If you’ve ever tried to weld thin aluminum and ended up with a gaping hole instead of a seam, you know the frustration. It’s a mess. Standard MIG welding—or Gas Metal Arc Welding (GMAW) if we’re being formal—is often just too hot. It’s like trying to use a blowtorch to light a candle; usually, you just melt the candle. That’s essentially why cold metal transfer exists. Developed by the Austrian company Fronius back in the early 2000s, it’s a process that sounds like an oxymoron. How can welding be cold? Well, it’s not literally freezing, but in the world of high-heat arcs, it’s about as chilled out as it gets.

Most people think welding is just "spark plus metal equals bond." Honestly, it’s way more fickle.

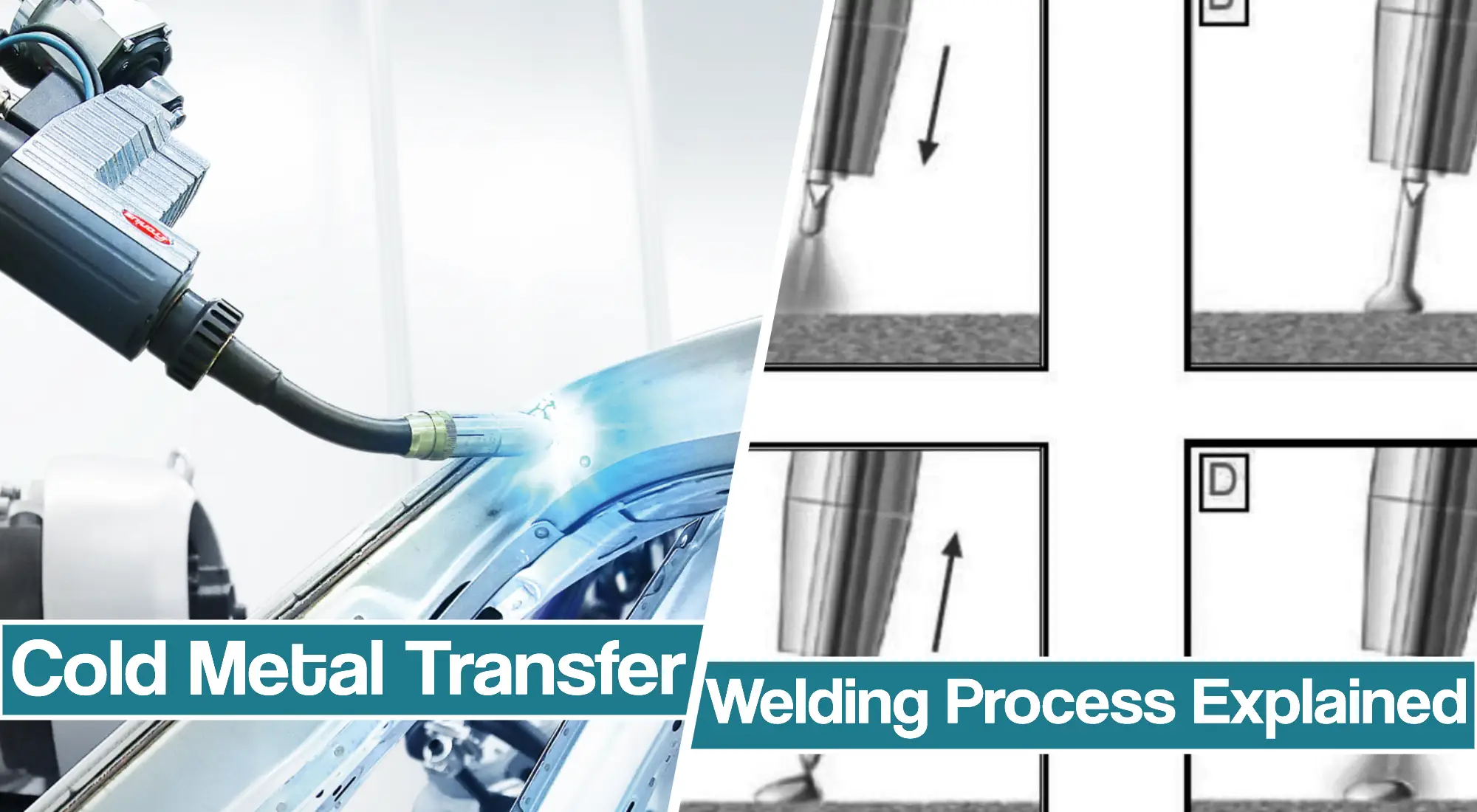

In a traditional setup, the wire hits the metal, creates a short circuit, and the heat explodes the droplet into the weld pool. It’s violent. It splashes. We call that spatter. Cold metal transfer changes the physical mechanics of how that wire moves. Instead of just pushing the wire forward and letting electricity do the heavy lifting, the CMT system actually pulls the wire back the exact millisecond a short circuit happens.

It’s a mechanical assist to an electrical process.

The Mechanical Secret Sauce

You’ve got to visualize the wire as a plunger. In standard dip-transfer welding, the wire moves in one direction: forward. When it touches the puddle, the current spikes, the wire melts, and the droplet detaches. But with cold metal transfer, the wire feeder is communicating with the power source at incredible speeds.

When the wire touches the molten pool, the digital controller says, "Stop."

Then it says, "Retract."

The wire physically pulls back. This mechanical retraction helps the droplet of molten metal detach into the pool without needing a massive surge of current. Because you aren't using that huge spike of electricity to "blow" the droplet off the wire, the overall heat input stays incredibly low. It’s precise. It’s clean. Most importantly, it’s repeatable in a way that old-school MIG just isn't when you're dealing with 0.8mm sheets.

Why the Automotive World Is Obsessed

If you look at a modern Audi or Mercedes, you’re looking at a jigsaw puzzle of aluminum and high-strength steel. Joining these two is a nightmare. They melt at different temperatures. They don’t like each other. If you use a standard arc, you get brittle intermetallic phases that snap like a dry twig.

Cold metal transfer made it possible to "braze-weld" these materials. Because the heat is so low, you can join galvanized steel to aluminum using a zinc-based filler wire. The steel doesn't even melt; only the filler does. This creates a bond that is remarkably strong but doesn't compromise the integrity of the base metals.

Engineers at companies like BMW started leaning heavily on CMT because it virtually eliminated spatter. Think about the cost of labor. If a robot welds a frame and covers it in tiny metal beads (spatter), a human has to go in there with a grinder and clean it up. That's a waste of time. CMT welds are often so clean they look like they were done by a laser.

It’s Not Just "Cooler" Welding

Let's get into the weeds of the pulse cycles.

In a typical CMT cycle, you have the arcing phase where the wire moves toward the workpiece. The arc heats up the metal. Then comes the short-circuit phase. This is the "cold" part. The arc is extinguished. The current drops to almost nothing. The wire retracts, the droplet drops, and the process repeats—up to 70 times per second.

🔗 Read more: Meaning of Emoji Symbols: Why Your Texts Keep Getting Misinterpreted

It’s a rhythm.

- The wire goes in.

- The system detects the touch.

- The current shuts down.

- The wire pulls back.

- The droplet stays in the puddle.

- The arc reignites.

This cycle is so stable that you can weld in positions that would normally be impossible. Overhead welding with thin material? Usually a recipe for molten metal dripping on your face. With cold metal transfer, the surface tension and the mechanical retraction keep the metal exactly where it belongs.

The Hardware Reality Check

You can’t just go to a hardware store and buy a "CMT nozzle" for your hobby welder. It doesn't work like that. The system requires a specialized wire drive—usually a "Push-Pull" torch—that has a tiny, high-speed motor right in the handle. This motor is what's doing the vibrating/retracting motion.

It's expensive. Honestly, for a small shop doing thick structural steel, it’s a total waste of money. You don't need CMT to weld a trailer hitch. But if you’re a Tier 1 supplier making battery enclosures for EVs? It’s basically mandatory.

The digital control units behind these machines are essentially high-powered computers. They are monitoring the arc length and the short-circuit duration in microseconds. If the gap between the wire and the metal changes because the part is slightly warped, the machine adjusts the wire speed and retraction frequency on the fly to compensate.

Where CMT Struggles

No technology is a magic bullet. While cold metal transfer is the king of thin materials and dissimilar metals, it can lack penetration on heavy-duty stuff. If you're trying to weld 20mm thick plate for a bridge, CMT isn't going to give you the "dig" you need. You need raw, unadulterated heat for that.

There's also the complexity factor. If the wire feed synchronization gets off by even a fraction, the whole process falls apart. It requires a level of maintenance and technical knowledge that goes beyond "point and shoot." You need operators who understand the software interfaces and can troubleshoot a dual-drive wire system.

Bridging the Gap: CMT and Additive Manufacturing

One of the coolest things happening right now with cold metal transfer is in 3D printing. Or, more accurately, Wire Arc Additive Manufacturing (WAAM).

Since CMT allows for such precise control of heat and metal deposition, it’s being used to "print" large metal parts. Instead of milling a giant block of titanium into a wing spar—and wasting 90% of the material—a robot arm equipped with a CMT head builds the part layer by layer. Because the heat is low, the part doesn't warp as it grows.

Researchers at Cranfield University have been pioneers in this, showing that CMT-based 3D printing can produce parts that are just as strong as forged ones but much faster to manufacture. It’s changing how we think about "making" things.

The Bottom Line on Cold Metal Transfer

So, what is it? It’s a marriage of electronics and mechanics. It’s a way to trick physics into letting us join metals that shouldn't be joined. It’s the difference between a rough, scorched seam and a perfect, silver bead.

📖 Related: iPhone Apps in App Store: Why You’re Probably Doing It Wrong

If you are looking to integrate this into a production environment, start by evaluating your "Buy-to-Fly" ratio or your scrap rate on thin alloys. If you're losing money on burn-through or post-weld cleanup, the investment in a CMT-capable system usually pays for itself in six to eighteen months.

Actionable Next Steps for Implementation

- Audit Your Material Thickness: If 80% of your work is above 6mm (1/4 inch), stick to traditional spray-transfer or pulsed MIG. CMT's value proposition peaks on materials between 0.5mm and 3.0mm.

- Evaluate Joint Gaps: CMT is incredibly "gap-bridging." If your fit-up is inconsistent, this technology can save parts that would otherwise be scrapped.

- Check Your Gas: While CMT works with standard Argon or CO2 mixes, using high-purity gases specifically tuned for low-heat transfer will maximize the "spatter-free" benefits.

- Consult a Robotic Integrator: CMT is rarely used as a manual process because humans can't stay as consistent as the software requires. If you're going CMT, you're likely going robotic.

- Test for "Brazing" Needs: If you're currently riveting or using adhesives to join steel to aluminum, run a CMT brazing trial. You might find a structural weld is actually faster and cheaper once the equipment is in place.