You pull the cord. Nothing. You pull it again, harder this time, and maybe you get a half-hearted sputter before the engine dies with a pathetic wheeze. It’s frustrating. Most people assume the spark plug is shot or the engine is "blown," but honestly, it’s almost always the fuel. Specifically, it’s the gunk inside the bowl. Cleaning a small engine carburetor is the one skill that separates people who buy a new weed whacker every three years from people who keep the same Honda mower running for two decades.

Modern gasoline is mostly to blame. Ethanol attracts moisture. Over time, that watery mix sits in your fuel lines and turns into a sticky, varnish-like shellac. It clogs the tiny passages—called jets—that are responsible for mixing air and fuel. If those holes are blocked, your engine starves. It’s like trying to drink a thick milkshake through a pinched straw.

It sucks. But it's fixable.

The anatomy of a dirty carb

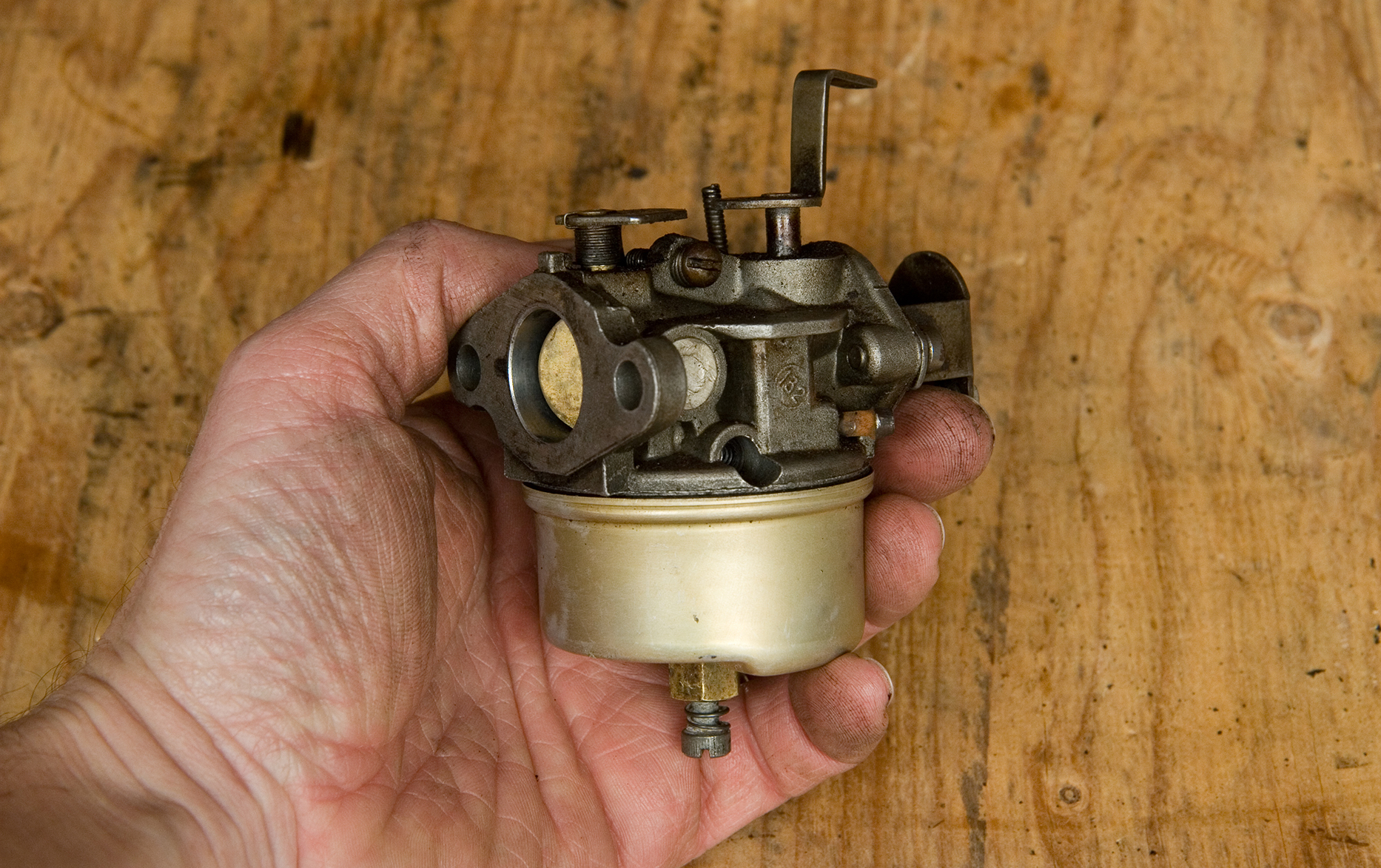

Before you start ripping screws out, you have to understand what you're looking at. Most small engines, whether they’re on a Briggs & Stratton, Tecumseh, or Kohler, use a float-style carburetor. It’s a simple mechanical device. Gravity or a small pump pushes gas into a bowl. A plastic or brass float sits in that gas; when the bowl is full, the float rises and pushes a needle into a seat to shut off the flow.

When you're cleaning a small engine carburetor, you’re mostly fighting "varnish." Varnish is just old gas that has evaporated and left behind a crusty residue. This residue loves to hide in the emulsion tube. That’s the long brass piece with holes in the side that sits right in the center of the carb. If those tiny side-holes are plugged, the engine will "hunt" or "surge"—that annoying vroom-wow-vroom-wow sound you hear when the governor is trying to keep the RPMs steady.

Tools you actually need

Don't just grab a pair of pliers and a prayer. You need real carb cleaner—the nasty stuff in the aerosol can. Brands like Gumout or Berryman B-12 Chemtool are the industry standards for a reason. They dissolve the resins that soap and water won't touch. You also need a set of "torch tip cleaners" or a very thin piece of copper wire.

Stay away from steel wire if you can. Steel is harder than the brass used in carburetors. If you’re too aggressive, you’ll accidentally enlarge the jet hole, and then the engine will run "rich," puffing black smoke and wasting fuel. A single strand from a frayed throttle cable or a piece of thin copper wire stripped from an old electrical cord is usually perfect.

Taking it apart without losing your mind

First, take a picture. Seriously. Take ten pictures. The linkage—those tiny springs and metal rods connecting the carburetor to the throttle—is a geometric nightmare. You think you’ll remember how the "Z-bend" goes into the plastic arm, but three hours later, you won't.

Once the air filter housing is off, you’ll usually find two long bolts holding the carb to the engine block. Slide the unit off. Be careful with the gaskets. If the paper gasket tears, you’re going to have a vacuum leak. A vacuum leak is the silent killer of small engine repair. It lets "unmetered" air into the engine, making it run lean, hot, and erratic. If it tears, don't try to "RTV" or glue it back together. Just buy a new one. They’re five bucks.

The bowl and the needle

The bottom of the carb is the "bowl." There’s usually a 10mm or 1/2-inch bolt holding it on. This bolt is often the "main jet" itself. Notice if there are holes in the threads of that bolt. Those have to be crystal clear.

🔗 Read more: Old Fashioned Sour Cream Cookies Are The Best Recipe You Probably Forgot About

Pop the bowl off. If you see green crust or what looks like white sand, that’s corrosion from ethanol. It's nasty. Pull the pin that holds the float in place. Under the float, you’ll find the needle. The tip of that needle is usually made of Viton (a synthetic rubber). If there’s a ring worn into the rubber tip, it won’t seal. It’ll leak gas into your oil, which is a much bigger problem.

The actual cleaning process

Spray everything. Every hole, every orifice, every dark corner. Wear safety glasses. I’ve seen enough people take a direct hit of carb cleaner to the eyeball to know that it’s a day-ender.

The main goal when cleaning a small engine carburetor is to ensure that every passage is "clear to light." This means you should be able to hold a jet up to a bright window and see a perfect circle of light through the center. If it’s fuzzy or lopsided, keep poking.

- The Emulsion Tube: This is the most skipped step. Often, the tube is pressed into the center column. You might need to gently tap it out with a screwdriver. It has tiny holes along its length. These holes atomize the fuel. If they are blocked, the engine might start but will die as soon as you put it under a load (like hitting tall grass).

- The Pilot Jet: On many modern carbs (especially Hondas and their clones), there’s a small plastic or brass screw on the top or side. This controls the idle. If your mower starts with the choke on but dies as soon as you turn the choke off, your pilot jet is clogged. Use your thinnest wire here.

- The Bowl Vent: There’s always a small hole that lets the bowl "breathe." If this is clogged, a vacuum forms inside the carb and the fuel can't flow. It's like trying to pour water out of a jug without a vent hole.

Ultrasonic cleaners: Overkill or essential?

If you do this a lot, get a cheap ultrasonic cleaner. Fill it with a mix of Simple Green Pro HD (the purple stuff) and water. Dropping a stripped-down carb body into a heated ultrasonic bath for 20 minutes does a better job than four cans of spray. It reaches the internal galleries that a wire can't touch. But for a one-time fix, the aerosol can and a steady hand are fine.

Reassembly and the "Static" test

Dry everything with compressed air if you have it. If not, let it air dry. Put the needle and float back in first. Before you put the bowl back on, do a quick test. Hold the carb upright and blow into the fuel inlet nipple. Air should pass through. Now, flip the carb upside down so the float "closes." Blow again. No air should get through. If it does, your needle isn't seating, and your carb will leak.

Reinstall the carb on the engine. Hook up those linkages—check your photos! Ensure the governor arm moves freely. If it binds, the engine will scream at dangerously high RPMs the moment it starts.

A note on "Magic" fixes

You’ll see products like Sea Foam or Mechanic in a Bottle. Do they work? Sorta. They are great as a preventative measure or for very light cleaning. But if your carb is full of solid varnish, no chemical you pour in the gas tank is going to fix it. You have to get in there and physically move the dirt. It’s a mechanical problem, not a chemical one.

Why this keeps happening

If you want to avoid cleaning a small engine carburetor every spring, change your habits.

- Fuel Stabilizer: Use it every time you fill your gas can, not just at the end of the season.

- Ethanol-Free Gas: If you can find it (often labeled as Rec-90), use it. It doesn't degrade nearly as fast as the 10% ethanol stuff at the pump.

- Drain the bowl: Most carburetors have a small drain screw on the bottom. If you’re storing the tool for more than a month, turn the fuel valve off and drain the bowl. If there’s no gas in the carb, there’s no gas to turn into varnish.

Troubleshooting the "Non-Starter"

If you’ve cleaned the carb and it still won't start, check the "sheared flywheel key." If you hit a rock recently, the timing might be off. But 90% of the time? It was the carb. If you’ve cleaned it and it still runs poorly, you might have an air leak between the carb and the engine. Spray a little starting fluid around the gaskets while it’s running. If the engine RPM changes, you’ve found your leak.

Actionable Next Steps

- Inspect your fuel lines: If they are hard, brittle, or "crunchy," replace them immediately. Tiny bits of degrading rubber from the inside of the hose will clog your newly cleaned carb in minutes.

- Check the tank: Look inside your gas tank with a flashlight. If you see flakes of rust or dirt, you must flush the tank. Cleaning the carb is useless if the tank is sending more junk down the line.

- Replace the fuel filter: Many people don't even realize their small engine has an in-line filter. If yours is dark or opaque, swap it out.

- Buy a spare carb: Honestly? For many common engines like the Honda GX160 or the Briggs 500 series, a brand-new "aftermarket" carburetor costs $15 to $25 on the internet. If yours is heavily corroded, sometimes it's more cost-effective to just replace the whole unit and keep the old one for parts.

Keeping your equipment running doesn't require a degree in mechanical engineering. It just requires a little patience, a can of solvent, and the willingness to get your hands a bit greasy. Most of these machines are remarkably resilient; they just want to breathe. Clear the path for the fuel, and they'll usually reward you with a first-pull start.