You’re probably holding a piece of ancient history every time you see a lump of charcoal’s distant, uglier cousin. It’s kinda wild to think about, but the energy powering your laptop or keeping the lights on in a massive skyscraper actually started as a soggy mess of ferns and giant mosses. We're talking about a timeline that makes the Roman Empire look like a blip on a radar screen. Coal formation isn't just some boring geology chapter; it’s basically nature’s way of pressure-cooking a swamp for 300 million years until it turns into a rock that burns.

Most people think coal comes from dinosaurs. It doesn't. That's a myth. Honestly, by the time the T-Rex was stomping around, most of the world's massive coal seams were already tucked away deep underground. The real stars of the show were trees that looked like something out of a low-budget sci-fi flick—scales instead of bark, no flowers, and heights reaching 100 feet. When these giants died, they didn't just rot away like a fallen branch in your backyard. They got buried. Fast.

The Carboniferous Period: Where It All Began

About 300 to 360 million years ago, Earth had a serious case of "swamp fever." This era is literally named the Carboniferous Period because of the sheer amount of carbon that got trapped in the crust back then. The planet was hot, humid, and covered in vast, shallow seas and coastal swamps. Imagine a place where the air is thick, the dragonflies are the size of seagulls, and the ground is basically a giant sponge.

📖 Related: Why The University of Alabama in Huntsville Huntsville AL is Quietly Dominating Deep Space Research

In these wetlands, plants grew at a breakneck pace. When they died, they fell into the water. Usually, when a plant dies, fungi and bacteria eat it, releasing CO2 back into the atmosphere. But in these stagnant, oxygen-poor swamps, the usual decay process just... stalled. The organic matter piled up. It became a thick, gooey layer of muck known as peat.

Peat is the "raw" stage of coal. You can still find it today in places like the bogs of Ireland or the Okefenokee Swamp in Georgia. If you dried it out and lit it, it would burn, but it’s smoky and inefficient. To get the high-energy stuff, you need the Earth to do some heavy lifting.

Heat, Pressure, and the Great Squeeze

Geology is mostly just a game of "what happens when you pile heavy stuff on top of other stuff." As sea levels shifted and the continents drifted, layers of sand, silt, and clay washed over those ancient peat bogs. This sediment is incredibly heavy.

This is where coal formation gets technical but also pretty cool. As the peat gets buried deeper—we're talking miles down—the weight of the overlying rock (lithostatic pressure) starts to squeeze out the water and gases. At the same time, the deeper you go into the Earth's crust, the hotter it gets. This combination of heat and pressure triggers chemical reactions that drive off oxygen and hydrogen, leaving behind a higher and higher concentration of carbon.

💡 You might also like: If I Delete a Message Does It Unsend? The Brutal Truth About Every Major App

It’s a slow transformation called coalification. It moves through specific ranks:

- Lignite: This is "brown coal." It’s soft, crumbly, and still has a lot of moisture. It’s better than peat, but it’s the "budget" version of coal.

- Sub-bituminous coal: A bit harder, a bit more carbon.

- Bituminous coal: This is the workhorse. It’s the most common type used for electricity and making steel. It’s dark, hard, and packs a punch in terms of energy.

- Anthracite: The "gold standard." It’s shiny, almost metallic-looking, and burns with a very clean, hot flame. It takes the most intense pressure and heat to create, which is why it’s usually found in mountain ranges where tectonic plates have smashed together.

Why the "Low Oxygen" Part is a Big Deal

If there was plenty of oxygen in those ancient swamps, we wouldn't have coal. We’d just have a lot of very fertile soil. The lack of oxygen is the "secret sauce" that preserves the carbon bonds. According to research from institutions like the United States Geological Survey (USGS), the preservation of this organic matter is a delicate balance of subsidence—the ground sinking—and the rate of plant growth. If the ground sinks too fast, the swamp becomes a lake, and the plants die off. If it sinks too slowly, the peat rots away. It had to be just right for millions of years.

There’s also a theory by some geologists, like those discussed in Nature Geoscience, suggesting that white-rot fungi (the stuff that eats wood) hadn't fully evolved yet during the early Carboniferous. If the fungi weren't there to break down the lignin in the wood, the peat just kept building up and up. It’s a bit of a debated topic, but it adds a layer of biological "luck" to why we have so much energy stored in the ground today.

Different Coal for Different Needs

Not all coal is created equal because the "ingredients" in the swamp weren't always the same.

👉 See also: What Does Double Space Mean? Why We Still Use It and How to Do It Right

- Some coal is "high sulfur" because the swamps were near saltwater.

- Some is "low ash" because it was formed from very clean plant matter.

- The Appalachian coal in the U.S. is famously different from the coal found in the Powder River Basin in Wyoming, mainly because of the specific age and geological stress each region went through.

The Reality of Our Energy Heritage

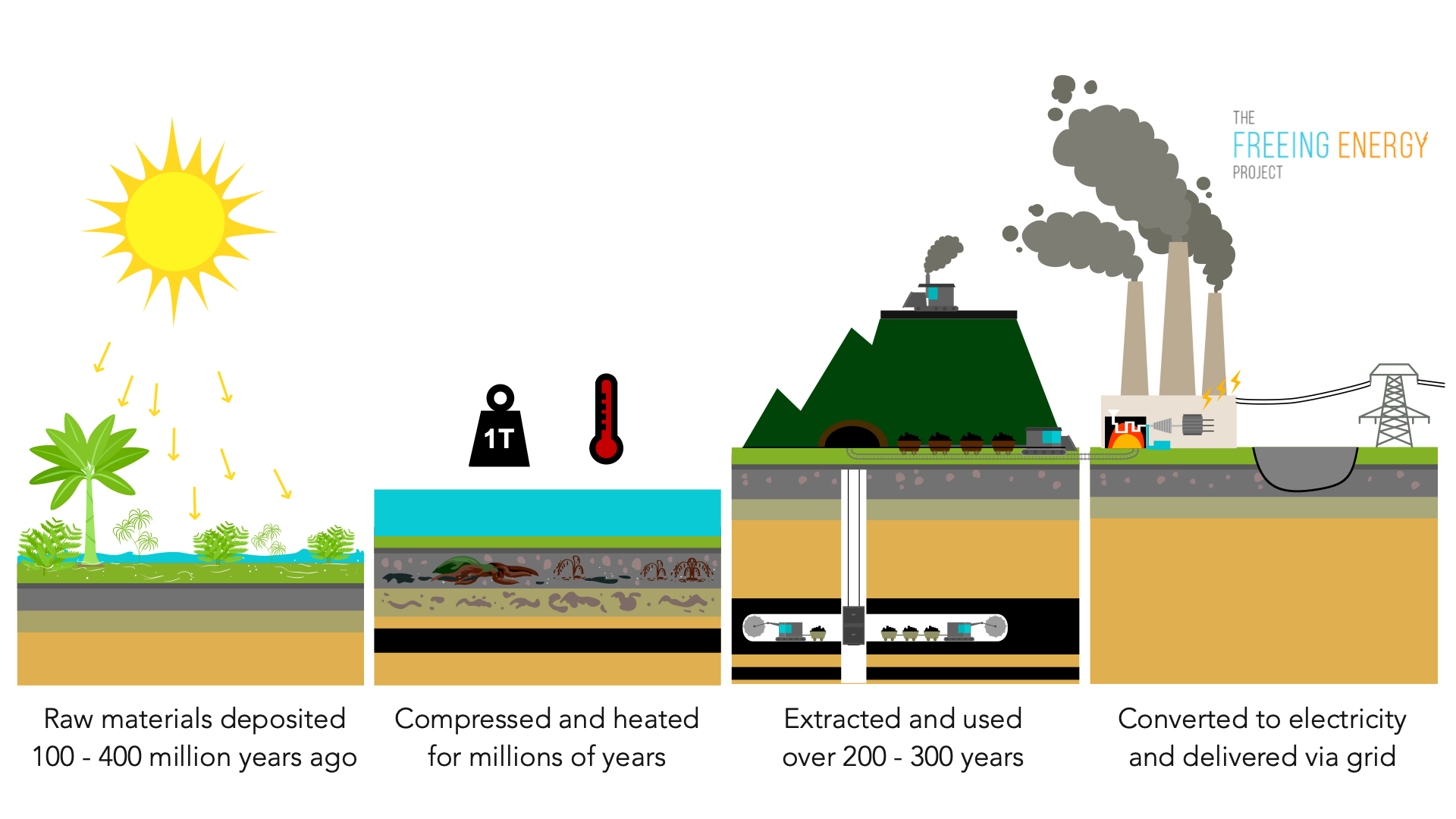

Understanding how coal is formed gives you a different perspective on the environment. We are essentially burning "fossilized sunlight." The energy released when you burn a piece of coal is the actual solar energy captured by a leaf 300 million years ago through photosynthesis. That’s a massive amount of time compressed into a single moment of combustion.

The downside, as we’ve learned over the last century, is that releasing 300 million years of stored carbon in just 150 years of industrialization has some heavy consequences for our atmosphere. It's a finite resource because the specific conditions of the Carboniferous Period—the massive scale of the swamps and the potential lack of wood-rotting fungi—aren't really happening on a global scale anymore.

Actionable Insights and Next Steps

If you're interested in the geological or economic impact of coal, here's how you can dig deeper:

- Check a Geologic Map: Look up your local state or regional geologic survey. You can see if you live over a "basin." If you’re in places like Pennsylvania, Illinois, or Queensland, Australia, you’re literally standing on top of ancient tropical swamps.

- Study Carbon Sequestration: Since we know how carbon gets trapped (the coal process), scientists are trying to do the reverse by pumping CO2 back into the ground. It’s a major field in "Green Tech" right now.

- Examine a Sample: If you can get your hands on a piece of bituminous coal, look closely with a magnifying glass. Sometimes, you can actually see the "macerals"—the microscopic remains of plant spores or cell walls frozen in the rock.

- Evaluate Energy Transitions: Follow the data on the Energy Information Administration (EIA) website to see how coal’s role in the global power grid is shifting toward natural gas and renewables.

The story of coal is really the story of Earth’s carbon cycle on overdrive. It’s a reminder that the ground beneath us is far from static; it’s a slow-motion pressure cooker that has been shaping the chemistry of our world long before we ever showed up to start the fire.