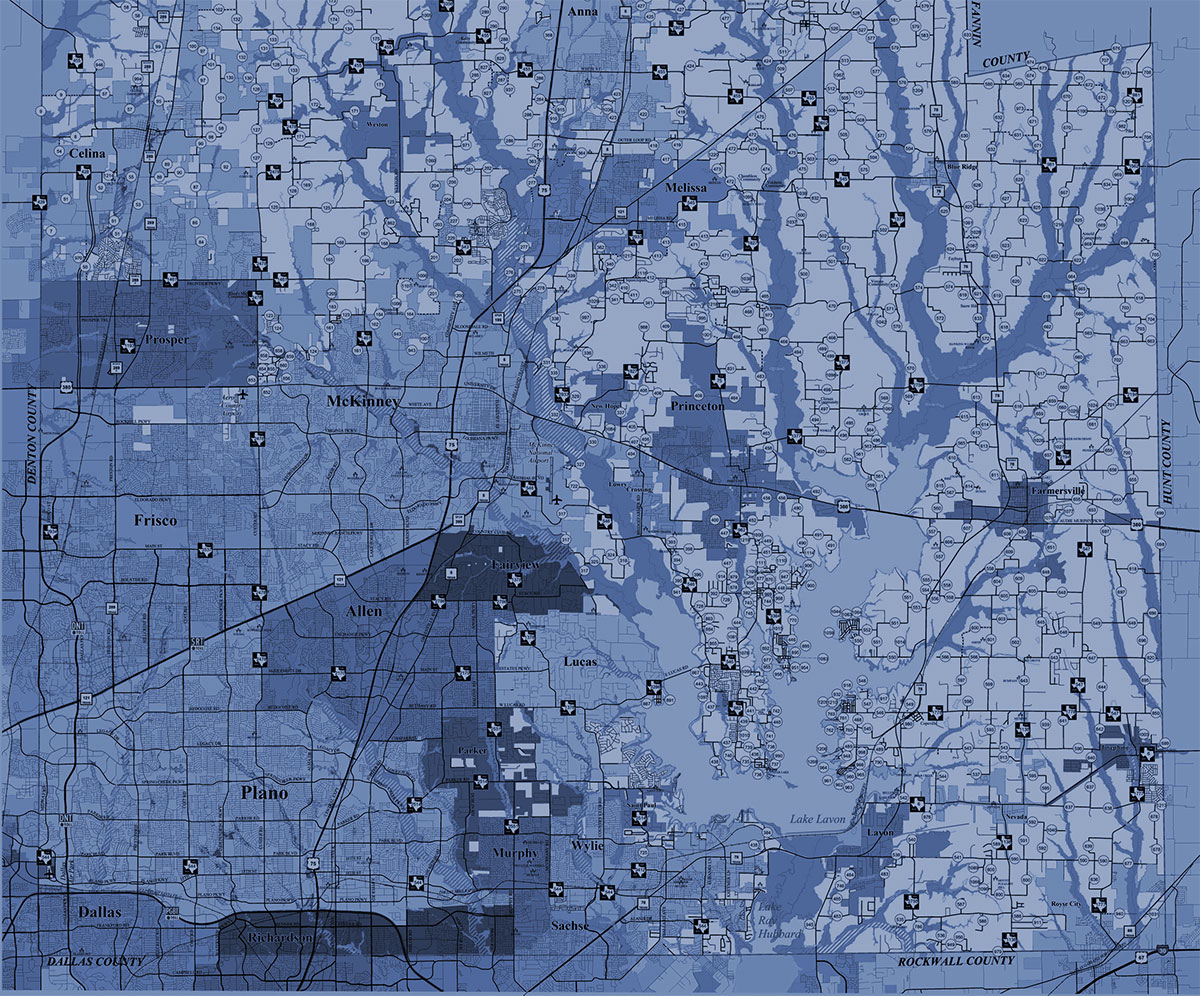

You're standing in your kitchen in Plano or maybe a coffee shop in McKinney, and you suddenly need to know who actually owns that strip of land behind your fence. Or maybe you're a first-time homebuyer trying to make sense of a massive PDF full of "Grantors" and "Grantees." Most people think property records are some dark art locked in a basement. Honestly? They're remarkably public, but they are also surprisingly easy to mess up if you don't know the "Collin County way" of doing things.

Buying a house is probably the biggest check you'll ever write. If you’re digging into collin county deed records, you aren’t just looking for a name; you’re looking for peace of mind. You’re making sure no one else has a "surprise" claim to your living room.

The Online Portal: It's Not Google

The biggest mistake people make is treating the Collin County Clerk’s search like a Google search. If you just type in "123 Main St," you might get nothing. Why? Because the Clerk’s office primarily indexes by name or instrument number, not physical address.

If you've only got an address, you have to take a detour. You’ve gotta head over to the Collin Central Appraisal District (CCAD) website first. You look up the address there to find the owner's name or the legal description (lot and block). Once you have that name, then you go back to the Clerk's land records portal.

✨ Don't miss: Shell Dividend: Why the World's Most Famous Payout Isn't What It Used to Be

It’s a two-step dance. Most people quit at step one and assume the records are missing. They aren't. You're just using the wrong key for the door.

Decoding the Numbers

Ever looked at a Collin County instrument number? If the document was recorded between 2006 and early 2022, it’s a 17-digit monster. It starts with the date: Year, Month, Day. For example, 20100505000078890 means it was filed on May 5, 2010.

But things changed recently. As of May 2, 2022, they switched to a 13-digit format. Now it’s just the year followed by a sequence, like 2022000568323. If you’re trying to track a chain of title across these two eras, the sudden change in digit count can be super confusing.

The Hidden Trap: Liens and Encumbrances

A deed tells you who owned it, but the "Official Public Records" (OPR) tell you who else has a slice of the pie. In Collin County, you aren't just looking for deeds. You're looking for:

- Deeds of Trust: This is basically your mortgage.

- Mechanic’s Liens: Did the previous owner stiff a pool contractor in Frisco? That lien is probably attached to the property records.

- Abstracts of Judgment: If someone lost a lawsuit, their debt might be sitting on that land.

I’ve seen people buy property at auction thinking they got a steal, only to realize there’s a $40,000 IRS lien that stayed with the land. The deed was "clear," but the record wasn't.

👉 See also: ENB Stock Price TSX: Why This High-Yield Giant is Kinda Weird Right Now

Filing Your Own Documents

If you’re actually filing something—maybe you’re transferring property to a family member or a trust—Collin County is strict. Really strict.

First, there's the Notice of Confidentiality Rights. If your document doesn't have that specific paragraph at the top in 12-point bold or all-caps, the clerk can (and likely will) reject it. It’s a Texas law thing, but Collin County enforces it to the letter.

Then there’s the margin. You need a 4-inch margin at the bottom of the last page for the filing stamp. If you cram your signatures all the way to the bottom, the clerk has to add a "blank" page just for the stamp. And guess what? They’ll charge you an extra $4 for that page.

Fees and Cold Hard Cash

Speaking of money, recording isn't free. For most land documents, you’re looking at $26 for the first page and $4 for every page after that.

If you’re heading to the office at 2300 Bloomdale Road in McKinney, bring your card or a check. They take Visa, Mastercard, and even Amex now, but they’ll hit you with a 2.34% "convenience fee." Honestly, it’s better than carrying a mountain of cash, but it adds up if you’re a developer filing fifty plats.

What About the Old Stuff?

Collin County was established in 1846. If you’re researching a historic home or a family farm, the online portal only goes back so far. For the really old stuff—we’re talking 19th-century handwritten ledgers—you might find yourself looking at microfilm at the University of Texas at Arlington or digging through the "Genealogy Corner" in the Clerk's archives.

🔗 Read more: William Lauder: Why the Estee Lauder Architect is Stepping Back Now

There’s something kinda cool about seeing a deed signed in 1880, but it’s a slow process. Those records aren't just data points; they're the history of North Texas.

Actionable Next Steps for Your Search

If you need to verify a property right now, don't just wing it. Follow this sequence:

- Start at the CCAD website. Search by address and copy the "Owner Name" and the "Legal Description" (e.g., "Stonebridge Ranch Estates Ph 4, Lot 12").

- Go to the Collin County Clerk’s Land Records Search. Use the "Name" search first. If that’s too cluttered (searching for "Smith" is a nightmare), try the "Legal" search using that description you found.

- Check for "Release of Lien." If you see a Deed of Trust from 2015, make sure there’s a corresponding Release filed later. If not, that mortgage might still be technically "active" in the eyes of the law.

- Download the Unofficial Copy. You can view the documents for free online to see if they’re what you need. If you need a "Certified Copy" for court or a bank, you’ll have to pay $1 per page plus a $5 certification fee.

- Watch the Margins. If you are drafting a deed yourself, leave that 4-inch space at the bottom. It saves you money and a headache at the counter.

Navigating collin county deed records is basically just a game of knowing which website to use first. Once you get the hang of the name-based indexing, you'll realize the information is all there, waiting for you to find it. Just make sure you're looking at the most recent filings, as the transition to the new 13-digit numbering system in 2022 means some older search methods might feel a little clunky.