Color theory is weird. You’ve probably sat in a middle school art class staring at a color wheel, feeling like you totally understood how red and green belong together because of Christmas. But then you try to design a website or pick out a tie for a wedding and suddenly everything looks like a neon disaster. Honestly, the biggest hurdle is that we use terms like "complementary" and "contrasting" interchangeably in casual conversation. They aren't the same. Not even close.

When people talk about complementary colors vs contrasting colors, they’re usually looking for a way to make something "pop." But popping can mean "vibrant harmony" or it can mean "visual headache." Understanding the nuanced physics of how our eyes perceive light—and how our brains interpret those signals—is the difference between a professional-looking project and something that looks like a DIY accident.

The Science of Opposite Attracts

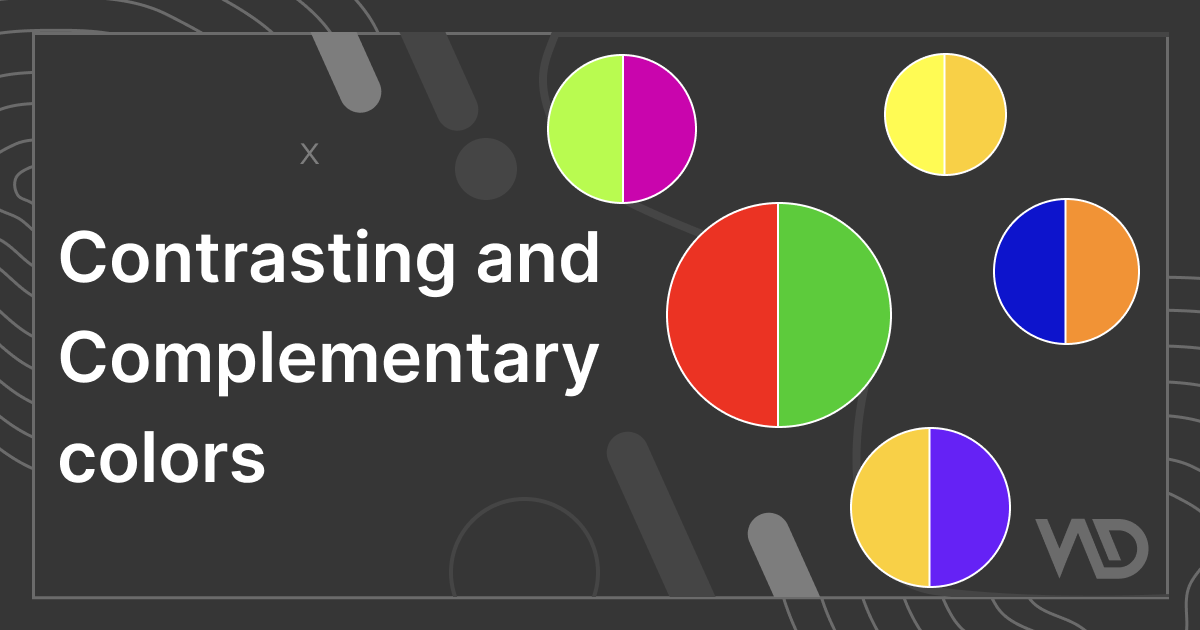

Complementary colors are pairs that sit directly across from each other on the color wheel. Think blue and orange, or yellow and purple. When you put them next to each other, they create the strongest possible contrast for those particular hues. It’s a high-energy relationship.

Why does this happen? It’s basically biological. Your eyes have photoreceptors called cones. When you stare at a lot of one color, say a bright red, those specific cones get tired. If you suddenly look at a white wall, you’ll see a ghostly green shape. That’s the "afterimage." Your brain is literally seeking the complement to find balance. This is why surgeons often wear green or teal scrubs; after staring at red blood for hours, the green helps neutralize the visual fatigue and keeps their vision sharp.

But here is the kicker: while complementary colors are technically a type of contrast, not all contrasting colors are complementary.

What Contrast Actually Is

Contrast is a broader bucket. It’s just the difference between two elements. You can have contrast in temperature (warm vs. cold), contrast in saturation (neon pink vs. dusty rose), or contrast in value (light vs. dark). Most of the time, when a room feels "off," it isn’t because the colors don't match. It’s because the values are too similar. If you take a photo of a room and turn it to grayscale, and everything is the same muddy shade of gray, you have zero contrast. It doesn't matter if you used "complementary" blue and orange; if they are the same level of brightness, they’ll just vibrate unpleasantly against each other.

Why Complementary Colors vs Contrasting Colors Matter in Design

Designers like Paula Scher or the folks at Pentagram don’t just pick colors that look "nice." They manage "simultaneous contrast." This is a phenomenon where the same color looks different depending on what is next to it.

💡 You might also like: Easy recipes dinner for two: Why you are probably overcomplicating date night

Imagine a small gray square.

If you put that gray square on a bright yellow background, the gray will actually start to look a bit purple. If you put it on a blue background, it might look slightly warm or orange. This is your brain trying to force a complementary relationship where one doesn't exist. Understanding complementary colors vs contrasting colors allows you to manipulate how the viewer perceives a single shade.

The Problem with High Intensity

Using pure, 100% saturated complementary colors is usually a mistake. If you put bright blue text on a bright orange background, the edges of the letters will appear to "jitter" or vibrate. This is called chromostereopsis. It happens because the different wavelengths of light focus on different parts of your retina. Your eye can’t decide where to focus, so it panics.

The fix?

Vary the values. Instead of navy blue and bright orange, try a very pale peach with a deep, dark navy. Now you have both complementary harmony and value contrast. It’s easier on the eyes and looks significantly more expensive.

Common Misconceptions About the Color Wheel

Most people use the RYB (Red, Yellow, Blue) model we learned as kids. It’s the "artist’s wheel." It’s great for mixing paint, but it’s technically "wrong" for digital screens or modern printing.

📖 Related: How is gum made? The sticky truth about what you are actually chewing

- RGB (Red, Green, Blue): This is for light. Your monitor uses it. Here, the complement of red is cyan, not green.

- CMYK (Cyan, Magenta, Yellow, Black): This is for ink. The complement of red is still cyan-ish.

- RYB: The old-school model.

If you’re wondering why your digital design looks muddy when you use "traditional" color rules, this is why. The physics of light (additive color) works differently than the physics of pigment (subtractive color). When you’re weighing complementary colors vs contrasting colors for a website, use an RGB-based wheel. If you’re painting your kitchen, stick to the RYB logic.

The 60-30-10 Rule

This is a classic interior design trick that solves the "too much contrast" problem. You don't want a 50/50 split between complementary colors. It's overwhelming.

- 60% Dominant Color: Usually a neutral or a muted tone.

- 30% Secondary Color: This provides the main contrast.

- 10% Accent Color: This is where you use that "pop" of a complementary color.

A living room might be 60% soft gray (dominant), 30% navy blue (secondary), and 10% burnt orange (complementary accent). This creates a sense of "visual weight" that feels intentional rather than chaotic.

Real World Examples of Color Conflict

Take a look at sports teams. The Chicago Bears use navy and orange. Those are complementary. The Los Angeles Lakers use purple and gold (yellow). Also complementary. These teams want to look high-energy and aggressive.

Now look at a brand like Tiffany & Co. They use "Tiffany Blue" and white. This is a "high-value contrast" but it is not a complementary relationship. It’s clean, calm, and expensive. If Tiffany's used a bright red-orange (the complement of their blue) as their secondary color, the brand would immediately lose its "luxury" feel and start looking like a clearance sale at a toy store.

How to Choose the Right Strategy

So, how do you decide between a complementary scheme and a more general contrasting one? It depends on the "mood" you're chasing.

👉 See also: Curtain Bangs on Fine Hair: Why Yours Probably Look Flat and How to Fix It

Choose Complementary Colors when:

- You want something to stand out immediately (like a "Buy Now" button).

- You are designing for sports, action, or high-energy environments.

- You want to create a sense of completion or "wholeness."

Choose General Contrast when:

- You want a sophisticated, "quiet" aesthetic.

- You need high readability for long-form text (black on white is the ultimate contrast).

- You’re working with a brand that needs to feel stable and professional.

The Role of Temperature

We can’t talk about complementary colors vs contrasting colors without mentioning temperature. Every color has a "bias." You can have a "cool" red (leaning toward violet) or a "warm" red (leaning toward orange).

If you’re trying to find a complement for a warm blue, you need a cool orange. If the temperatures don't align, the colors will "fight" even if they are technically opposites on the wheel. This is the "nuance" that AI tools usually miss. They see hex codes; humans see "feel."

Breaking the Rules

Sometimes, you want "discordant" colors. This is when you use colors that are close to each other on the wheel (analogous) but have slightly different values. It creates a sense of unease. Film directors like Wes Anderson or Quentin Tarantino do this constantly. They might use a palette that is almost entirely shades of mustard and brown, then throw in a single splash of jarring pink. That isn't a complementary choice—it’s a "conceptual contrast" designed to make the viewer feel a specific emotion.

Actionable Steps for Better Color Use

Stop guessing. If you want to master the balance of complementary colors vs contrasting colors, you need to change how you look at the world.

- Check the Grayscale: Take a photo of your design or your room. Turn the saturation to zero. If you can’t tell the difference between the objects, your contrast is too low, regardless of what colors you picked.

- Use the "Squint Test": Look at your project and squint until your vision blurs. Whatever shape stays visible the longest is your highest point of contrast. If that isn't the most important part of your project, you’ve misplaced your colors.

- Look at Nature: Evolution has already figured this out. Look at a bird's feathers or a flower. Nature rarely uses pure complements at high saturation. It uses "split-complements"—where you take a color (like green) and instead of using its direct opposite (red), you use the two colors next to the opposite (red-orange and red-violet). It’s softer and more sophisticated.

- Limit Your Palette: Most beginners use too many colors. Stick to three. Master the relationship between those three before trying to build a complex 5-color palette.

Color is a tool, not just a decoration. Whether you’re painting a canvas, styling an outfit, or building a brand, the goal is to guide the eye. Complementary colors are a shout; contrast is the language. Use the shout sparingly, or no one will hear what you're actually trying to say.