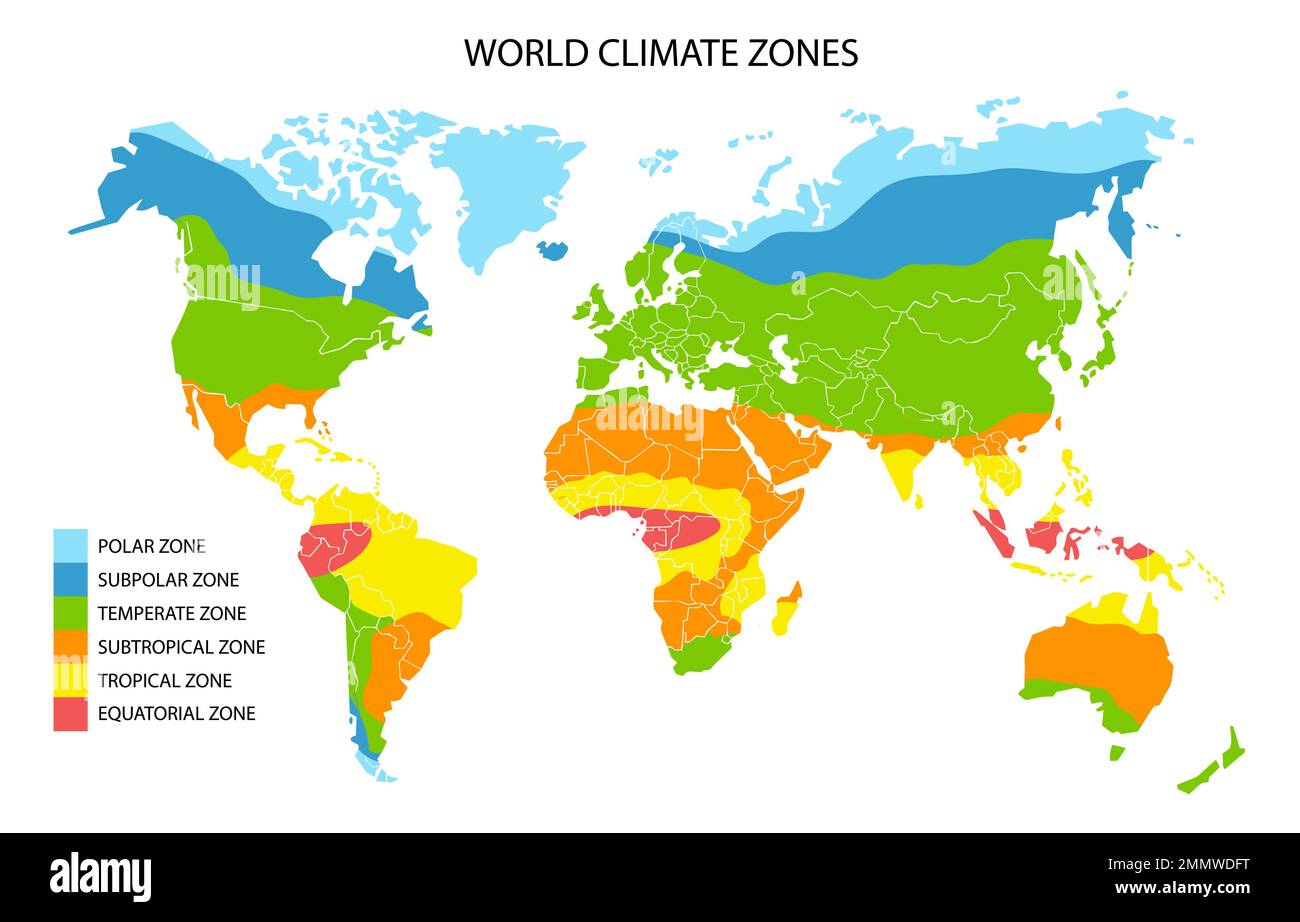

You probably remember that colorful poster on your fourth-grade classroom wall. It showed the world in neat, tidy slices. Green for the tropics. Yellow for the deserts. A big, icy blue cap for the poles. It looked simple. Easy. But honestly, if you look at a climate region map of the world today, you’ll realize that those neat little boxes are basically a fantasy. The world is much messier than that.

The climate isn't just "hot" or "cold." It’s a chaotic, swirling mess of moisture, pressure, and terrain. And it’s changing. Fast. If you’re planning a trip to the Mediterranean, you might expect dry summers, but what happens when the "climate" shifts two hundred miles north?

The Köppen-Geiger System: The Map We All Use (For Better or Worse)

Most maps you see online are based on the Köppen-Geiger classification. It was developed back in the late 1800s by Wladimir Köppen. Think about that. We are still using a system designed before airplanes existed to understand our modern world. It’s a bit weird, right? But it works because it relies on vegetation. Basically, Köppen realized that plants are the best meteorologists. If a palm tree can grow there, it’s a certain climate. If only lichen survives, it’s another.

The system breaks the world into five main groups. Group A is tropical. B is dry. C is temperate. D is continental. E is polar.

But here is where it gets crunchy.

Each of these has sub-categories. You've got your 'Af' which is tropical rainforest (always wet) and your 'Am' which is tropical monsoon. The map looks like a tie-dye shirt gone wrong. Most people get confused by the 'C' and 'D' regions. For instance, did you know parts of the American South are technically "Humid Subtropical," putting them in the same broad category as parts of Eastern China? It feels wrong when you're standing in a humid swamp in Georgia, but the data doesn't lie.

✨ Don't miss: What Time in South Korea: Why the Peninsula Stays Nine Hours Ahead

Why the Lines are Moving

Maps are static. The Earth isn't.

Since the 1980s, we’ve seen these climate borders literally crawl across the map. A study published in Nature confirmed that the tropics are expanding. They’re pushing north and south at a rate of about 30 to 60 kilometers per decade. That means the "dry" zones—the deserts—are shifting into areas that used to be temperate.

If you look at a climate region map of the world from 1950 and compare it to one from 2025, the "B" (Arid) zones are devouring the "C" (Temperate) zones in places like Spain and Turkey. It’s not just a subtle change. It’s a total regime shift for the people living there. Farmers who grew olives for generations are suddenly finding their soil is too dry, or the winter isn't cold enough to trigger fruit production.

The Mediterranean Misconception

Everyone loves the Mediterranean climate. It’s the gold standard for vacationing. Mild, wet winters and hot, dry summers. You find it in Italy, California, parts of Chile, and Western Australia. But travelers often get burned—literally—because they assume "Mediterranean" means "perfect."

Actually, these regions are some of the most volatile on the map. Because they sit right between the tropical heat and the temperate storms, a slight wobble in the jet stream sends them into chaos. Look at the wildfires in Greece or the droughts in Cape Town. The map says "Csa" (Hot-summer Mediterranean), but the reality feels more like a furnace.

🔗 Read more: Where to Stay in Seoul: What Most People Get Wrong

The "D" Zones: The Disappearing Winters

Let’s talk about the Continental climates. These are the "D" regions on your climate region map of the world. Think Chicago, Moscow, or Toronto. These are defined by having at least one month of freezing temperatures and at least one month above 10°C.

They are shrinking.

In many parts of New England and Eastern Europe, the "D" zones are being replaced by "C" zones. Winters are getting shorter. The "line of frost" is retreating toward the poles. For a traveler, this might mean less snow for your ski trip. For a biologist, it means invasive pests that used to die off in the winter are now surviving and killing off local forests. It's a domino effect that a simple color-coded map can't really capture.

Mountain Climates: The Map’s Greatest Failure

One thing you’ll notice on a high-quality climate map is the "H" category for Highlands. Or sometimes, the map just ignores mountains entirely and colors them based on the base elevation. This is a huge mistake.

Mountains create their own weather. You can start in a tropical jungle at the base of the Andes and end up in a polar wasteland at the summit, all within a few miles. This is called altitudinal zonation.

💡 You might also like: Red Bank Battlefield Park: Why This Small Jersey Bluff Actually Changed the Revolution

- Tierra Caliente: Hot land (the base).

- Tierra Templada: Temperate land (where most people live).

- Tierra Fría: Cold land (high crops like potatoes).

- Tierra Helada: Frozen land (above the tree line).

When you look at a global map, these are often just slivers of grey or brown. But for a third of the world's population, these vertical "micro-climates" are more important than the broad regional ones.

How to Actually Use This Information

If you’re looking at a climate region map of the world to plan your life or your next big trip, don't just look at the colors. Look at the trends.

The most reliable source for the most up-to-date mapping is the Beck et al. (2018) high-resolution Köppen-Geiger maps. They use recent data from 1980–2016 rather than the old 1900s datasets. You can see the pixelated shifts where the "dry" line is moving.

Actionable Insights for the Savvy Map-Reader:

- Check the "s" vs "w": In the Köppen system, 's' means dry summer, 'w' means dry winter. This matters immensely for travel. If you go to a 'Aw' (Tropical Savanna) region in the winter, it’s beautiful. Go in the summer, and you’ll be stuck in a monsoon.

- Look for Elevation: If the map doesn't show topographical shading, overlay it with a physical map. A "Temperate" zone at 5,000 feet is a completely different beast than one at sea level.

- Watch the Permafrost: If you’re looking at the "E" (Polar) regions, recognize that these are the most unstable. The "Tundra" (ET) is currently turning into "Subarctic" (Dfc) as the ice melts and shrubs move in.

- Use Dynamic Tools: Sites like Global Forest Watch or the IPCC Interactive Atlas allow you to see how these climate regions are projected to look in 2050. It’s scary, but it’s more accurate than your old textbook.

Stop thinking of climate regions as permanent borders. They are more like shifting tides. The map is just a snapshot of a world in motion. If you want to understand where the world is going, you have to stop looking at where the colors used to be and start looking at where they are bleeding into each other.