You've probably been there. Staring at a string of numbers that stretches out to infinity, wondering if it actually adds up to something or just explodes into a chaotic mess. It’s a classic calculus nightmare. Honestly, the convergence of series test isn't just a hurdle for your midterms; it's the literal backbone of how your calculator figures out the sine of an angle or how Netflix compresses a movie file so it doesn't kill your data plan.

Infinite series are weird. Intuitively, adding up an infinite list of positive numbers should give you an infinite result, right? Not always. Sometimes, those numbers get small fast enough that they "settle" on a specific value. Determining whether that happens is where the magic (and the frustration) of testing for convergence comes in.

The Divergence Test Is Not What You Think

Let’s get one thing straight right away because it’s the biggest trap in real analysis. The $n$-th term test, or the Divergence Test, is a one-way street. If the individual terms of your series don't shrink to zero, the series is toast. It diverges. Period.

But—and this is a massive "but"—just because the terms do go to zero doesn't mean the series converges. Take the Harmonic Series:

$$\sum_{n=1}^{\infty} \frac{1}{n} = 1 + \frac{1}{2} + \frac{1}{3} + \dots$$

The terms get smaller and smaller. They definitely approach zero. Yet, this series is a rebel. It adds up to infinity. It crawls there slowly, sure, but it never stops growing. This is the "false positive" that trips up almost everyone. You see the terms vanishing and assume the sum is finite. Don't fall for it. The Divergence Test can only prove a series is "broken" (divergent); it can never prove a series is "working" (convergent).

Why the Ratio Test is Your Best Friend (Usually)

When you see factorials like $n!$ or powers like $3^n$, you should immediately reach for the Ratio Test. Developed largely through the work of Jean le Rond d'Alembert in the 18th century, this test looks at the "growth rate" between consecutive terms.

💡 You might also like: Why a Cross Section of a Jet Engine Is More Than Just Metal and Fire

Basically, you’re looking at the limit:

$$L = \lim_{n \to \infty} \left| \frac{a_{n+1}}{a_n} \right|$$

If that limit $L$ is less than 1, you're golden. The series converges absolutely. If it’s greater than 1, it’s divergent. But if $L$ equals exactly 1? Total failure. The test is inconclusive, and you've just wasted five minutes of your life. This happens constantly with p-series or rational functions, where the ratio of terms approaches 1 from below, leaving you stuck in mathematical limbo.

The Integral Test and the Ghost of Geometry

Sometimes, algebra fails you. That's when you have to turn to the Integral Test. Think of it as a bridge between the discrete world of sequences and the smooth world of curves. If you can find a continuous, decreasing function $f(x)$ that matches your series terms $a_n$, the area under that curve tells you everything you need to know.

If the integral $\int_{1}^{\infty} f(x) dx$ is finite, the series converges. If the area is infinite, the series diverges. This is exactly how we prove the behavior of p-series. We know $\sum \frac{1}{n^2}$ converges because the integral of $\frac{1}{x^2}$ is finite. It’s elegant, but it requires you to actually be good at integration, which—let’s be real—is its own brand of stress.

There are strict rules here, though. Your function must be positive, continuous, and decreasing. If the terms of your series are oscillating or jumping around, the Integral Test is useless. It’s a tool for steady, predictable decay.

Comparison Tests: The "Buddy System"

Comparison tests are sort of like judging a person by the company they keep. If you have a messy, complicated series, you compare it to a "clean" series that you already understand, like a geometric series or a p-series.

Direct Comparison

This is the most "common sense" test. If your series is smaller than a series that converges, then yours must converge too. If yours is larger than a series that diverges, yours is also headed for infinity. It’s logical. The hard part is finding that "benchmark" series. You need a library of known convergent and divergent series in your head to make this work effectively.

Limit Comparison Test (LCT)

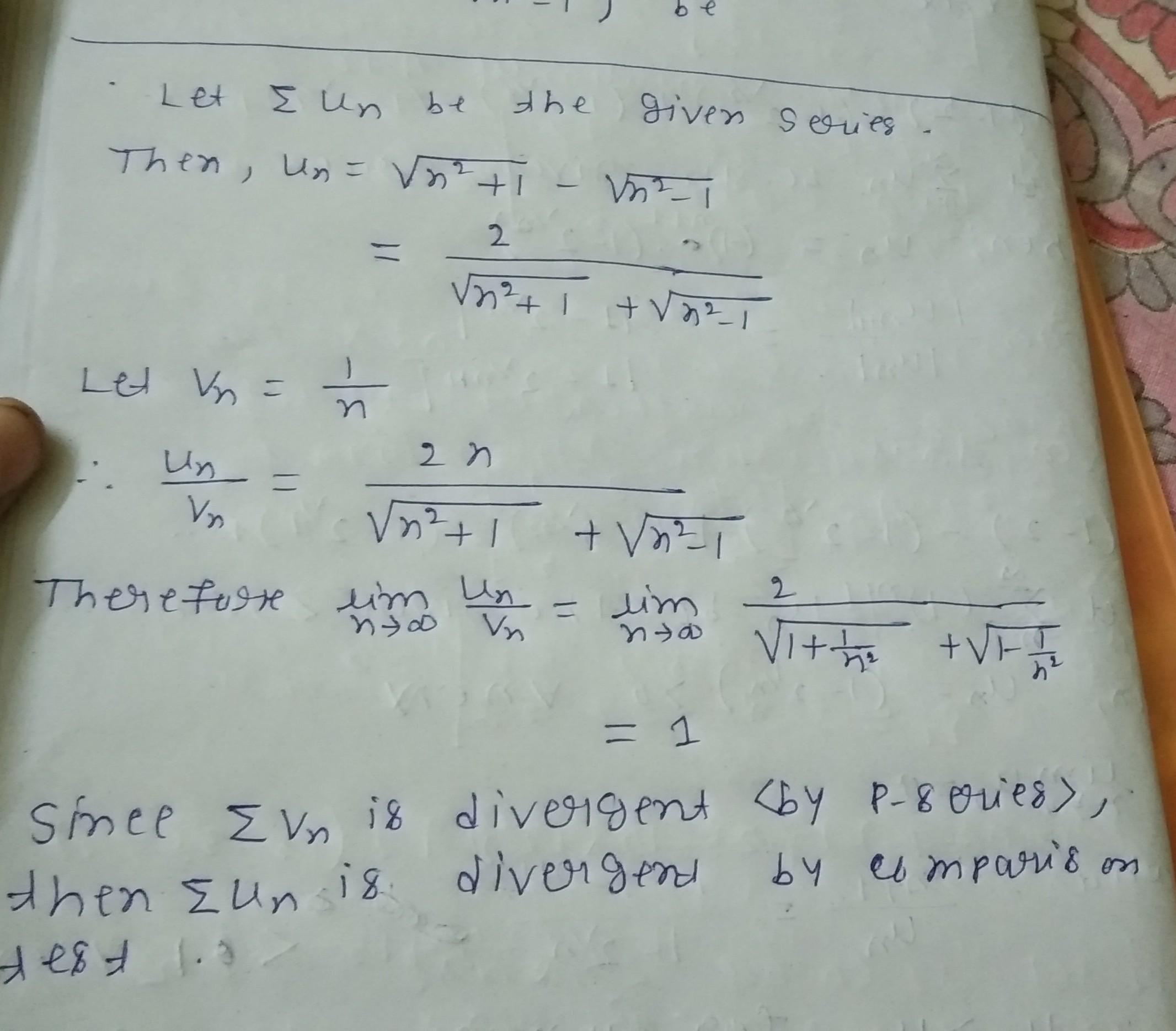

LCT is the more sophisticated cousin. Instead of worrying if one is strictly "smaller" than the other, you just look at their behavior at infinity. If the limit of the ratio of your series to a known series is a positive constant, they share the same fate. They’re "asymptotically" similar. This is incredibly powerful for dealing with messy polynomials. If you have $(n^2 + 5) / (n^4 - 3n)$, you just ignore the "noise" and compare it to $1/n^2$.

👉 See also: AP Physics C Electricity and Magnetism Equation Sheet: Everything You’ll Actually Need on Exam Day

Alternating Series and the Leibniz Rule

Things get weird when negative signs enter the chat. An alternating series like $1 - 1/2 + 1/3 - 1/4 \dots$ behaves differently than its all-positive counterpart. This specific example is the Alternating Harmonic Series, and unlike the regular Harmonic Series, it actually converges.

Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz gave us a simple three-step checklist for these:

- Are the terms alternating in sign?

- Are the absolute values of the terms decreasing?

- Does the limit of the terms go to zero?

If you hit all three, the series converges. This leads to the concept of Conditional Convergence. Some series only "behave" because the negative terms cancel out enough of the positive terms to keep the sum under control. If you took the absolute value of everything, they’d blow up to infinity. It’s a delicate balance.

Real World Stakes: Why We Actually Care

This isn't just academic torture. In the mid-20th century, engineers and physicists realized that representing functions as power series (Taylor series) was the only way to solve complex differential equations in fluid dynamics and quantum mechanics.

If an engineer uses a series to model the vibration of a bridge wing but doesn't check the convergence of series test properly, the model might suggest the bridge is stable when, in reality, the math "diverges" under certain conditions. That’s a catastrophic failure.

In digital signal processing, Fourier series allow us to break down complex sound waves into infinite sums of sines and cosines. Understanding where those sums converge determines the quality of the audio you're hearing right now. If the series didn't converge, the reconstruction of the sound would be literal noise.

Common Pitfalls and Nuances

A lot of people think that if a series converges, you can rearrange the terms however you want and get the same sum.

Nope.

That’s only true for Absolute Convergence. If a series is conditionally convergent, a famous result called the Riemann Rearrangement Theorem proves you can rearrange the terms to make the series add up to any number you want—including $\pi$, a billion, or negative forty-two. It’s one of the most counterintuitive facts in all of mathematics. It reminds us that "infinity" isn't just a big number; it's a different set of rules entirely.

Another mistake? Forgetting the "positive terms" requirement. Tests like the Integral Test or Comparison Test generally require $a_n > 0$. If your series has negative terms and doesn't alternate perfectly, you usually have to test for absolute convergence by taking the absolute value of everything first.

Actionable Steps for Mastering Series Tests

If you're staring at a problem set and feeling stuck, follow this flow to save time:

- Check the Limit First: Does the limit of the terms as $n$ goes to infinity equal zero? If not, stop. You're done. It diverges.

- Identify the "Shape": Is it a p-series ($1/n^p$)? Is it geometric ($r^n$)? These are your benchmarks.

- Look for Factorials: If you see $n!$ or $n^n$, go straight to the Ratio Test. It’s almost always the fastest way home.

- Simplify for Comparison: If the series is a bunch of polynomials added together, look at the highest powers. Use the Limit Comparison Test against the simplified version.

- Handle the Negatives: If it alternates, check the three Leibniz criteria. If it's messy with negatives, test the absolute value version first.

- The "Last Resort": If nothing else works, try the Integral Test, but only if the function looks easily integrable. Don't trap yourself in a 20-minute integration-by-parts loop if you don't have to.

Understanding these tests is about pattern recognition. The more you see, the faster you'll spot which tool fits the lock. It’s less about memorizing formulas and more about understanding the "speed" at which terms approach zero. If they vanish fast enough, you have a sum. If they linger too long, you have infinity.