Cloud seeding controls the weather. It’s a phrase that makes some people think of mad scientists with giant remote controls and others think of desperate farmers praying for a drizzle. Honestly? Both are kinda wrong. We aren’t "controlling" the weather in the sense of playing God or flipping a switch to end a drought. It is way more subtle, a bit more frustrating, and a lot more scientific than the conspiracy theories suggest.

Think of the atmosphere as a sponge. Sometimes that sponge is dripping wet but just won't let go of the water. Cloud seeding is basically like walking up and giving that sponge a tiny squeeze. It doesn't create the water out of thin air. If the sky is clear and blue, you can blast all the silver iodide you want into the stratosphere and nothing—literally nothing—is going to happen. You need clouds to seed clouds.

How Cloud Seeding Actually Works (The Non-Sci-Fi Version)

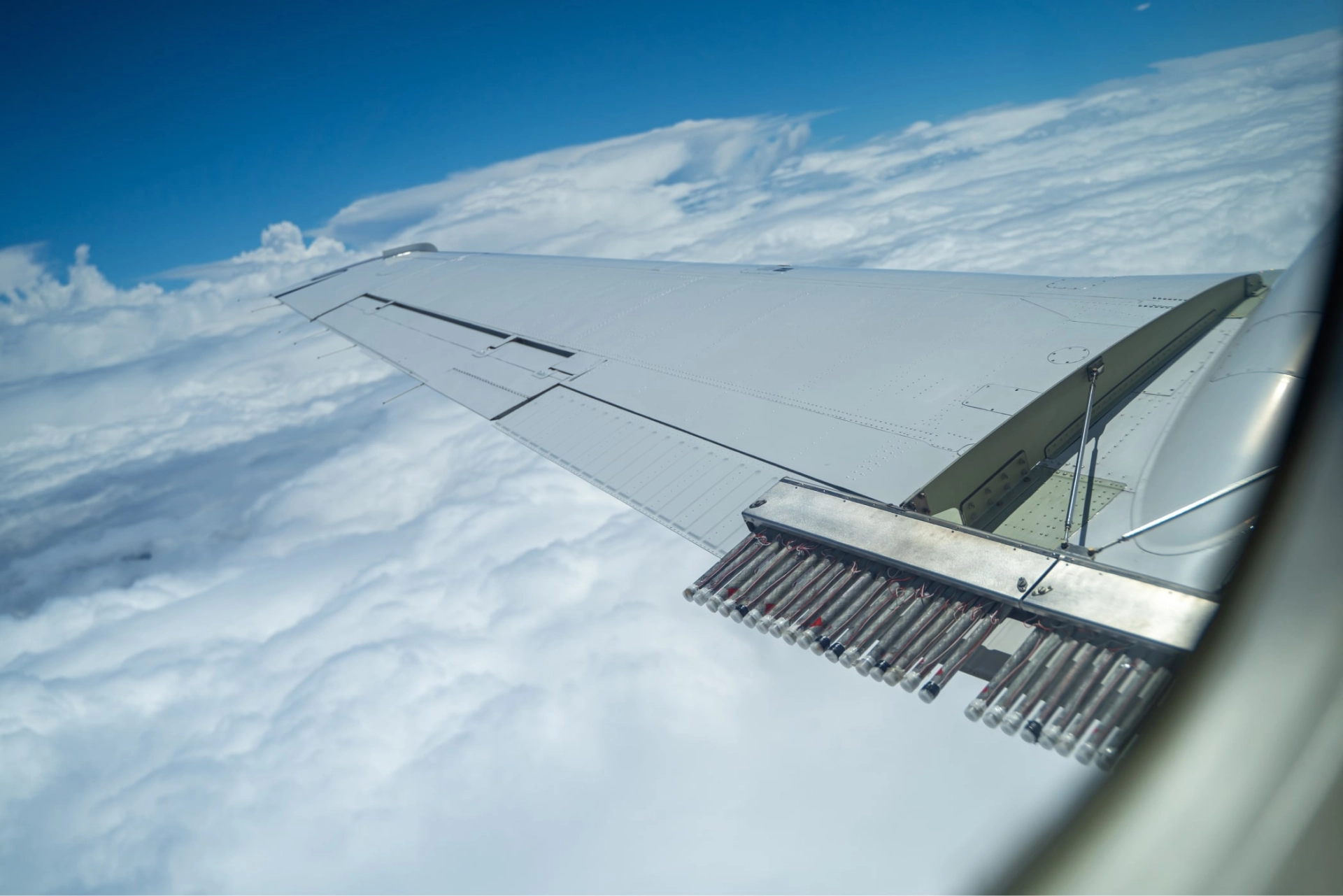

Basically, we're looking for "supercooled" liquid water. This is water that is colder than freezing but hasn't turned to ice yet because it lacks a nucleus—a little speck of something to grab onto. In nature, this might be a grain of dust or a bit of salt. In weather modification, pilots or ground-based "cannons" launch flares containing silver iodide or salt into the heart of a storm.

Silver iodide has a crystalline structure almost identical to ice. When those tiny particles hit the cloud, the supercooled water is tricked. It thinks, "Oh, hey, I'm ice now," and starts to crystallize. These crystals grow, get heavy, and eventually fall as snow or rain. It’s a nudge. A push. It is not a magical rain-maker that can turn the Sahara into a rainforest overnight.

The Dubai Debacle and the "Control" Myth

Remember the massive flooding in Dubai back in April 2024? Social media went absolutely nuclear. Everyone claimed that cloud seeding controls the weather so much that the UAE accidentally drowned itself. People were sharing clips of cars floating down highways like they were at a boat show.

The reality was much more boring. Meteorologists at the National Center of Meteorology (NCM) in the UAE confirmed that while they do seed clouds, they didn't seed that storm. Why? Because the storm was already a monster. It was a massive mesoscale convective system fueled by warming oceans and specific atmospheric pressure. Seeding a storm that big would be like throwing a cup of water into a swimming pool and claiming you caused the splash.

📖 Related: Min max normalization formula: Why your machine learning model is probably failing

Still, the narrative stuck. It’s easier to believe in a man-made disaster than to accept that our climate is becoming increasingly volatile and unpredictable on its own.

Why We Bother if it Isn't a Guarantee

You’ve probably wondered why states like Colorado, Utah, and California spend millions on this if it's so hit-or-miss. It’s about the "snowpack." In the American West, we don't just need rain; we need massive amounts of snow in the mountains to feed the rivers during the summer melt.

Studies by groups like the Desert Research Institute (DRI) and the Wyoming Weather Modification Pilot Program have shown that seeding can increase seasonal precipitation by about 5% to 15%. That sounds small. It is small. But when you’re talking about billions of gallons of water for the Colorado River, 10% is the difference between a functional economy and a total catastrophe. It’s a game of inches.

The Chemistry: Is Silver Iodide Poisoning Us?

This is the big one. If you’re spraying silver iodide into the air, isn't it eventually going to end up in our hair, our soil, and our sandwiches?

Scientists have been tracking this for decades. Silver iodide is used in such tiny, microscopic amounts that it’s nearly impossible to detect against the natural "background" levels of silver in the environment. We're talking parts per trillion. To put that in perspective, you’d probably get more exposure to heavy metals by touching an old nickel or walking down a busy city street than by standing in a seeded rainstorm.

Most researchers, including those from the North American Weather Modification Council, argue that the environmental impact is negligible compared to the massive benefit of increased water security. But, hey, skeptics exist for a reason. There’s always a lingering worry that messing with the natural order has a "butterfly effect" we don't fully understand yet.

The Ethical Mess: Stealing Rain?

If I seed a cloud over my farm in Idaho, am I stealing rain that was "supposed" to fall on my neighbor in Montana? This is where the idea that cloud seeding controls the weather gets legally hairy.

💡 You might also like: Galaxy Tab S9 Plus: What Most People Get Wrong

It’s called "cloud robbery" or "downwind effects."

For a long time, the consensus was that seeding actually increases efficiency and doesn't really take away from downwind areas. The idea was that clouds only release a fraction of their moisture anyway, so we’re just taking a slightly bigger sip of an enormous glass. However, as the technology gets better, the "rain theft" argument is gaining ground. If China—which has one of the largest weather modification programs on Earth—seeds clouds over the Tibetan Plateau, does that deprive downstream countries of the water they rely on? It’s not just science anymore. It’s geopolitics.

What’s Next for Weather Modification?

We are moving away from just airplanes and flares. The future is looking a lot more like "Star Wars."

- Electric Charges: Researchers in the UK have experimented with drones that release an electric charge into clouds to encourage droplets to collide and fall. No chemicals, just physics.

- Laser Pulses: There’s talk of using high-energy lasers to create plasma channels in the atmosphere that can trigger condensation. It's expensive and currently stuck in the lab, but it's on the horizon.

- Hygroscopic Seeding: This uses salt to make droplets bigger in warmer clouds, specifically for tropical areas where silver iodide doesn't work as well.

The technology is evolving from a blunt instrument to a scalpel. We aren't trying to change the climate—that's geoengineering, which is a whole different (and much scarier) ballgame involving mirrors in space or sulfur in the stratosphere. Cloud seeding is much more localized. It's a tool for water management, plain and simple.

Actionable Insights for the Weather-Curious

If you’re looking to understand how this impacts your local area or if you’re just a nerd for atmospheric science, here is how you can actually track this stuff:

👉 See also: Hydrogen Bond: The Science Behind Why Life Even Exists

Check your state’s Department of Natural Resources. States like Texas, California, and Wyoming have public records of when and where seeding operations occur. You can actually see the flight paths of the planes on sites like FlightAware if you know the tail numbers of the contractors (like Weather Modification Inc.).

Don't buy the hype on TikTok. If someone shows you a "square cloud" and says it's cloud seeding, they’re lying. Cloud seeding happens inside existing clouds; it doesn't create weird geometric shapes or neon-colored streaks in the sky. Those are usually just contrails or specific lighting conditions like "cloud iridescence."

Look at the SNOTEL data. If you live in the Western U.S., SNOTEL (Snow Telemetry) sites give you real-time data on snow water equivalent. You can see for yourself if the "seeded" seasons actually result in higher yields compared to historical averages.

We have to stop thinking about this as a conspiracy and start looking at it as a utility, like a water treatment plant or a power grid. It’s a human attempt to manage a resource that is becoming increasingly scarce. It isn't perfect, it isn't "control," and it definitely isn't magic. It's just a very expensive, very calculated way to squeeze a little more life out of a dry sky.

The next time it rains, don't worry about who "started" it. Just be glad the ground is getting a drink. Whether it was a natural fluke or a pilot with a flare, the water at the end of the day is still just water.