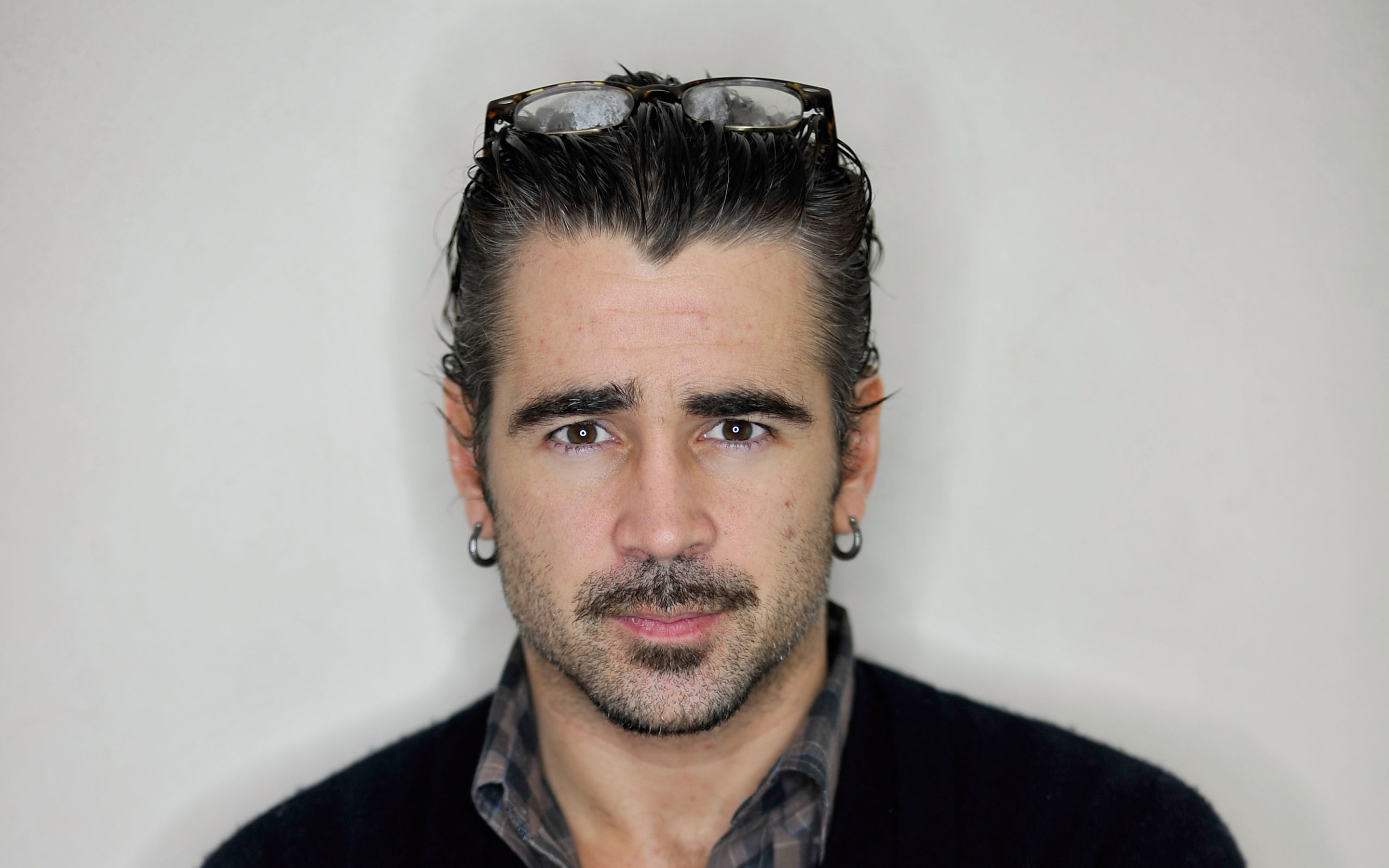

If you look at Colin Farrell’s filmography, you see two very different guys. One is the early 2000s tabloid fix, the "bad boy" of Hollywood who lived in leather jackets and blockbusters like S.W.A.T. or Daredevil. Then there’s the Farrell we have now—the one who does The Banshees of Inisherin and isn't afraid to look small, or weird, or heartbroken.

A lot of people think that shift happened recently. It didn't.

The real turning point was 2005. It was the year Colin Farrell and The New World happened, a movie that basically stripped him of every movie-star trick he had in his bag. Directed by the legendary (and notoriously difficult) Terrence Malick, this wasn't just another period piece. It was a total dismantling of Farrell’s public persona. Honestly, if you want to understand why he’s one of the best actors alive today, you have to look at what happened in the mud of Virginia twenty years ago.

The Chaos of Capturing John Smith

When Farrell signed on to play Captain John Smith, he probably expected a script. Most actors do. But Malick doesn't really work with scripts in the traditional sense. He works with "moments" and "moods."

The production was famously grueling. They filmed in Virginia, only about seven miles from where the actual Jamestown settlement was founded in 1607. Malick is a perfectionist of the weirdest kind. He didn’t want artificial lights. He didn’t want cranes. He wanted the actors to exist in the environment until they stopped "acting" and started just being.

Farrell has since described the experience as a "beautiful contradiction." On one hand, Malick was incredibly prepared—his vision was deep and specific. On the other hand, if a bird flew by and looked more interesting than the scene they were shooting, the camera would just follow the bird.

🔗 Read more: Jack Blocker American Idol Journey: What Most People Get Wrong

For a guy like Farrell, who was used to the rigid structure of big-budget action movies, this was a shock. He spent months literally covered in dirt, dealing with the humidity of a Virginia summer and the freezing cold of the winter. In some behind-the-scenes footage, you can see the cast looking genuinely exhausted. They were dealing with intestinal viruses, dehydration, and the sheer mental fatigue of never knowing if the scene they were filming would even make it into the movie.

Why the Performance Was Different

In Colin Farrell and The New World, his performance is almost entirely silent.

Think about that for a second. Farrell is a guy known for his fast-talking, Irish charm. In this movie, he’s a man in a cage. Literally. When we first meet John Smith, he’s a prisoner. He’s a roguish soldier who has seen too much war and has zero hope left.

Malick used voiceover to let us into Smith’s head, but on screen, Farrell had to communicate everything through his eyes and his physicality. It’s a "mute glaring," as some critics called it at the time, but it’s more than that. It’s a stripping away of ego.

There’s a specific scene where Smith first encounters the Powhatan people. Malick actually kept Farrell and Q'orianka Kilcher (who played Pocahontas) apart until the cameras were rolling for their first meeting. He wanted that "first contact" to feel authentic. You can see it in Farrell’s face—there’s a genuine sense of wonder and confusion that you just can't fake with three weeks of rehearsal.

💡 You might also like: Why American Beauty by the Grateful Dead is Still the Gold Standard of Americana

The Problem With Historical Accuracy

Let’s be real: The New World isn't a history textbook.

If you're looking for an accurate account of the Jamestown colony, you’re going to be annoyed. Historians have pointed out plenty of issues:

- The romance between Smith and Pocahontas is largely a myth created by Smith himself years later.

- Pocahontas was around 10 or 12 years old in 1607; Kilcher was 14 during filming, but the movie frames it as a grand, poetic romance.

- The scale of the Powhatan Confederacy is way too small in the film—there were thousands of people, not just a few dozen in a village.

But Malick wasn't trying to win a history award. He was making a "tone poem" about the loss of innocence. He wanted to show the "American Dream" at the exact moment it started to go wrong.

The Legacy of the "Malick Treatment"

At the time, the movie was a bit of a flop. It divided critics. Some people found it boring and "too much of a good thing." Others, like those at The Guardian, called it a misunderstood masterpiece.

For Farrell, the legacy was personal. He’s talked about how it taught him to be present. In an industry where everyone is obsessed with the "next shot" or the "next line," Malick forced him to just look at the wind in the grass or the way the light hit the river.

📖 Related: Why October London Make Me Wanna Is the Soul Revival We Actually Needed

You can see the influence of Colin Farrell and The New World in everything he’s done since. He stopped trying to be the "next Brad Pitt" and started being a character actor who happens to have a leading man’s face. He learned that silence is often louder than a five-minute monologue.

Actionable Takeaways for Film Fans

If you haven't seen the movie, or if you haven't seen it since 2005, here is how to actually approach it:

- Watch the Extended Cut: There are three versions of this movie. The 172-minute Criterion Collection "Extended Cut" is the one you want. It breathes better.

- Focus on the Sound: The score by James Horner is great, but the natural soundscape—the birds, the water, the wind—is actually the lead character.

- Don't Look for a Plot: This isn't an adventure movie. It’s a sensory experience. If you try to follow it like a standard 3-act film, you’ll get frustrated. Just let it happen to you.

The movie ends with a sense of "paradise lost," and in a way, it was the end of a certain era of Farrell’s career too. He left the "Old World" of Hollywood blockbusters behind and found something much more interesting in the "New World" of independent, visionary cinema.

If you want to see an actor actually transform—not with prosthetics or accents, but by just letting the environment change him—go back and watch this one. It’s a fever dream that’s finally getting the respect it deserved twenty years ago.

Next time you see a movie with a "wandering camera" or natural lighting, remember that this was the blueprint. It was the moment Farrell realized that sometimes, the best way to act is to just stop acting and start breathing.