Look at a map of the world. No, really look at it. If you squint your eyes just a little bit, you’ll notice something kind of eerie. The "nose" of Brazil fits almost perfectly into the "armpit" of Africa. It’s like a giant, global jigsaw puzzle that someone just tossed onto the floor. For centuries, people saw this and just shrugged. They thought it was a coincidence or maybe the result of some biblical flood. But then came Alfred Wegener. He looked at that map and saw something else entirely. He saw a planet that used to be one giant piece.

The idea of continental drift is basically the suggestion that our continents aren’t fixed. They aren't anchored to the bottom of the ocean like giant stone pillars. Instead, they’re drifting. They’re moving, sliding, and crashing into each other at about the same speed your fingernails grow. It sounds totally normal to us now because we learned it in third grade, but back in 1912, telling a geologist that Africa was moving was like telling a modern doctor that ghosts cause the flu. They thought Wegener was out of his mind.

The Man Who Saw Too Much

Alfred Wegener wasn't even a geologist. He was a meteorologist. A weather guy. Maybe that’s why he was able to see the big picture without getting bogged down in the rigid "earth is solid" dogma of his time. He started noticing things that didn't make sense if the continents had always been where they are now. He found fossils of the Mesosaurus—a small freshwater reptile—in both South America and South Africa.

Think about that for a second. This little guy couldn't swim across the Atlantic Ocean. It’s physically impossible. He’s a freshwater animal. So, how did he get to both sides? Either he had a very tiny boat, or the two landmasses were touching when he was alive. Wegener went deeper. He found matching rock layers in the Appalachian Mountains of North America and the Scottish Highlands. He found evidence of ancient glaciers in the middle of the scorching Indian jungle.

The evidence was screaming at him.

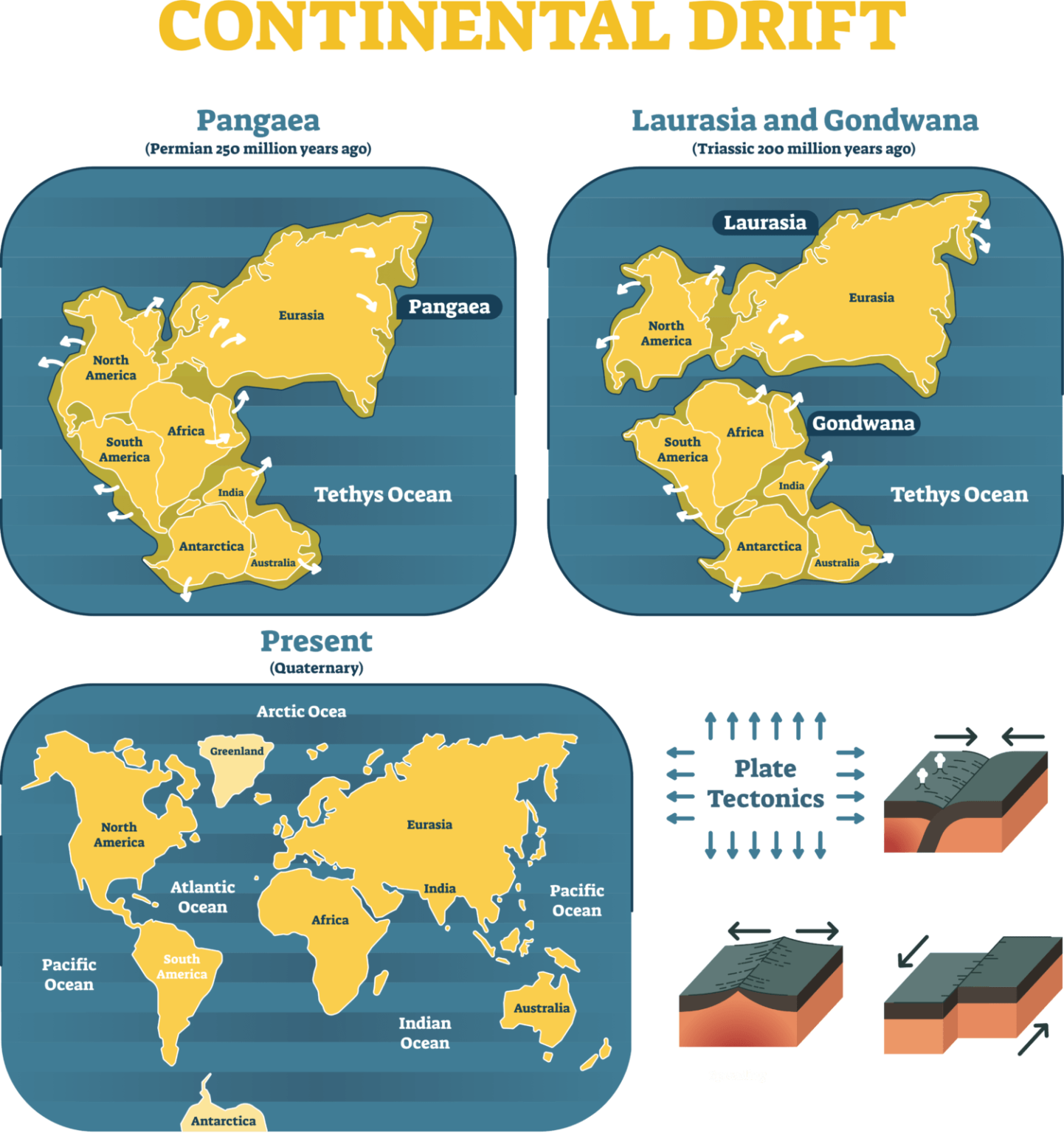

He called his supercontinent Pangaea. It’s Greek for "all lands." He imagined this massive, singular landmass surrounded by a giant ocean called Panthalassa. About 200 million years ago, this giant cracker started to crumble. It broke into two smaller pieces—Laurasia in the north and Gondwana in the south—and eventually, those pieces shattered into the continents we recognize today.

Why Everyone Thought He Was Crazy

Scientific progress isn't a straight line. It’s a messy, ego-driven brawl. When Wegener published The Origin of Continents and Oceans, the scientific community didn't just disagree; they were downright mean. A geologist named Rollin T. Chamberlin famously asked, "If we are to believe Wegener's hypothesis, we must forget everything which has been learned in the last 70 years and start all over again."

They had a point, though. Wegener had the "what" (the continents moved) but he didn't have the "how."

He suggested that the continents plowed through the ocean floor like icebreakers through the Arctic. He even thought the centrifugal force of the Earth's rotation or the tidal pull of the moon might be pushing them. This was objectively wrong. Physicists quickly did the math and showed that the moon's gravity isn't nearly strong enough to move a continent. If it were, the Earth would literally stop spinning. Because he couldn't explain the engine behind the movement, his peers threw the whole theory in the trash.

Wegener died in 1930 on an expedition in Greenland. He died frozen, still trying to prove his theory, never knowing that he would eventually be hailed as one of the greatest scientists in history.

The Smoking Gun at the Bottom of the Sea

The idea of continental drift didn't actually gain traction until the 1950s and 60s, long after Wegener was gone. And it wasn't fossils that saved him—it was submarines.

During World War II and the Cold War, the military spent a lot of time mapping the ocean floor. They expected it to be a flat, boring desert of mud. Instead, they found the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. It’s the longest mountain range on Earth, and it’s hidden entirely underwater.

Enter Marie Tharp and Bruce Heezen. Tharp was a cartographer who took the raw data from the sonar pings and turned it into a map. She noticed a massive rift valley running right down the center of the ridge. It looked like the Earth was being pulled apart. When she told Heezen it looked like continental drift, he dismissed it as "girl talk." It took him years to admit she was right.

Then came the paleomagnetism. This is where things get really wild. When lava cools, the iron minerals inside line up with the Earth's magnetic field, like tiny compass needles. But the Earth’s magnetic poles flip every few hundred thousand years. North becomes South; South becomes North.

Scientists found a "zebra stripe" pattern of magnetic reversals on the ocean floor. The stripes were perfectly symmetrical on both sides of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. This was the proof. The ocean floor was acting like a giant conveyor belt. New crust was being born at the ridge, pushing the old crust—and the continents attached to it—away. This process is called seafloor spreading.

Plate Tectonics: The Modern Version

We don't really call it "continental drift" anymore. We call it Plate Tectonics. It’s the upgraded, high-definition version of Wegener’s original idea.

Basically, the Earth’s outer shell (the lithosphere) is broken into about 15 to 20 huge slabs called tectonic plates. These plates sit on top of a hot, semi-liquid layer called the asthenosphere. Think of it like giant rafts of rock floating on a sea of hot taffy. The engine driving it all is convection. Heat from the Earth’s core rises, moves sideways as it cools, and then sinks back down. This creates a circular motion that drags the plates along for the ride.

There are three main ways these plates interact:

- Divergent Boundaries: They pull apart. This is happening in the Atlantic and the Great Rift Valley in Africa.

- Convergent Boundaries: They smash together. If two continental plates hit, they crumple up and make mountains, like the Himalayas. If an ocean plate hits a continental plate, the ocean plate slides underneath (subduction), creating volcanoes and deep trenches.

- Transform Boundaries: They slide past each other. This is the San Andreas Fault. They get stuck, pressure builds up, and then snap—you get an earthquake.

Why You Should Care Today

The idea of continental drift isn't just about ancient history. It’s happening right now.

✨ Don't miss: We Are Charlie Kirk: Why This Movement Reshaped Modern Political Activism

In about 250 million years, scientists predict we’ll have a new supercontinent: Pangaea Proxima. Africa is currently moving north and will eventually smash into Europe, erasing the Mediterranean Sea and turning the Alps into a massive mountain range that makes the Himalayas look like hills. Australia is heading toward Southeast Asia.

Understanding this movement is how we predict where earthquakes will hit and where volcanoes are likely to blow. It’s also how we find natural resources. If you find gold in a specific rock layer in Brazil, and you know Brazil used to be tucked into West Africa, you know exactly where to look for gold in Africa.

It’s also the reason for our climate. When Antarctica was connected to South America, it was actually quite green. Once it broke off and became surrounded by a cold ocean current, it froze solid. The very air you breathe and the temperature outside your window are products of these moving plates.

How to Visualize This Yourself

You don't need a PhD to see the evidence. You just need to know where to look.

- Check the Map: Look at the coastlines of the Atlantic. The fit isn't perfect because of erosion and rising sea levels, but the continental shelves (the underwater edges) fit like a glove.

- Google Earth Exploration: Fly over the Red Sea. You can see how the Arabian Peninsula is literally being ripped away from Africa. It’s a brand-new ocean in the making.

- Local Geology: If you live near a mountain range, look at the rocks. Often, you’ll find fossils of seashells at the top of a mountain. That's not because the ocean was that high—it’s because the plate tectonics took the ocean floor and shoved it into the sky.

The world feels solid under your feet. It feels permanent. But the idea of continental drift reminds us that we’re living on a very active, very restless machine. We're just along for the ride.

Actionable Insights for the Curious

- Visit a "Rift": If you're ever in Iceland, you can visit Thingvellir National Park. You can literally walk (or dive) between the North American and Eurasian tectonic plates. You can see the Earth pulling itself apart in real-time.

- Track Earthquakes: Download an app like MyRadar or visit the USGS earthquake map. You'll notice that 90% of earthquakes happen along the edges of these plates. It turns the world map into a connect-the-dots of tectonic activity.

- Study Paleogeography: Check out the work of Christopher Scotese. He has incredible animations showing the movement of continents over the last 500 million years and into the future. It changes your entire perspective on "home."

To wrap your head around the sheer scale of this, you have to stop thinking in human years and start thinking in "deep time." We are a blink of an eye in the history of a planet that is constantly reshaping itself. The continents are still moving. The map is still being drawn.