Ever looked at a modern map of the Southeast and wondered why South Carolina has that weird little "notch" taken out of its top left corner? Or why the line between the two Carolinas looks like a drunk person started drawing a straight line and then just gave up? Honestly, looking at a colony of South Carolina map from the 1700s is like looking at a rough draft of a document that nobody could agree on. It wasn't just about land; it was about power, rice, and a whole lot of confused surveyors hacking through swamps.

Back in 1663, King Charles II was feeling generous—mostly because he owed people money. He gave a massive chunk of North America to eight of his buddies, the Lords Proprietors. At the time, "Carolina" was one giant blob on the map. It stretched from the Atlantic all the way to the "South Seas" (the Pacific Ocean), which, let's be real, they hadn't even seen yet.

The Messy Divorce of 1712

For the first few decades, the colony was basically two separate worlds. You had the northern settlers around Albemarle Sound who were mostly small-time farmers, and then you had the southern crowd in Charles Town (Charleston) who were getting filthy rich off rice and indigo. They didn't really talk. They definitely didn't want to pay for each other's problems.

By 1712, the Lords Proprietors realized one governor couldn't handle the whole thing. The "divide" happened, but if you look at a colony of South Carolina map from that era, the boundary is... optimistic. They basically said, "Start 30 miles south of the Cape Fear River and go west." Easy, right?

Not exactly.

The surveyors sent out to mark this line had it rough. We're talking thick Carolina briers, massive swamps, and no GPS. They'd mark a tree with a hatchet, call it a day, and then the tree would die or get chopped down ten years later. This led to decades of "hey, that's my cow" and "no, this is my tax revenue" arguments between the two colonies.

📖 Related: Food in Kerala India: What Most People Get Wrong About God's Own Kitchen

The Map That Won the Revolution

If you're a map nerd, there’s one name you have to know: Henry Mouzon. In 1775, his map, An Accurate Map of North and South Carolina With Their Indian Frontiers, became the gold standard.

Here’s a cool bit of trivia: George Washington actually carried a copy of the Mouzon map in his saddlebag. So did the British General Henry Clinton and the French General Rochambeau. They were all using the exact same piece of paper to try and kill each other.

What made Mouzon’s map so special?

- It was the first time someone actually bothered to map the interior with real detail.

- It showed the "Indian Paths" and "Trading Paths" that were the highways of the 18th century.

- It marked specific plantations, which was basically the 1700s version of Google Street View.

But even Mouzon didn't get it all right. Some historians now think a guy named Louis Stanislas d'Arcy Delarochette did a lot of the heavy lifting, and Mouzon just got the credit because his name was on the engraving. Classic.

The Mystery of the Catawba Notch

Have you ever noticed that sharp "V" or "notch" in the border near Charlotte? That’s not a mistake. That’s the Catawba Indian Reservation.

👉 See also: Taking the Ferry to Williamsburg Brooklyn: What Most People Get Wrong

Back in 1763, the Treaty of Augusta set aside 15 feet—wait, no, 15 miles—square for the Catawba Nation. When the surveyors finally got around to drawing the state line in 1772, they had to swerve around the reservation. South Carolina wanted the Catawba land to stay within its borders, so the line took a sudden jagged turn. Even today, if you're driving on I-77, you're crossing a boundary defined by a 250-year-old treaty.

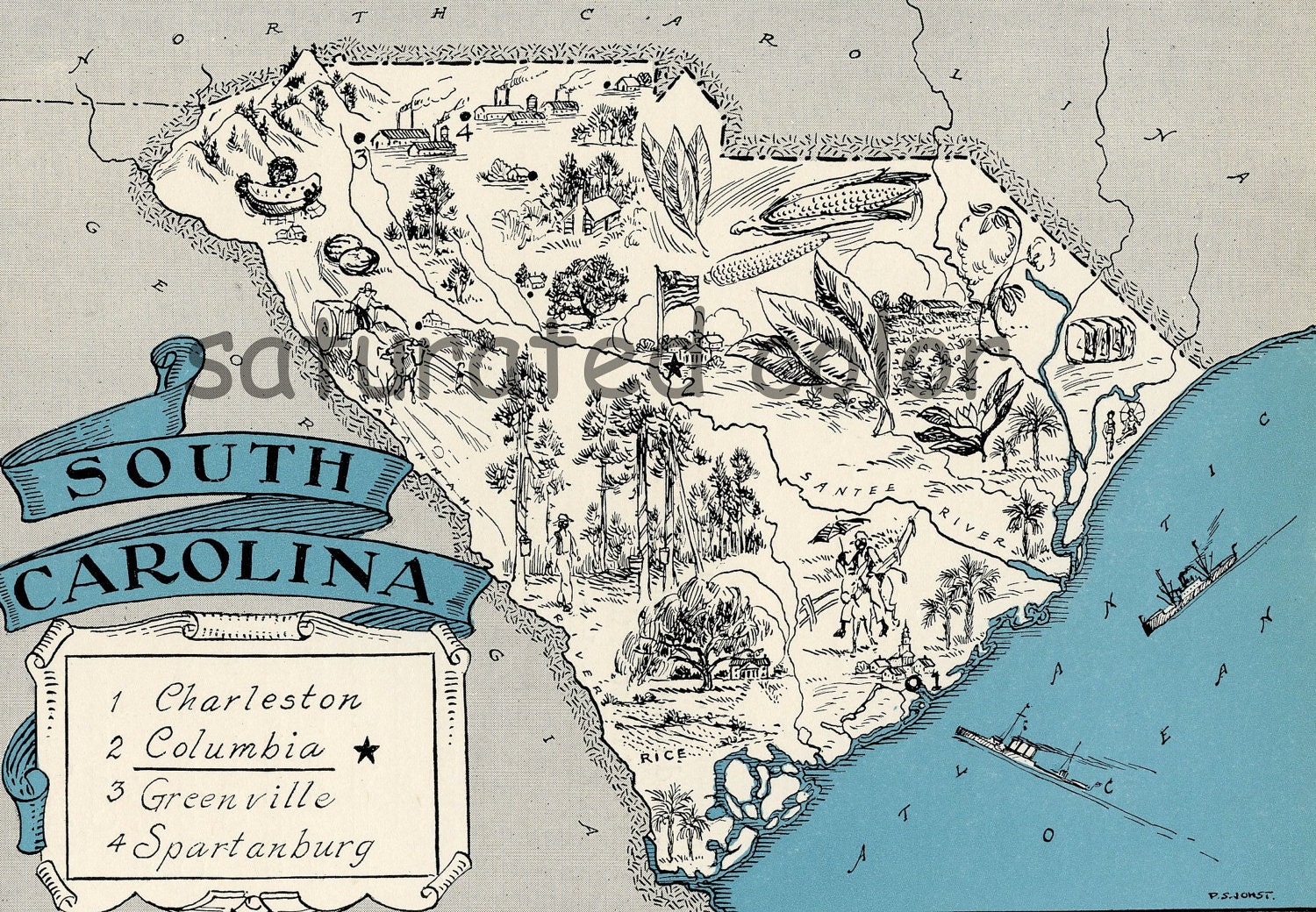

What a Colony of South Carolina Map Tells Us About Wealth

The maps don't just show rivers and roads; they show where the money was. If you look at James Cook’s 1773 map, the coastal "Lowcountry" is packed with detail. You can see the tiny squares representing rice fields.

Rice was "Carolina Gold." It made Charleston the wealthiest city in the colonies for a time. But that wealth was built on a brutal system. The maps show "Parishes" like St. Stephen's or St. James Goose Creek. These weren't just church boundaries; they were the political and economic units of the slave-holding elite.

The "Upcountry"—the area toward the mountains—looks almost empty on early maps. To the guys in Charleston, that was just "the backcountry." It was a place for "bold" (read: poor) Scots-Irish settlers to act as a buffer between the wealthy coast and the Cherokee Nation.

The Shifting Frontier

Speaking of the Cherokee, the western edge of any colony of South Carolina map was always "suggestive."

✨ Don't miss: Lava Beds National Monument: What Most People Get Wrong About California's Volcanic Underworld

- 1730s: The line stops at the "fall line" where rivers get rocky.

- 1760s: The boundary moves toward the Blue Ridge Mountains after the Cherokee War.

- 1777: Following the Treaty of Dewitt's Corner, the map expands again as the Cherokee were forced to cede almost all their land in what is now Anderson, Oconee, and Pickens counties.

Why Should You Care?

You’d think we’d have this figured out by now. Nope.

Believe it or not, North and South Carolina didn't "officially" finish settling their border until 2017. Seriously. They had to use GPS and old colonial records to figure out where the line actually was because some gas stations and houses were technically in the wrong state. People woke up one day and found out their kids were supposed to be going to school in a different state because of a 1735 survey error.

Takeaways for your next history rabbit hole:

- Check the Cartouche: The decorative art in the corner of old maps often shows what the colony valued—usually slaves, rice plants, or deer skins.

- Follow the Rivers: In the 1700s, a river wasn't just water; it was the only way to move goods. If a map is detailed around a river, that's where the power was.

- Look for the "Old Indian Paths": These often became the foundations for modern US highways.

If you want to see these for yourself, the South Carolina Department of Archives and History has a digital collection that'll keep you busy for hours. You can literally zoom in on individual farmsteads from 1773 and see who lived there. It’s the closest thing we have to a time machine.

To get the most out of your research, try comparing a 1775 Mouzon map side-by-side with a modern satellite view of the Santee River. You’ll be surprised how much of the original "skeleton" of the colony is still visible in the landscape today. You can also visit the South Caroliniana Library in Columbia to see some of these original engravings in person—just don't expect to find the "South Seas" on the other side of the Blue Ridge.