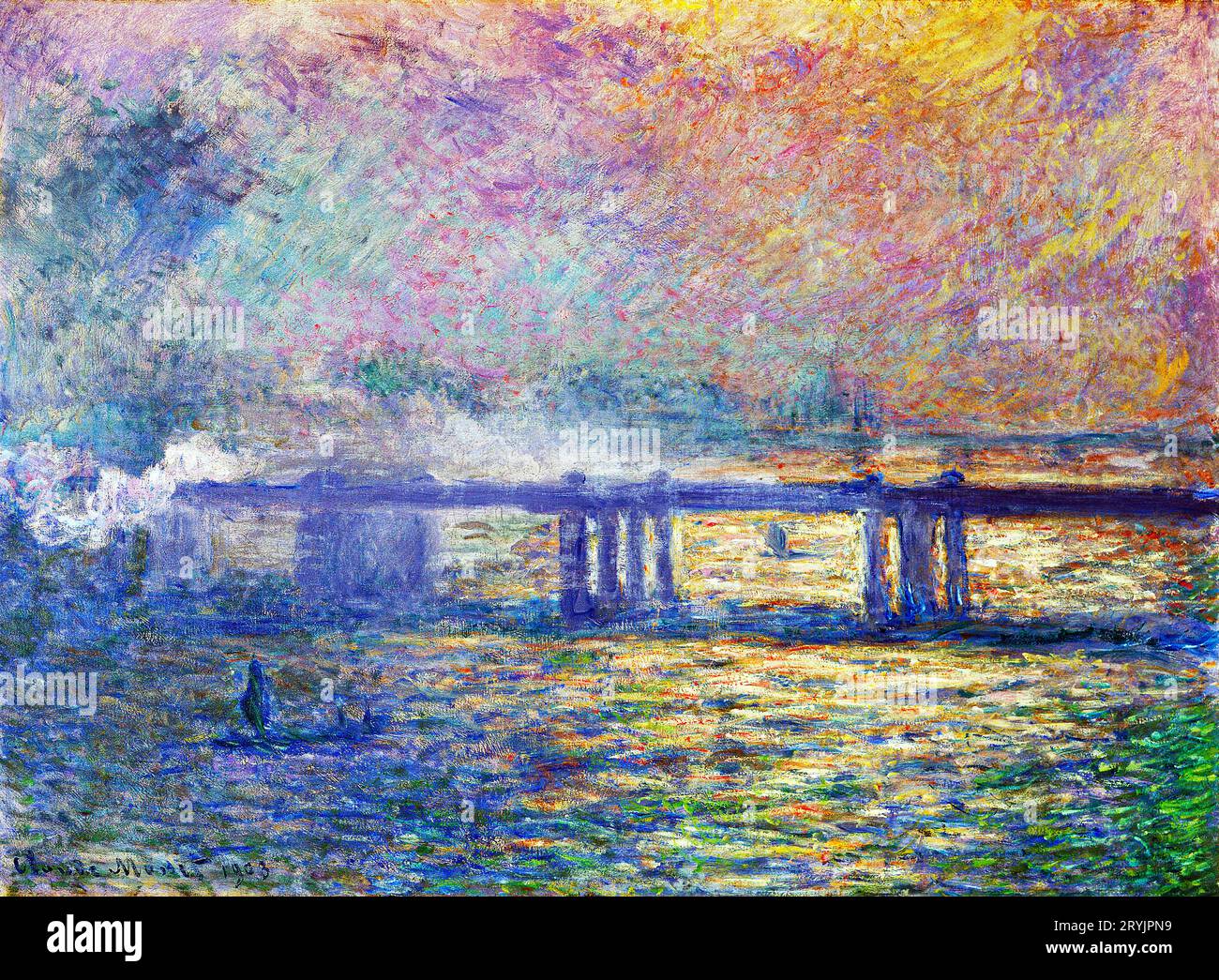

London was a nightmare in 1899. It was filthy. A thick, yellow-black "pea-souper" fog choked the streets, a mix of coal smoke and river damp that honestly sounded miserable to live in, but for Claude Monet, it was perfect. He didn't come for the architecture. He came for the atmosphere. When you look at a Charing Cross Bridge painting today, you aren't really looking at a bridge. You're looking at the air itself.

Monet was obsessed. He stayed at the Savoy Hotel, bagging a room with a balcony that gave him a direct line of sight to the South Eastern Railway bridge. He didn't just paint it once. He painted it nearly 40 times. It’s wild to think about a world-famous artist just sitting there, day after day, waiting for the sun to hit the smog at just the right angle to turn the mud-brown Thames into a shimmering violet or a ghostly green.

The Industrial Beauty of the Charing Cross Bridge Painting

Most people think Impressionism is all about lily ponds and pretty gardens in Giverny. That’s only half the story. Monet was actually fascinated by the industrial grit of the late 19th century. The Charing Cross Bridge was a symbol of "modern" London—clunky, iron-heavy, and constantly vibrating with the sound of steam trains.

But look at the canvases. The bridge is almost a ghost.

In some versions, like the one held by the Saint Louis Art Museum, the bridge is nothing more than a dark, rhythmic streak cutting through a haze of pink and blue. Monet wasn't interested in the rivets or the engineering. He wanted the enveloppe—the term he used for the light and the air surrounding the object. He once famously said that without the fog, London wouldn't be a beautiful city. It was the "smog" (though they didn't call it that then) that gave the city its mystery.

👉 See also: Sleeping With Your Neighbor: Why It Is More Complicated Than You Think

Why Monet Kept Messing With the Same View

Why 37 versions? It seems like overkill. But if you’ve ever looked at the Thames on a cloudy day, you know the color changes every thirty seconds.

Monet would have multiple canvases going at once. He’d work on one for fifteen minutes until the sun shifted, then ditch it for another one that matched the new light. It was a frantic, high-stakes game of "catch the color." He wasn't just a painter; he was a scientist of optics.

There's this great story about him getting frustrated because the fog would clear up too fast. He wanted the gloom. When the sun came out, he basically stopped working. For Monet, the Charing Cross Bridge painting series was an exercise in seeing the invisible. He wanted to prove that color isn't a fixed thing. A red bus isn't red if the light is blue; it’s a muddy purple. He was obsessed with that truth.

The Mystery of the Finishing Touches

Here is something most people get wrong about these paintings: they weren't all finished in London.

✨ Don't miss: At Home French Manicure: Why Yours Looks Cheap and How to Fix It

Monet took the canvases back to his studio in Giverny. He spent years—literally years—tweaking them. He’d look at the whole series together, trying to make sure the "mood" of one flowed into the next. This actually sparked some controversy among art purists. Some felt that by finishing them in a studio years later, he was "cheating" the Impressionist rule of painting en plein air (in the open air).

But honestly, who cares? The result is a dreamscape. By the time he was done in 1904, the paintings had become less about a specific day in London and more about a feeling of isolation and ethereal beauty.

Seeing the Series Today

You can find a Charing Cross Bridge painting in almost every major art hub.

- The Art Institute of Chicago has a stunning version with heavy, saturated blues.

- The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston holds a version where the sun is a pale, glowing disc struggling to break through the smoke.

- The National Museum of Wales has a particularly "golden" version.

If you ever get the chance to see two or three of these in the same room, do it. You’ll notice how the bridge stays in the same spot, but the world around it vibrates. It’s like watching a time-lapse video made of oil paint.

🔗 Read more: Popeyes Louisiana Kitchen Menu: Why You’re Probably Ordering Wrong

The Scientific Side: Was it Just Art or Real Pollution?

Interestingly, researchers have actually used Monet's London series to study the historical air quality of the city. A study by researchers at the University of Birmingham and Durham University looked at the "spectral composition" of the light in his paintings.

They found that Monet was actually a very accurate "proxy" for 19th-century air pollution. The specific oranges and greys he used correspond with the way light scatters when it hits high concentrations of sulfur dioxide and soot from coal fires. So, while he thought he was painting "beauty," he was also documenting one of the biggest environmental disasters of the Victorian era. It's a weird mix of high art and climate data.

The Legacy of the Fog

Monet’s London series, and the Charing Cross paintings specifically, changed how we see cities. Before him, cityscapes were usually crisp, clear, and focused on the majesty of buildings. Monet made us look at the "nothingness" between the buildings. He taught us that there is beauty in the blur.

He didn't want to show you what the bridge looked like; he wanted to show you how it felt to stand on the banks of the Thames at 8:00 AM on a Tuesday when you couldn't see your own hand in front of your face.

Actionable Ways to Experience Monet's London Today

If you're a fan of art history or just like the vibe of these paintings, don't just look at them on a screen. Here is how to actually engage with the history:

- Visit the Savoy Hotel's River Side: You can’t get into the exact rooms easily without a reservation, but the view from the Victoria Embankment nearby is almost identical to Monet's perspective. Stand there at sunset during a drizzly autumn day. You'll see exactly what he saw—the way the Waterloo Bridge and Charing Cross Bridge become silhouettes against the grey-blue water.

- Compare the Series Online: Use the Google Arts & Culture tool to zoom into the brushstrokes of different versions. Look at the "Charing Cross Bridge" in the National Gallery of Art (DC) versus the one in the Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum (Madrid). The difference in the thickness of the paint (impasto) tells you how much he was struggling with the light that day.

- Read his letters: Pick up a copy of Monet: Nature into Art or search for his translated letters from London. He complains about the weather constantly, and it’s deeply relatable. It humanizes a "master" to hear him whine about the "frightful" London fog while simultaneously trying to paint it.

- Check Local Galleries: These paintings travel a lot. Because there are so many in the series, they are often loaned out for "Impressionism in the City" exhibitions. Check the upcoming schedules for your nearest major metropolitan museum; there is a high statistical chance a Charing Cross version is nearby.

The real magic of the Charing Cross Bridge painting isn't in the bridge itself. It's in the realization that even a grimy, industrial railway can be a masterpiece if you look at it through the right light. Monet didn't ignore the soot; he made it glow.