You’re standing on a scale. It says 70. You call that your weight. Honestly, you’re wrong. Scientifically speaking, anyway. What you’re actually measuring is mass, but the scale is doing a bunch of invisible math behind the glass to keep you from having to think about physics. If you ever find yourself staring at a physics problem or a piece of industrial equipment calibrated in Newtons, you’ve probably realized that converting Newtons to kilograms isn't just about moving a decimal point. It’s about gravity.

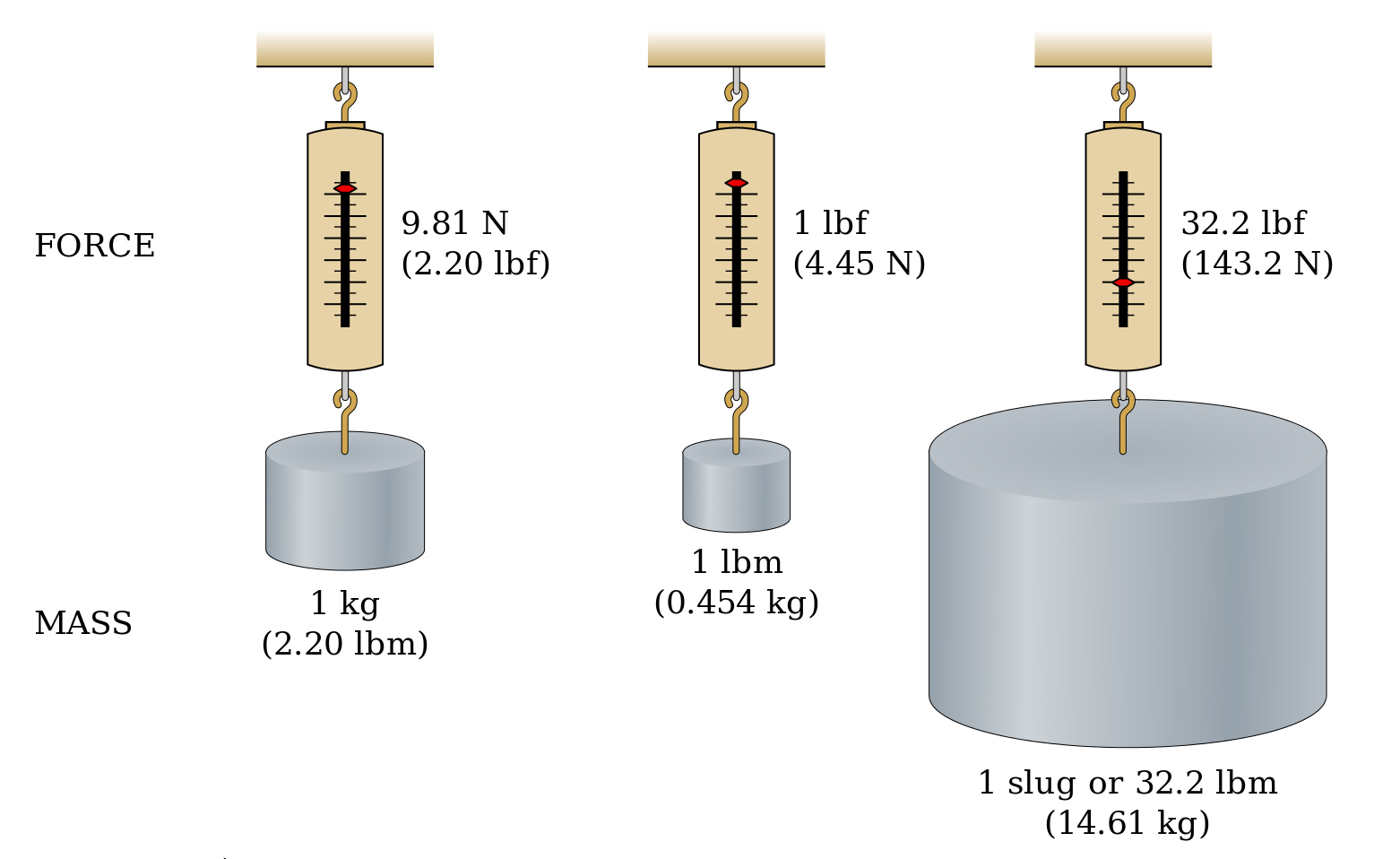

Most people get Newtons and kilograms mixed up because we live in a world where Earth's gravity is basically a constant. We treat them like they’re the same thing. They aren't. A Newton (N) is a unit of force. A kilogram (kg) is a unit of mass. Mass is how much "stuff" is in you. Force is how hard that "stuff" is being pulled toward the floor.

The Math Behind Converting Newtons to Kilograms

Here is the thing. To get from Newtons to kilograms, you have to divide. Specifically, you divide the force in Newtons by the acceleration due to gravity. On Earth, that number is roughly 9.80665 meters per second squared.

Most people just round it to 9.8. If you’re doing quick math in your head and don't care about being hyper-accurate, 10 works too. But if you're an engineer or a student, stick to 9.8. The formula looks like this:

$$m = \frac{F}{g}$$

In this scenario, $m$ is your mass in kilograms, $F$ is the force in Newtons, and $g$ is gravity. If you have 100 Newtons, you divide that by 9.8. You get roughly 10.2 kilograms. Simple? Yeah, sort of. But there is a catch.

Why Gravity Changes the Equation

Gravity isn't the same everywhere. It's weird to think about, but you actually weigh slightly less at the equator than you do at the North Pole. Why? Because the Earth isn't a perfect sphere; it's a bit fat in the middle. Centrifugal force from the Earth's rotation also pushes you "out" a bit at the equator, fighting gravity.

If you were on the Moon, converting Newtons to kilograms would require a totally different divisor. Moon gravity is about 1.62 $m/s^2$. Your mass (kilograms) stays the same, but the force (Newtons) drops significantly. This is why astronauts bounce. Their mass hasn't changed—their inertia is still the same—but the force pulling them down is weak.

Real-World Examples of the Conversion

Let’s look at a few common objects. A medium-sized apple weighs roughly 1 Newton. It’s actually where the name comes from—the legend of the apple falling on Isaac Newton's head. To find the mass of that apple in kilograms, you'd take 1 and divide it by 9.8. You get 0.102 kg, or about 102 grams.

What about a person? If a sensor tells you that you are exerting 686 Newtons of force on the ground, you divide 686 by 9.8. You get exactly 70 kilograms.

Why This Matters in Technology and Engineering

In the world of aerospace or mechanical engineering, getting this wrong is a disaster. Imagine you're designing a drone. You need to know how much lift the motors need to generate. Lift is measured in Newtons. But the battery, the frame, and the camera are all sold by their mass in kilograms.

If you just assume 1 kg equals 1 Newton, your drone isn't going anywhere. It won't even lift off the grass. You need about 9.8 Newtons of lift just to hover a 1 kg drone. Actually, you need more than that to actually move upward.

The Confusion with "Kilogram-Force"

There is this old-school unit called "kilogram-force" (kgf). It was invented specifically to make people's lives easier, and instead, it made everything more confusing. One kilogram-force is exactly the amount of force exerted by one kilogram of mass in standard Earth gravity.

So, 1 kgf = 9.80665 N.

A lot of old torque wrenches or hydraulic presses still use kgf. If you see a label that says "10 kg," but it's on a pressure gauge or a force sensor, it’s probably talking about kgf. To get to Newtons, you multiply by 9.8. To get back to the actual mass in kilograms, well, if the gravity is standard, it’s a 1:1 ratio. But don't rely on that if you're working in a lab.

Common Mistakes When Converting Newtons to Kilograms

One of the biggest blunders is forgetting that Newtons can represent forces other than gravity. If you’re pushing a car horizontally, you’re applying Newtons of force. But that force isn't "weight." You can't just divide that horizontal push by 9.8 to find the mass of the car. That would give you a meaningless number.

To find mass using horizontal force, you'd need to know the acceleration. This is Newton's Second Law: $F = ma$.

- Mistake 1: Using 9.8 for objects not on Earth.

- Mistake 2: Thinking mass changes when you go to high altitudes. (It doesn't, but Newtons do).

- Mistake 3: Mixing up Newtons with Joules. (Joules is energy, Newtons is force).

If you are at the top of Mount Everest, $g$ is about 9.77 $m/s^2$. It’s a tiny difference, but for high-precision instruments, it’s enough to throw off a calibration. Scales used in scientific research actually have to be calibrated to the specific latitude and altitude of the lab where they are being used.

How to Calculate This on the Fly

If you don't have a calculator, use the "Rule of Ten." It’s a classic physics student trick.

- Take your Newtons.

- Knock off the last digit (essentially dividing by 10).

- The result is your mass in kilograms, slightly underestimated.

Example: 500 Newtons. Knock off a zero. 50 kg.

The real answer (500 / 9.8) is 51.02 kg. For most casual conversations, 50 is close enough.

The Origin Story: Isaac Newton and the SI System

We use the Newton because of the International System of Units (SI). Before the Newton was adopted in 1946 by the General Conference on Weights and Measures (CGPM), force was measured in all sorts of messy ways. The "dyne" was popular for a while. One dyne is much smaller—it's the force needed to accelerate one gram at a rate of one centimeter per second squared.

💡 You might also like: Sonos and Apple HomeKit: Why Your Setup Keeps Breaking (and How to Fix It)

Can you imagine doing construction math with dynes? It would be a nightmare. The Newton brought everything into a scale that makes sense for human beings.

Actionable Steps for Accurate Conversion

If you need to be precise, follow these steps:

- Identify the Local Gravity: If you’re in a standard environment, use $9.80665$. If you’re in a specific location like Mexico City (high altitude) or Oslo, look up the local $g$ value.

- Isolate the Force: Ensure the Newton value you have is strictly the gravitational force (weight) and doesn't include other vectors like wind resistance or tension from a rope.

- Perform the Division: Use a calculator. Mental math is great for estimates, but $9.8$ is a clunky number for most brains.

- Check Your Units: Ensure your result is in kg. If you need grams, multiply your final answer by 1,000.

For those working in digital spaces, many CAD (Computer-Aided Design) programs like SolidWorks or AutoCAD handle these conversions automatically. However, you still have to input the correct material density so the software knows the mass before it calculates the force (weight) in a simulation.

Always double-check if the "Newtons" you are looking at are "Peak Force" or "Static Force." In a car crash test, for example, the Newtons measured are the impact force, which is way higher than the weight of the car. If you tried to convert the impact Newtons of a crashing car into kilograms, you'd get a mass that suggests the car weighs as much as a blue whale. Context is everything.

To keep your calculations consistent, always convert all your measurements to the SI base units (meters, kilograms, seconds) before you start dividing or multiplying. This prevents "unit soup," where you accidentally end up with a result that is off by a factor of ten or a hundred. If you have kilonewtons (kN), remember to multiply by 1,000 first to get back to standard Newtons before you divide by 9.8.