You're looking at a tiny speck. Maybe it's a grain of sand or a microscopic component in a high-end smartphone. You measure it in cubic millimeters ($mm^3$). But then, your boss or your lab manual asks for the volume in cubic meters ($m^3$). Suddenly, the numbers don't feel right. You divide by a thousand because, hey, there are a thousand millimeters in a meter, right?

Wrong. If you do that, your calculation is going to be off by a factor of a million. It’s a classic mistake. I see it in engineering labs and undergrad physics classrooms all the time. People forget that when you move into the third dimension, the math doesn't just scale linearly—it explodes.

The leap from mm cubed to m cubed is massive. We are talking about nine decimal places. If you’re designing a precision cooling system for a data center or calculating the displacement of a microfluidic chip, getting this wrong isn't just a "minor oopsie." It’s the difference between a functional product and a catastrophic failure that costs thousands of dollars in wasted materials.

The Mental Trap of Linear Thinking

Most of us have the metric system's linear scale burned into our brains. 1,000 millimeters equals 1 meter. Simple. But volume isn't a line. It’s a space.

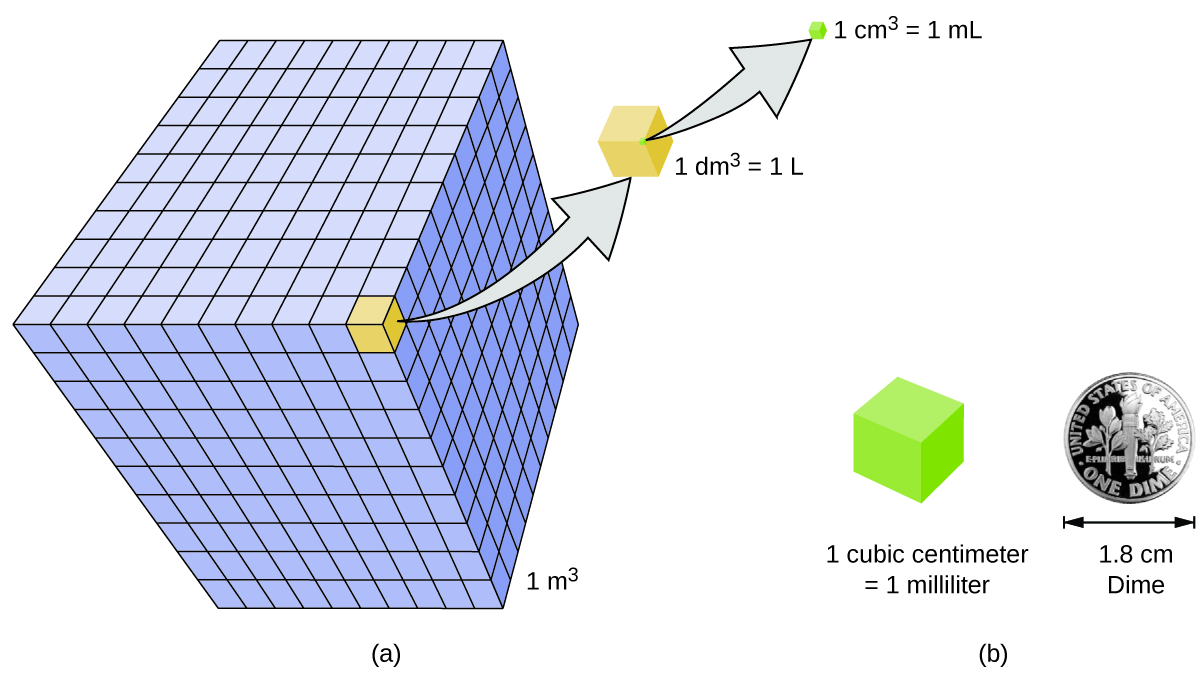

Think of a cube. If that cube is one meter tall, one meter wide, and one meter deep, you have one cubic meter. Now, try to pack that same space with tiny cubes that are only one millimeter on each side. You aren't just putting 1,000 of them in there. You have to layer them.

You need 1,000 of those tiny cubes just to make a single line. Then you need 1,000 of those lines to cover the floor of your big meter cube. That’s already 1,000,000 tiny cubes just to cover the bottom surface! But you aren't done. You have to stack those layers 1,000 high to reach the top.

$$1,000 \times 1,000 \times 1,000 = 1,000,000,000$$

That’s one billion.

💡 You might also like: Why the Grumman LLV Mail Truck Refuses to Die

Honestly, it’s hard to visualize a billion of anything. If you had a billion cubic millimeter beads, they would fill a standard shipping crate. This is why the conversion from mm cubed to m cubed feels so counterintuitive. Your brain wants it to be a smaller jump, but the physics of 3D space demands a billion-fold difference.

The Formula You Actually Need

Forget the "move the decimal point" tricks for a second and just look at the raw math. To convert cubic millimeters to cubic meters, you divide the value by 1,000,000,000.

In scientific notation, which is what any real pro uses to avoid losing track of all those zeros, the conversion factor is $10^{-9}$.

$$V_{m^3} = V_{mm^3} \times 10^{-9}$$

Or, if you prefer decimals:

$$1 mm^3 = 0.000000001 m^3$$

If you’re working in CAD software like SolidWorks or AutoCAD, you might find that the system handles this for you, but you still have to set the base units correctly. I’ve seen projects where someone imported a part designed in mm into a workspace set to meters without checking the scale. Suddenly, a bracket meant to hold a sensor becomes the size of a skyscraper in the simulation. It’s a mess.

Real World Example: Micro-Manufacturing

Let’s look at something real. High-precision 3D printing, specifically Two-Photon Polymerization (TPP). Companies like Nanoscribe produce parts where the total volume might be 5,000 cubic millimeters. That sounds like a decent amount, right?

But when you convert that 5,000 mm cubed to m cubed for a bulk material order or a shipping density calculation, you get $0.000005 m^3$.

That number is so small it’s almost meaningless in a macro context. This is why specialized industries often stick to $mm^3$ or even $microns^3$. Shifting to $m^3$ too early in the design process leads to rounding errors that can ruin your precision.

Why This Conversion Trips Up the Best Engineers

Even if you know the math, the way we talk about units is confusing. We say "cubic millimeter," but we write it as $mm^3$. The exponent is on the unit, not the number.

If you have $2 mm$, and you want to cube it, you get $8 mm^3$.

But if you have a volume already labeled as $2 mm^3$, and you want to convert it to meters, you don't cube the 2. You only apply the conversion factor of the units.

It’s a linguistic trap.

I once worked with a mechanical engineer who was calculating the volume of a proprietary polymer resin needed for a micro-molding run. He had the volume in cubic millimeters. He divided by $1,000^2$ instead of $1,000^3$. He ended up ordering 1,000 times more resin than the cleanroom actually needed. It was a $12,000 mistake. All because of one missing power of ten.

Navigating the Metric Scale

The metric system is beautiful because it’s logical, but it’s also unforgiving. When you’re jumping between scales, you’re basically moving through different worlds.

- The Micro World: $mm^3$ is perfect for electronics, jewelry, and medical devices.

- The Human World: $cm^3$ (or milliliters) is what we use for medicine doses or a can of soda.

- The Industrial World: $m^3$ is for concrete, water reservoirs, and cargo space.

Trying to use $m^3$ to describe the volume of an LED is like trying to measure the length of a ladybug in miles. It’s technically possible, but the number is so small it becomes useless for daily work.

However, when you're doing "big picture" physics—calculating buoyancy in a tank or the mass of a large shipment based on density—you must get back to the SI base unit of $m^3$. Most density constants, like the density of water ($1,000 kg/m^3$), are tied to the cubic meter. If you plug $mm^3$ into a formula expecting $m^3$, your results won't just be slightly off. They will be "blow up the lab" off.

Practical Steps for Error-Free Conversion

Don't trust your head. Don't even trust a quick mental decimal shift.

- Write the number down in scientific notation. If you have 450,000 $mm^3$, write $4.5 \times 10^5 mm^3$.

- Multiply by the conversion factor: $10^{-9}$.

- Add the exponents: $5 + (-9) = -4$.

- Your result is $4.5 \times 10^{-4} m^3$.

This method is bulletproof. It works every time, whether you're a student or a senior lead at SpaceX.

Another pro tip: check the "sanity" of your number. If you are converting a small volume from mm cubed to m cubed, the resulting number should be tiny. If you end up with a number larger than what you started with, you multiplied when you should have divided. It sounds obvious, but in the middle of a high-stress project, these are the exact errors that slip through.

If you're working in a digital environment, use a dedicated unit conversion tool or a verified spreadsheet template. Most scientific calculators have a "CONV" function—use it.

Dealing with Complex Densities

Sometimes the conversion is just the first step. If you’re calculating the weight of a part, you’ll likely have a density in grams per cubic centimeter ($g/cm^3$).

Now you've got three different units in one problem: $mm^3$, $cm^3$, and $m^3$.

The best way to handle this is to bring everything to the cubic meter first. It’s the "home base" of the International System of Units. Once everything is in $m^3$, the math becomes a straight line. No more jumping through hoops.

Final Actionable Insights

To keep your projects on track and your math accurate, follow these rules of thumb:

Always verify if the value you are looking at is a length ($mm$) that needs to be cubed, or a volume ($mm^3$) that is already cubed.

When moving from mm cubed to m cubed, remember the "Rule of Nine." You are moving the decimal point nine places to the left. If you don't have enough digits, fill them with zeros.

For any professional documentation, use scientific notation ($1 \times 10^{-9}$) to represent the conversion. It eliminates the risk of someone miscounting the zeros in $0.000000001$.

Double-check your software’s default units. Most CAD errors happen at the "Import" stage because the user assumes the software "knows" what the units are. It doesn't.

If you follow these steps, you’ll avoid the common pitfalls that plague everyone from hobbyists to professional engineers. Accurate volume conversion is about more than just numbers; it's about ensuring the physical integrity of whatever you are building or measuring.