a wide field of view. You can't have both at the same time with a single element.

✨ Don't miss: Why Your 3-in-1 Wireless Charging Station Probably Isn't Reaching Its Full Potential

Telescopes: The Ultimate Partnership

If you want to see the rings of Saturn, you need both reflection and refraction.

Back in the 1600s, Isaac Newton got annoyed with convex lenses. Early lenses had a problem called "chromatic aberration." Basically, they acted like prisms and split light into rainbows, making stars look like colorful blurs.

Newton’s solution? Use a concave mirror instead of a lens to gather the light.

Since mirrors reflect all colors of light the same way, the "rainbow blur" disappeared. This gave birth to the Reflecting Telescope. Today, every major observatory on Earth—and the James Webb Space Telescope out in deep space—uses a massive concave mirror to see the beginning of time.

The James Webb doesn't use glass you look through. It uses 18 gold-plated hexagonal beryllium segments arranged in a massive concave shape. It’s basically the world’s most expensive makeup mirror, staring at the infrared glow of distant galaxies.

Nuance and Limitations: It’s Not Always Perfect

No lens or mirror is perfect. Even the best convex lens and concave mirror suffer from something called "spherical aberration."

When you make a lens or mirror in a perfect spherical curve (like a slice of a ball), the light at the very edges doesn't focus at exactly the same spot as the light in the middle. This creates a slightly fuzzy image.

To fix this, engineers have to create "aspheric" shapes. These are curves that are just a tiny bit "off" from a perfect circle. Manufacturing these is way harder and way more expensive. If you’ve ever wondered why a high-end camera lens costs $2,000 while a cheap one costs $100, the quality of the aspheric grinding is usually why.

Actionable Steps for Using These Optics

If you’re a hobbyist, a student, or just curious, you can actually use this knowledge to manipulate light at home.

- Determine Focal Length: Take a convex lens (like a magnifying glass) on a sunny day. Move it back and forth over a sidewalk until the point of light is as small and sharp as possible. The distance from the glass to the sidewalk is your focal length.

- Identify Your Mirrors: If you aren't sure if a mirror is concave or convex, put your finger close to it. If your finger looks giant, it's concave. If your finger looks tiny and you can see the whole room behind you, it's convex.

- DIY Projector: You can actually turn an old smartphone and a convex lens into a movie projector. By placing the phone at the right distance behind the lens, you can project your screen onto a white sheet. Just remember: the image will be upside down, so you have to lock your phone's screen rotation and flip the phone itself!

- Check Your Glasses: If you’re nearsighted, your glasses are actually concave lenses (the opposite of what we've focused on here). If you’re farsighted or need "readers," you’re rocking convex lenses.

The world of optics isn't just for lab coats. It's in your pocket, on your face, and in the headlights of your car. Understanding how a convex lens and concave mirror manipulate the path of a photon is basically like learning a magic trick that the entire universe is in on.

For your next step, try the "spoon trick." Look at the inside of a polished metal spoon. That’s your concave mirror. Slowly move it toward your eye. Watch the exact moment your reflection flips from upside down to right-side up. That "flip" is you passing through the focal point, the exact spot where physics turns the world on its head.