Ever looked at a map of the ocean floor and wondered why the steep drop-offs from the continents don't just hit a flat bottom immediately? It’s a bit of a trick of the eye. If you were to dive down past the shelf and the steep slope, you’d eventually hit a giant, gentle ramp of sediment. That’s the continental rise. It is basically the ocean’s version of a massive debris pile, but on a scale so huge it defines the very shape of our planet's basins.

Think of it as a transition zone. It’s where the "edge" of the continent finally settles into the deep, dark abyss. Without it, the seafloor would look like a jagged, unfinished construction site.

Defining the Continental Rise in Plain English

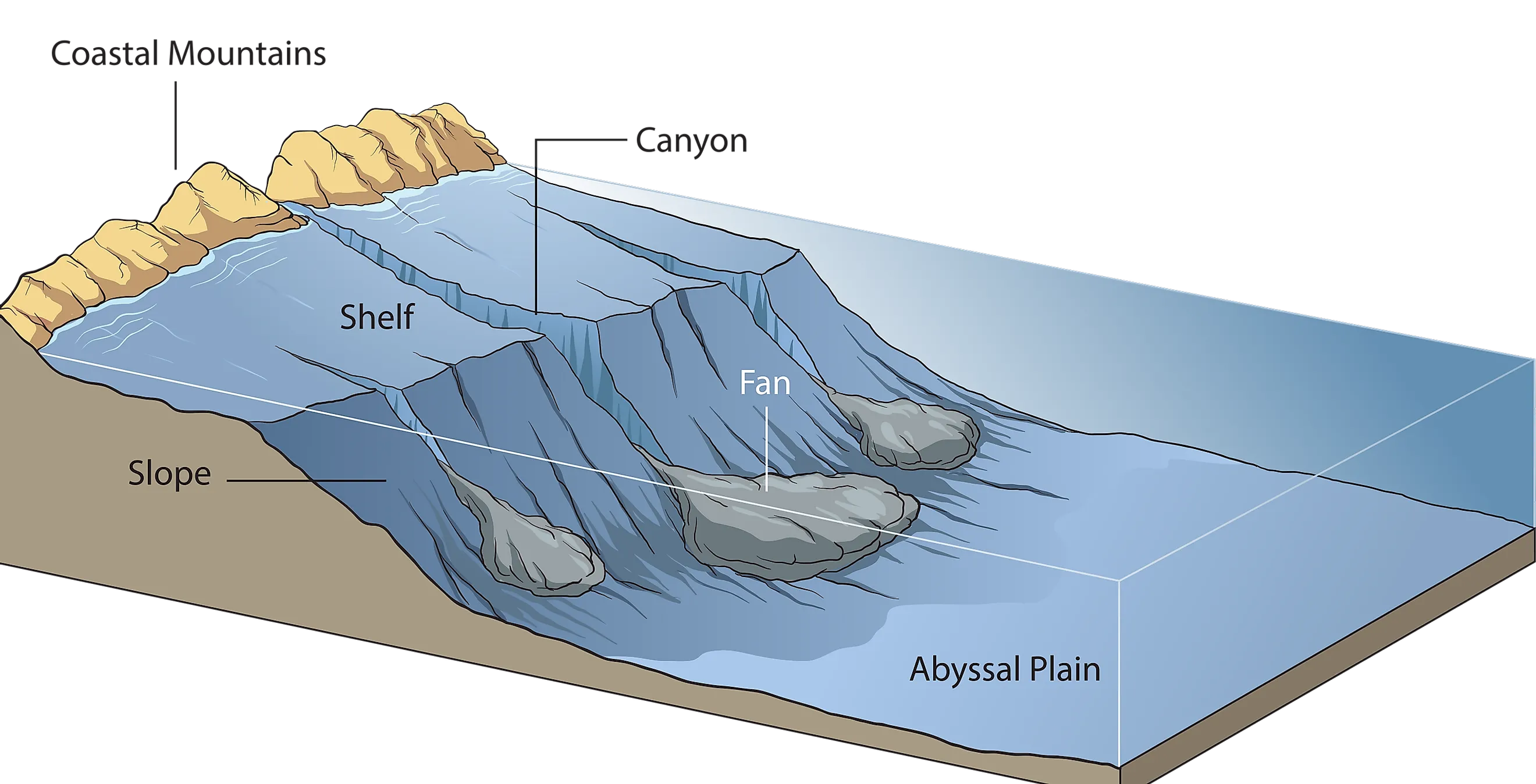

So, what is the actual definition for continental rise? In the simplest terms, it’s a wide, gentle incline that sits between the steep continental slope and the flat abyssal plain. If the continental slope is a cliff, the rise is the pile of scree and dirt at the bottom. But instead of just rocks, we are talking about thousands of meters of mud, sand, and silt that have been sliding off the land for millions of years.

Geologically, it represents the final boundary of the continental margin. You have the shelf (the shallow part where you swim), the slope (the big drop), and then the rise.

It’s not steep. Not at all. We are talking about a gradient of maybe 0.5 degrees to 1 degree. You wouldn't even notice you were on a hill if you were walking on it. But it stretches out for hundreds of miles.

How This Giant Ramp Actually Forms

The ocean is surprisingly messy. Over eons, rivers carry sediment into the sea. This stuff settles on the shelf, but it doesn't always stay there. Sometimes, an earthquake or just the sheer weight of the mud triggers what scientists call a turbidity current.

Imagine an underwater landslide. It’s a high-speed slurry of water and grit that screams down the continental slope. When it finally hits the bottom, it loses steam and spreads out. This process creates "deep-sea fans." They look exactly like the alluvial fans you see at the base of mountains in the desert, just underwater and much, much bigger.

The Role of Contour Currents

Gravity isn't the only thing at work here. You also have contour currents. These are deep-ocean currents that flow parallel to the continental margin. They act like a giant broom, sweeping sediment along the base of the slope and smoothing it out. This is why the rise isn't just a series of messy piles but a relatively smooth, continuous feature.

Geologists like Dr. Bruce Heezen, a pioneer in ocean floor mapping, were among the first to really highlight how these "contourites" shape the rise. It’s a dynamic environment, even if it looks like a desert of mud from a submersible window.

Where the Continental Rise Actually Exists (And Where It Doesn't)

Here is a weird fact: not every coastline has one. This is a huge point of confusion for students.

💡 You might also like: Hawaii Volcanoes National Park Entrance Fee: What Most People Get Wrong

If you are on the East Coast of the United States—a "passive margin"—the continental rise is massive. There is no tectonic plate boundary nearby to eat up the sediment. The mud just keeps piling up, building a thick wedge.

But go to the West Coast, or the coast of Chile. These are "active margins." Here, the oceanic plate is sliding under the continental plate (subduction). Instead of a gentle rise, you get a deep-sea trench. Any sediment that falls off the slope gets swallowed by the trench and dragged down into the Earth’s mantle. It’s a conveyor belt that prevents the rise from ever forming.

- Passive Margins: Large, well-developed continental rises (e.g., Atlantic Ocean).

- Active Margins: Little to no rise; usually replaced by a trench (e.g., Pacific Ocean "Ring of Fire").

Why This Mud Pile Actually Matters to You

You might think a bunch of underwater mud is boring. Honestly, it's not.

First, there is the oil and gas aspect. Because the continental rise is made of thick layers of organic-rich sediment buried over millions of years, it is a prime spot for hydrocarbon formation. Much of the world's untapped fossil fuel potential sits right under these deep-sea fans.

Then there’s the climate record. The layers of the rise are like the rings of a tree. By drilling into them, scientists can see how the Earth's climate has shifted. They find ancient pollen, shells of microscopic creatures, and dust from volcanic eruptions that happened 100,000 years ago. It’s a giant, wet history book.

Biodiversity in the Dark

It's also a surprisingly busy place for life. While it doesn't have the sunlight of a coral reef, the rise is a "benthic" wonderland. Sea cucumbers, brittle stars, and specialized deep-sea fish roam these plains, scavenging the "marine snow"—bits of dead stuff—that falls from above.

Misconceptions About the Deep Sea

People often confuse the rise with the abyssal plain. They are neighbors, but they aren't the same. The abyssal plain is the flattest place on Earth. It’s the true "bottom." The rise is the transition.

Another mistake? Thinking it's just sand. In reality, it's a complex mix of "hemipelagic" mud (clay and silt from the continents) and "pelagic" ooze (mostly tiny shells from dead plankton). It’s a weird, gooey cocktail.

How to Identify a Continental Rise in Data

If you’re looking at bathymetric data or a sonar profile, the definition for continental rise becomes visually obvious.

📖 Related: Warren Street Tube Station: Why This Gritty Transport Hub is Secretly Vital to London

- Look for the "shelf break," where the water suddenly gets deep.

- Follow the steep drop of the continental slope.

- Look for the point where the angle flattens out significantly but isn't quite horizontal yet. That "shoulder" or "toe" is your rise.

Actionable Takeaways for Geography and Oceanography Enthusiasts

If you are studying oceanography or just curious about how the Earth works, here is how you can practically apply this knowledge:

- Check the Tectonics: Next time you look at a map, check if the coastline is near a plate boundary. If it’s in the middle of a plate (like the Atlantic coasts), look for a wide continental rise. If it’s near a boundary (like the Pacific coasts), look for a trench instead.

- Explore Bathymetry Tools: Use tools like Google Earth (in "Ocean" mode) or the NOAA Bathymetric Data Viewer. Zoom into the Atlantic coast of Africa or North America. You can actually see the texture of the deep-sea fans spreading out from the base of the slope.

- Understand Resource Distribution: Recognize that deep-water drilling usually targets these specific sediment wedges because that’s where the pressure and organic material intersect to create energy resources.

- Follow Research Vessles: Organizations like the Schmidt Ocean Institute or NOAA Ocean Exploration often livestream ROV (Remotely Operated Vehicle) dives. Pay attention when they transit from the slope to the plain—you are witnessing the rise in real-time.

The continental rise is the unsung hero of the ocean floor. It’s the final bridge between the world we know and the vast, alien plains of the deep sea. Understanding it gives you a much clearer picture of how our planet recycles its land and stores its history under miles of water.