You're standing outside, or maybe you're checking a digital thermometer while traveling abroad, and you see it: 35°C. For Americans used to the Fahrenheit scale, that number looks deceptively low. It’s not. In fact, when you convert 35 centigrade to fahrenheit, you land right in the middle of what most people would describe as a "very warm day."

It's exactly 95 degrees Fahrenheit.

💡 You might also like: Why Pumpkin Puree Brownie Mix Is Actually The Best Baking Hack You're Not Using

Think about that for a second. If you’re packing for a trip to Europe or Australia and the forecast says 35, you aren't grabbing a light jacket. You're grabbing extra water and the strongest sunscreen you can find. It’s that weird tipping point where "nice weather" starts to feel a bit oppressive if you're walking around a city all day. Honestly, the math behind it is something most of us forgot the moment we walked out of high school chemistry, but understanding the relationship between these two scales is basically a survival skill in a globalized world.

The Dirty Math: How We Get to 95°F

Most people just want the answer. I get it. But if you’re stuck without a phone and need to figure out 35 centigrade to fahrenheit, you need a mental shortcut. The formal equation is a bit of a clunker:

$$F = (C \times \frac{9}{5}) + 32$$

Basically, you take your Celsius temperature, multiply it by 1.8, and then tack on 32.

Let's walk through it with 35.

35 times 1.8 is 63.

Add 32 to that 63, and you get 95.

If you're like me and hate doing decimals in your head while sweating in the sun, use the "Double and Add 30" rule. It’s a dirty trick, but it works for a quick estimate. Double 35 to get 70. Add 30. You get 100. It’s 5 degrees off, but it tells you immediately that it's "hot" rather than "temperate." That 5-degree margin of error might matter to a scientist at NASA, but for deciding whether to wear shorts, it’s close enough.

Why 35 Degrees Celsius is a Health Benchmark

There is a reason doctors and meteorologists pay close attention to the 35-degree mark. In the world of physiology, 35°C is often cited as a threshold for "heat strain," especially when humidity is high. When the air temperature hits 95°F, it's getting uncomfortably close to your internal body temperature, which usually sits around 98.6°F (37°C).

Once the outside air hits 35°C, your body has a much harder time shedding heat through simple radiation. You become almost entirely dependent on sweat. But here is the kicker: if the humidity is also high, that sweat doesn't evaporate.

The National Weather Service uses something called the Heat Index to explain this. At 35°C (95°F) with 60% humidity, the "feels like" temperature jumps to a staggering 114°F. That’s dangerous. We aren't just talking about being "a little sweaty" anymore; we’re talking about potential heat exhaustion. You’ve got to be careful.

📖 Related: Exactly How Many Fluid Ounces in 1 3 Cup: The Kitchen Math That Saves Your Recipe

The Wet-Bulb Problem

Scientists like those at the NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration) often talk about "wet-bulb" temperatures. This isn't just the reading on your wall; it’s a measure of how much the body can cool down via evaporation. A 35°C wet-bulb temperature is generally considered the limit of human survivability.

Thankfully, a standard 35°C air temperature usually results in a much lower wet-bulb temperature, but the proximity of those numbers is why climate researchers use 35 as a frequent data point in studies about global warming and urban heat islands. When cities hit 35°C, the asphalt and concrete soak up that energy, radiating it back at you long after the sun goes down.

A Global Perspective on 95 Degrees

If you live in Phoenix, Arizona, 95°F (35°C) might actually feel like a "cool front" in July. Context is everything.

In London or Paris, where air conditioning is far from universal, 35°C is a full-blown weather emergency. Most European infrastructure was built to keep heat in, not out. Thick stone walls and lack of ventilation mean that a 35-degree day in London can feel significantly more draining than the same temperature in a climate-controlled American suburb.

I remember being in Rome during a 35°C heatwave. The locals weren't out at noon. They were gone. The "siesta" or "riposo" isn't just a charming cultural quirk; it’s a logical response to the physics of heat. You don't fight 35 degrees. You hide from it.

Common Misconceptions About the Scale

- Linear vs. Non-linear: People often think the scales move together. They don't. A 10-degree jump in Celsius is an 18-degree jump in Fahrenheit. This is why 35°C feels so much hotter than 25°C (77°F).

- The Zero Point: 0°C is freezing, but 0°F is... well, just really cold. The offset of 32 degrees is the most common mistake people make when trying to do the math quickly.

- Centigrade vs. Celsius: For the record, they are the same thing. "Centigrade" was the official name until 1948, derived from the Latin centum (hundred) and gradus (steps). We renamed it to honor Anders Celsius, but the terms are used interchangeably in casual conversation.

35°C in the Kitchen and the Lab

While 35°C is a weather milestone, it shows up in other places too. If you're a baker, 35°C is often the target temperature for "lukewarm" water used to bloom yeast. Much hotter, and you'll kill the organisms; much cooler, and they won't wake up.

In a lab setting, 35°C to 37°C is the standard incubation temperature for many types of bacteria, specifically those that live in or on the human body. It's the "sweet spot" for biological growth. This is why food safety experts warn against leaving perishables out on a 35-degree day. Bacteria can double every 20 minutes in those conditions. That picnic salad becomes a petri dish faster than you can say "salmonella."

Survival Tips for a 35-Degree Day

If you find yourself in a place where the mercury has climbed to 35°C, you need to adjust your behavior. It’s not just about comfort; it’s about safety.

- Pre-hydrate. Don't wait until you're thirsty. By then, you're already behind.

- The Cotton Myth. While cotton is breathable, it holds moisture. In high humidity, a damp cotton shirt can actually stop you from cooling down. Look for moisture-wicking fabrics if you're active.

- Check the "Feels Like." Always look at the dew point or humidity levels. 35°C in the desert is manageable; 35°C in the Everglades is a swampy nightmare.

- Window Management. If you don't have AC, keep your windows closed and curtains drawn during the heat of the day. Open them only at night when the outside air is cooler than the inside air.

Understanding 35 centigrade to fahrenheit is more than just a math problem. It’s about context. It’s the difference between a pleasant walk and a dangerous afternoon. Next time you see that "35" on a screen, remember: 95. It’s hot. Plan accordingly.

Actionable Next Steps:

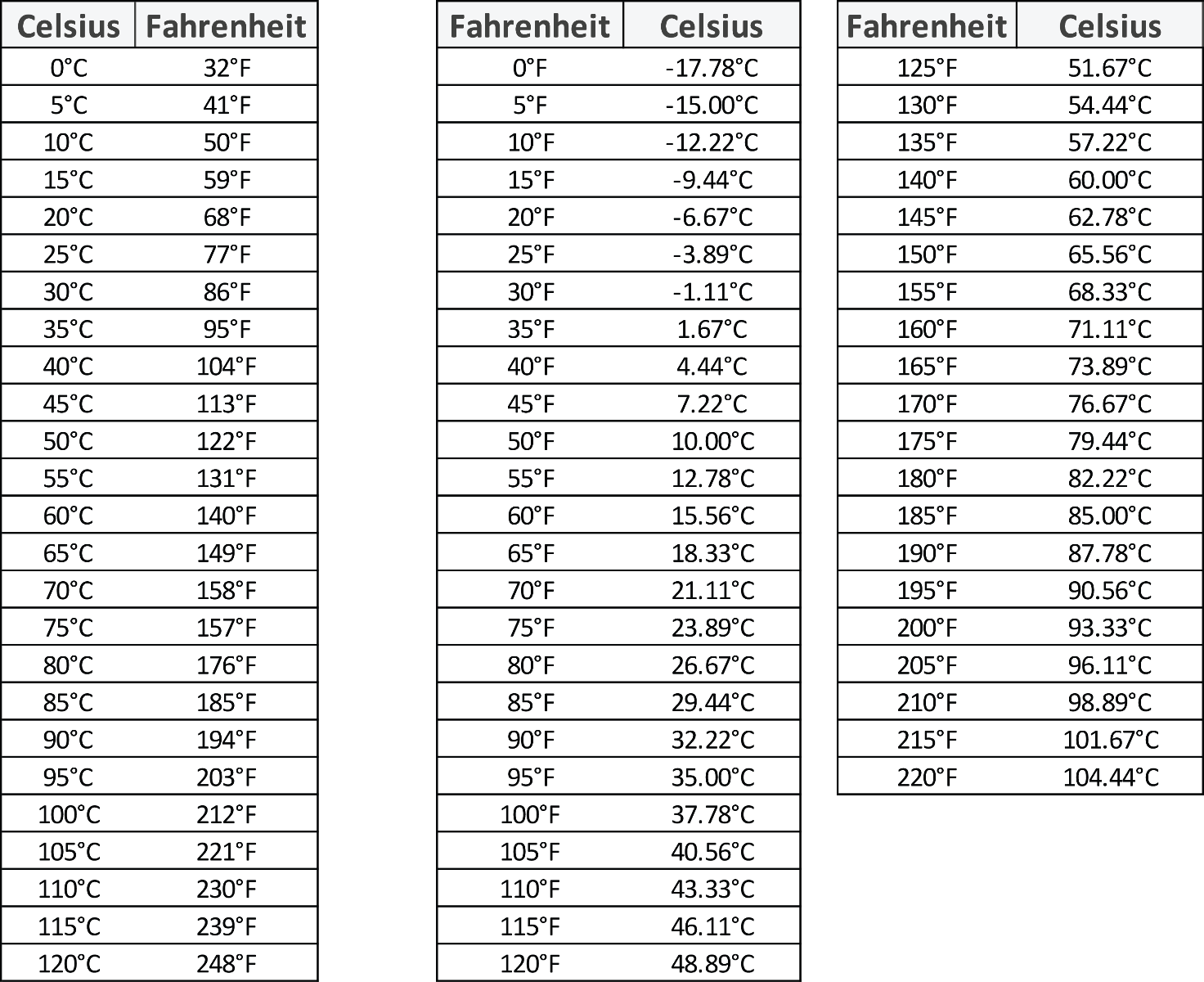

- Download a conversion app or bookmark a reliable table if you frequently communicate with people in different regions.

- Check your home’s insulation and window seals before the summer months to ensure your living space can handle 35°C+ external temperatures.

- Memorize the "30-20-10" rule for quick Celsius-to-Fahrenheit mental shifts: 30°C is 86°F (hot), 20°C is 68°F (room temp), and 10°C is 50°F (chilly). This gives you "anchor points" to estimate any other temperature.

- Monitor the Heat Index, not just the raw temperature, when planning outdoor exercise or manual labor to avoid heat-related illnesses.