You've probably watched a pot of water start to boil and noticed those weird, shimmying streaks rising from the bottom. Or maybe you've stood near a drafty window in the winter and felt the "ghost" of a cold breeze crawling across the floor. That's not magic. It’s physics. Specifically, it’s the definition of convection in action, and honestly, it’s the reason our planet isn't a frozen rock or a scorched desert.

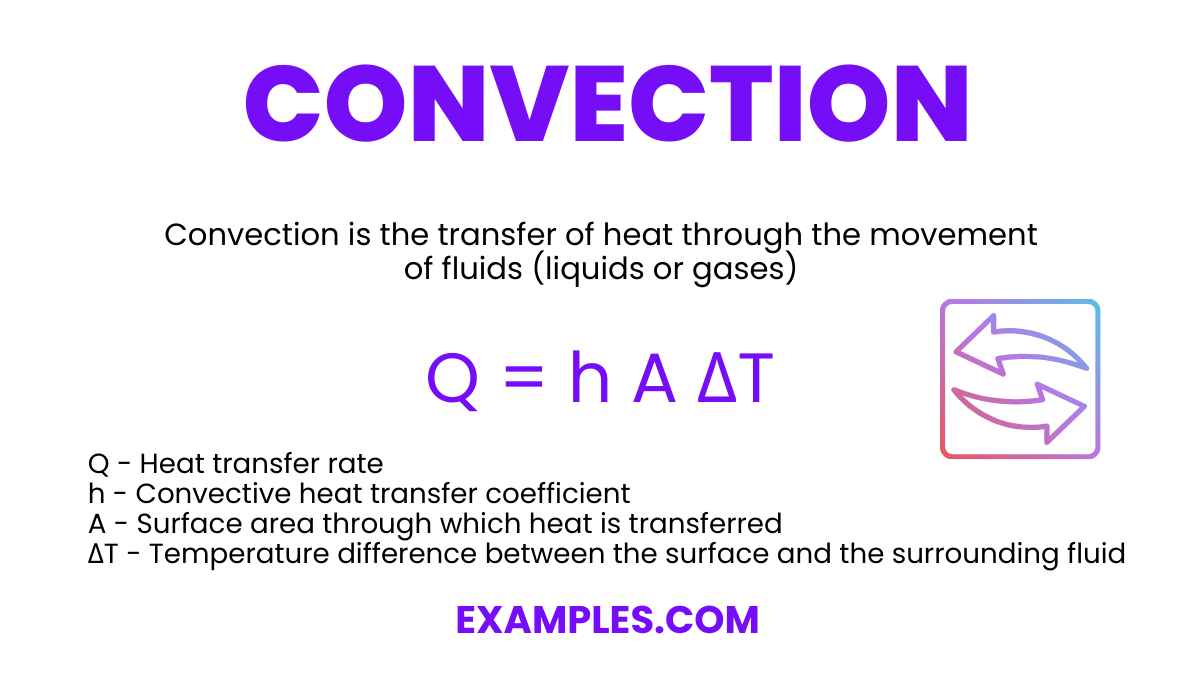

Convection is essentially the transfer of heat through the physical movement of a fluid. When scientists say "fluid," they don't just mean water or juice. In the world of thermodynamics, gases like air are fluids too. This is different from conduction—where heat travels through a solid object like a metal spoon—or radiation, which is how the sun toasts your skin from millions of miles away. Convection needs a medium that can flow.

How the definition of convection actually works in the real world

Basically, it comes down to density. Imagine a group of people standing in a room. If they all start dancing frantically, they’re going to need more space. Molecules do the same thing. When you heat up a liquid or a gas, the molecules start vibrating faster. They push away from each other. This makes that specific "patch" of fluid less dense than the cooler stuff around it.

Because it's lighter, it rises. As it moves away from the heat source, it eventually cools down, gets "heavy" (more dense) again, and sinks back to the bottom. This creates a loop. Scientists call this a convection cell. It’s a literal conveyor belt for thermal energy.

You see this in your kitchen every day. In a standard oven, the heating element at the bottom warms the air. That hot air rises to the top, cools slightly, and drops back down. However, "convection ovens" speed this up by using a fan to force the air around. It’s a more aggressive way to apply the definition of convection, ensuring your cookies don't have burnt bottoms and raw tops.

Forced vs. Natural: The two flavors of movement

Not all convection is created equal. There’s a big distinction between "natural" (or free) convection and "forced" convection.

Natural convection happens because of gravity and buoyancy. Think of a hot cup of coffee. The steam rising off it is natural convection. No one is pushing that air; it’s moving because the hot air is lighter than the room air. It’s elegant and slow.

Forced convection is more blue-collar. It’s when we use a pump, a fan, or even the wind to move the fluid. Your car’s cooling system is a prime example. The water pump forces coolant through the engine block to soak up heat, then shoves it into the radiator where a fan blows air over the coils to carry that heat away. If you relied on natural convection to cool a modern internal combustion engine, it would melt into a puddle of aluminum in minutes.

The massive scale of Earth’s internal engines

If we zoom out from the kitchen, the definition of convection becomes much more dramatic. It’s the engine of the Earth. Beneath our feet, the mantle—which is mostly solid but behaves like a very, very slow-moving liquid over millions of years—is constantly churning.

Hot rock near the core rises, moves horizontally under the crust, and then sinks. This is the primary driver of plate tectonics. When you hear about earthquakes in California or volcanoes in Iceland, you’re basically looking at the results of a giant convection cell deep underground.

📖 Related: That Weird Sound of a Dial Up Modem: Why We Actually Had to Listen to It

The atmosphere works the same way. The sun hits the equator more directly than the poles. This creates massive rising columns of warm air that drive global wind patterns and ocean currents. The Gulf Stream, which keeps Europe much warmer than it should be based on its latitude, is part of this huge, liquid heat-exchange program. Without these currents, the planet's climate would be unrecognizable.

Why heat transfer isn't always "perfect"

In a textbook, the definition of convection looks like a perfect circle. In reality, it’s messy. Turbulence happens. When a fluid moves too fast or hits an obstacle, it stops flowing in smooth "laminar" layers and starts tumbling. This actually increases the rate of heat transfer because it mixes the hot and cold parts more thoroughly.

Engineers spend their entire lives trying to calculate something called the Heat Transfer Coefficient ($h$). It’s a nightmare of a variable because it changes depending on the shape of the surface, the speed of the fluid, and even how rough the material is. If you’re designing a heat sink for a high-end gaming PC, you’re obsessing over how to maximize the surface area so that convection can whisk heat away from the processor before it throttles.

Common misconceptions about convection

People often get confused between convection and conduction. If you touch a hot stove, that’s conduction—direct contact. If you hold your hand five inches above the stove and feel the heat rising, that’s convection.

Another weird one? Space. In the microgravity of the International Space Station (ISS), natural convection doesn't really work. Why? Because there’s no "up" or "down" created by gravity. Without gravity to make the dense, cold air sink, a candle flame on the ISS looks like a weird, blue sphere. The hot gases just sit there around the wick. If they didn't have fans on the ISS to move the air around, astronauts could actually suffocate in a "bubble" of their own exhaled carbon dioxide.

Technical nuances: The Rayleigh and Nusselt numbers

If you really want to get into the weeds, physicists don't just say "it's moving." They use dimensionless numbers to describe what's happening.

The Nusselt number ($Nu$) compares the heat transfer by convection to the heat transfer by conduction within the fluid. A high Nusselt number means convection is doing the heavy lifting.

The Rayleigh number ($Ra$) is what determines when natural convection actually starts. If the temperature difference isn't high enough to overcome the fluid's "thickness" (viscosity), nothing moves. But once you hit that critical Rayleigh threshold, the fluid suddenly "breaks" into those rolling patterns you see in a boiling pot. It’s a tipping point between stillness and motion.

Real-world applications you might not think about

- Meteorology: Thunderstorms are just extreme convection. Warm, moist air shoots upward so fast it creates massive energy discharge.

- Architecture: Passive solar heating uses "Trombe walls" to circulate warm air through a house without using a single fan.

- Medical: Neonatal incubators use controlled convection to keep premature babies at a precise temperature without drying out their skin.

- Astrophysics: The Sun has a "convection zone" that makes up the outer 30% of its volume. It looks like a bubbling pot of plasma.

Actionable insights for everyday life

Understanding the definition of convection can actually save you money and keep you more comfortable.

- Check your ceiling fans: In the summer, you want the blades to push air down (counter-clockwise) to create a wind-chill effect (forced convection). In the winter, you should reverse the direction so it pulls air up. This gently pushes the warm air that's trapped at the ceiling back down the walls to the floor without creating a cold breeze.

- Don't block your radiators: If you have a radiator or a baseboard heater, it relies on "air chimneys." If you put a couch right in front of it, you’re killing the convection loop. The heat stays trapped behind the furniture instead of circulating through the room.

- Use the "Convection" setting on your oven wisely: It’s great for roasting meats and getting crispy skin because it strips away the "boundary layer" of moisture around the food. But for delicate cakes or soufflés? Turn it off. The moving air can actually blow the batter around or cause it to set too quickly.

- Seal your windows: "Drafts" are just unwanted convection currents. Even a tiny gap allows cold air to enter, sink to the floor, and push your expensive warm air toward the ceiling. Simple weather stripping breaks that cycle.

Convection is the reason the wind blows and the reason your soup gets hot. It’s the restless movement of a world trying to find a thermal balance that never quite arrives. Whether it’s the microscopic dance of water molecules in a kettle or the slow, grinding turn of the Earth's mantle, convection is the pulse of a living, breathing planet.