Look up. If you're away from the orange smear of city lights, you see a chaotic dusting of glitter. Most of us point at a bright spot and call it a star, or we find that one "big spoon" everyone knows. But honestly, the way we talk about constellation and star names is a mess of mistranslations, ancient PR campaigns, and literal optical illusions.

Space is big. Really big. Yet, the names we use to navigate it are surprisingly small, human, and often tied to who had the best ink and parchment 2,000 years ago.

The Map Isn't the Territory

A constellation isn't a "thing" in the way a mountain or a planet is a thing. It's a border. In 1922, the International Astronomical Union (IAU) basically sat down and carved the sky into 88 specific patches. Think of them like states or provinces. When we talk about constellation and star names, we’re usually mixing up the "asterism"—the recognizable shape—with the official celestial real estate.

Take the Big Dipper.

It isn't a constellation. It’s an asterism. It lives inside Ursa Major (the Great Bear). If you tell an astronomer you found the constellation of the Big Dipper, they might politely correct you, or just sigh. The distinction matters because many stars within a single constellation have zero physical relationship to each other. One might be 40 light-years away, while its "neighbor" in the sky is 1,000 light-years back. They just happen to line up from our very specific, tiny porch in the universe.

Where Star Names Actually Come From

If you look at a star chart, you’ll notice something weird. The constellations have Latin names (Orion, Cassiopeia, Scorpius), but the individual stars? They sound totally different.

Betelgeuse. Rigel. Aldebaran. Deneb.

Basically, we’re looking at a linguistic car crash between Rome and the Golden Age of Islam. During the Middle Ages, while Europe was busy forgetting its own name, scholars in the Middle East were meticulously cataloging the heavens. They translated Greek texts from Ptolemy’s Almagest and added their own observations.

📖 Related: Bates Nut Farm Woods Valley Road Valley Center CA: Why Everyone Still Goes After 100 Years

Most star names are just literal descriptions of where the star sits on the "body" of the constellation.

- Betelgeuse (Yad al-Jauzā') translates roughly to "the hand of the giant."

- Deneb simply means "tail." There are actually several "Denebs" in the sky, like Denebola in Leo (tail of the lion).

- Rigel comes from "Rijl," meaning "foot."

It’s not very poetic when you realize we’re just pointing at a sky-bear and saying "tail" or "foot" in Arabic, but it’s remarkably practical for navigation.

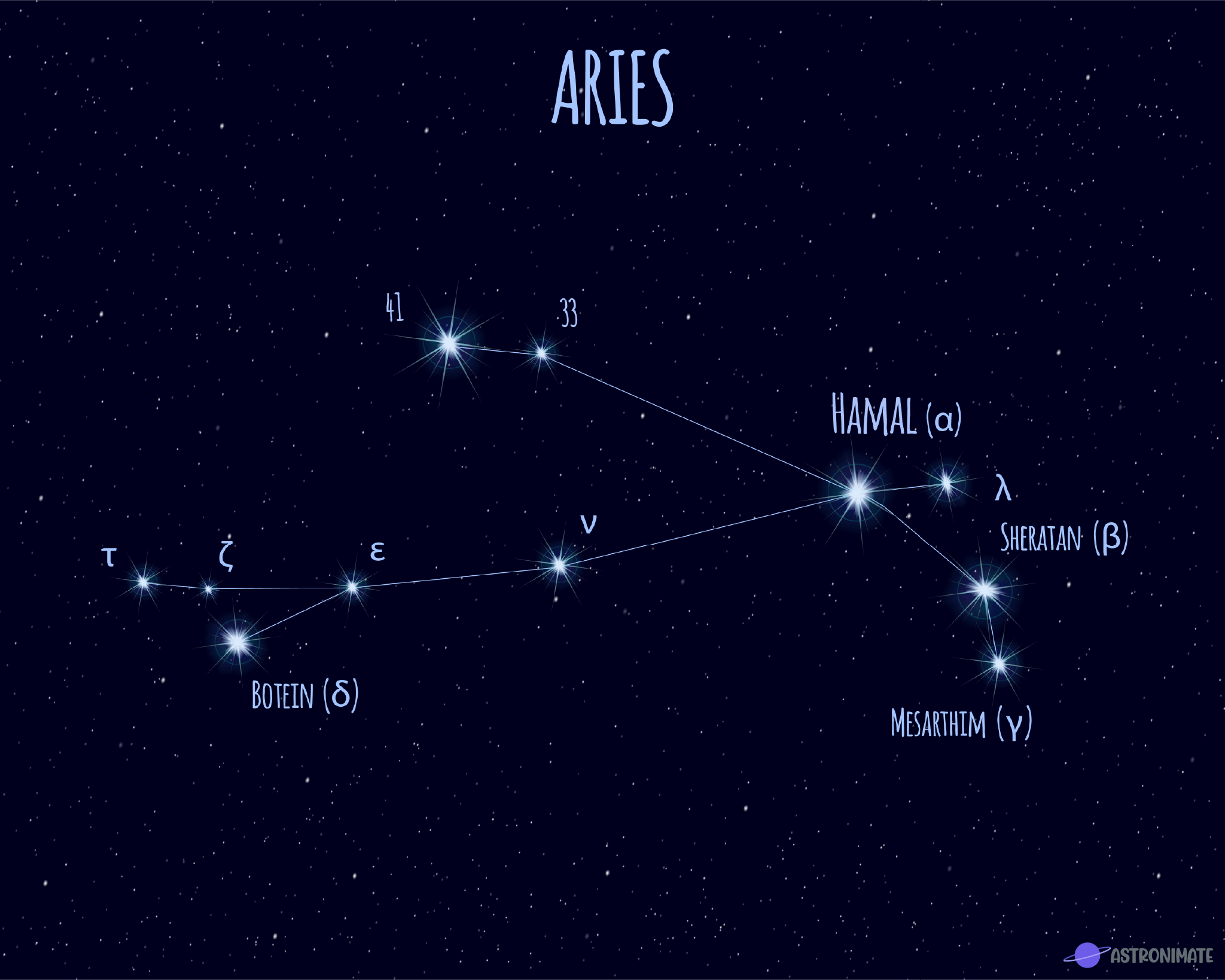

The Bayer Designation Mess

By the 1600s, we realized we were running out of cool names. German uranographer Johann Bayer decided to get organized. He started labeling stars using Greek letters based on their brightness within a constellation.

In theory, Alpha is the brightest, Beta is second, and so on.

It’s a great system until it isn't. Take Orion. Betelgeuse is Alpha Orionis, but Rigel (Beta Orionis) is actually brighter most of the time. Betelgeuse is a variable red supergiant; it dims and brightens like it's breathing. Sometimes it throws a tantrum and ejects a massive cloud of dust, making it look much dimmer to us on Earth. Bayer didn't have a telescope to see that coming.

Why You Can't "Buy" a Star Name

You've seen the ads. Pay $50, get a glossy certificate, and name a star after your girlfriend.

Don't.

👉 See also: Why T. Pepin’s Hospitality Centre Still Dominates the Tampa Event Scene

It's a scam. Or, more accurately, it’s an expensive piece of paper. The only organization that officially assigns constellation and star names is the IAU. They don’t sell names. If you buy a star name from a private company, the only place that name exists is in that company’s private ledger. NASA isn't using it. Professional observatories aren't using it. It’s a gift that exists in a vacuum.

If you want a real name in the sky, you usually have to discover a comet or an asteroid. Even then, there are strict rules. You can't name an asteroid after yourself—that's considered tacky in the scientific community. You have to name it after someone else, and even then, the Minor Planet Center has to give it the thumbs up.

The Cultural Bias of the 88

We use the 88 "official" constellations because that’s the tradition that won out globally, but it’s heavily Eurocentric. The Greeks and Romans saw hunters and queens.

Other cultures saw the same stars and told entirely different stories:

- In many Indigenous Australian traditions, the "Emu in the Sky" isn't made of stars at all. It’s made of the dark patches (the Great Rift) in the Milky Way.

- In ancient China, the sky was divided into Four Symbols and 28 Mansions. The groupings were much smaller and focused on imperial bureaucracy.

- The Polynesians used "star paths" for navigation, grouping stars that rose and set at the same declination to act as a compass.

When we fixate only on the Western constellation and star names, we lose the depth of how humans have used the sky for survival for 50,000 years.

The Physics of a Name: Why Color Matters

When you look at stars like Antares or Sirius, the name often hints at the physical reality.

Antares means "Anti-Ares" or "Rival of Mars." Why? Because it’s a deep, bloody red. It looks so much like the planet Mars that ancient observers often got them confused when Mars wandered nearby.

✨ Don't miss: Human DNA Found in Hot Dogs: What Really Happened and Why You Shouldn’t Panic

Sirius, the "Dog Star," comes from the Greek for "glowing" or "scorching." It’s the brightest star in our sky. It’s so bright that it doesn't just twinkle; it scintillates. It flashes through a rainbow of colors as its light is whipped around by Earth's atmosphere. If you see a low-hanging "UFO" changing colors rapidly, it’s almost certainly Sirius having a bad hair day in the lower atmosphere.

How to Actually Learn the Names Without a Degree

You don't need a PhD to get good at this. You just need a bit of spatial awareness and a refusal to use those glitchy AR phone apps that jitter every time you move your wrist.

- Start with the "Anchor" stars. Find Orion in winter or the Summer Triangle (Vega, Deneb, Altair) in summer. These are your landmarks.

- Star Hopping. This is the secret trick. Use the "arc" of the Big Dipper’s handle to "Arc to Arcturus." Then, "Speed on to Spica." Once you learn the physical relationship between these constellation and star names, the sky stops being a random scatter and starts being a map.

- Binoculars are better than telescopes for beginners. Telescopes have a tiny field of view. It's like looking at a wall through a straw. Binoculars let you see the context of the constellation.

- Watch the "Zodiacal Light." If you're in a dark spot, you can see the plane where the planets live. If a "star" isn't twinkling, it’s a planet. Planets don't get cool names like "Zubenelgenubi"—they just get the names of Roman gods.

The Future of Naming

We are discovering thousands of exoplanets—planets orbiting other stars. For a long time, these were just given boring codes like HD 209458 b.

But recently, the IAU has started the "NameExoWorlds" project. They’re letting the public vote on names for these systems. Now we have stars named Cervantes and planets named Quijote. It’s a bit more "human" than a string of numbers.

As our telescopes get better, we’re realizing that many "single" stars are actually triplets or quadruplets. Mizar and Alcor in the Big Dipper’s handle are a classic example. To the naked eye, they are two stars. Under a telescope, Mizar is itself a double star. It turns out the universe is way more crowded than our ancient naming systems ever anticipated.

Actionable Next Steps for Stargazing

If you want to move beyond just staring at dots, here is how you actually master the sky:

- Download Stellarium (Desktop version). It’s free and much more powerful than phone apps. You can rewind time to see how the sky looked when the Egyptians built the pyramids or how it will look in 10,000 years.

- Get a Planisphere. It’s a plastic wheel that shows you the sky for any date and time. It doesn't need batteries, and it won't ruin your night vision with a bright screen.

- Learn the "pointers." The two stars at the end of the Big Dipper’s bowl always point directly to Polaris, the North Star. Once you find North, everything else falls into place.

- Visit a "Dark Sky Park." Use the DarkSiteFinder map. Seeing the Milky Way with your own eyes changes how you feel about these names. They stop being words in a book and start being markers of our place in the galaxy.

The sky is a living history book. Every time you say a star's name, you’re speaking a mix of Latin, Greek, and Arabic that has survived thousands of years of human chaos. That's worth a look up.