You’ve seen them in movies. A dusty blue line of soldiers marches across a field, and right in the middle, there’s a massive, silk flag whipping in the wind. It’s a powerful image. But honestly, most of those Hollywood props are wrong. If you look at real civil war union flags from the 1860s, they don't look like the crisp, standardized banners we fly on the Fourth of July today. They were chaotic. They were handmade. And surprisingly, they were often the most dangerous thing a soldier could carry.

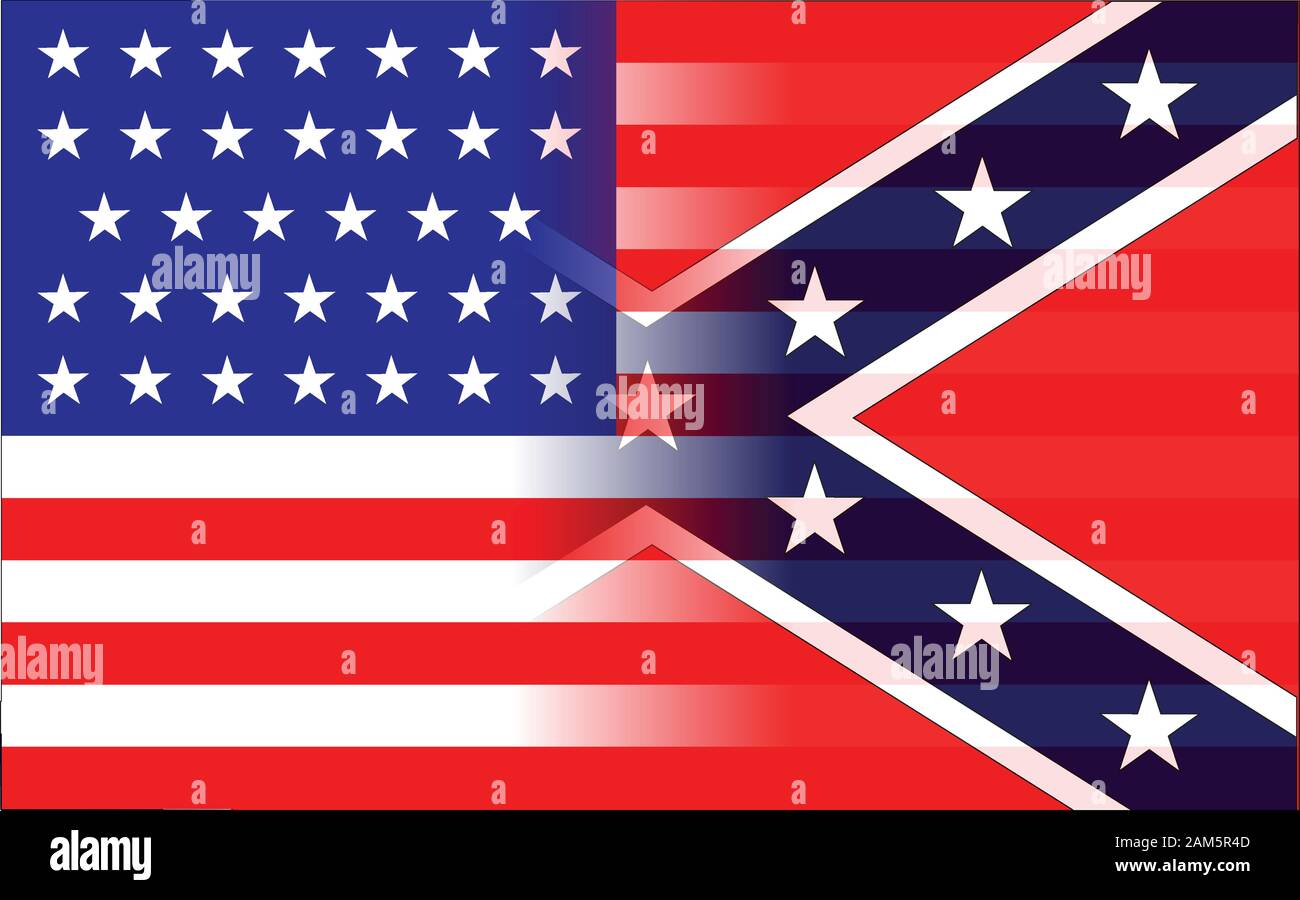

The American flag changed constantly during the war years. It’s kinda wild to think about, but the United States was adding states even while it was tearing itself apart. When the war kicked off in 1861, the official flag had 33 stars. By the time it ended, that number had jumped. But here’s the kicker: even though the South had seceded, Abraham Lincoln flat-out refused to remove their stars from the flag. To him, the Union was legally unbroken. Removing a star would be admitting the Confederacy was its own country. So, the "Old Glory" carried by Northern regiments always represented a whole nation, even if half of it was trying to leave.

The 34-Star Flag and the Kansas Problem

Kansas joined the Union in January 1861. That meant the 33-star flag was technically outdated almost as soon as the first shots were fired at Fort Sumter. On July 4, 1861, the 34-star flag became the official version. This is the flag most people associate with the early years of the conflict.

You might think the government sent out a "standard" design to every unit. Nope. The Army didn't really have a strict rule about how the stars had to be arranged. This led to some beautiful, bizarre designs. Some flags had the stars in a circle—a "Medallion" pattern. Others had them in a "Great Star" design, where the small stars were arranged to form one giant star. Some were just rows. If you were a seamstress in 1862, you basically had creative license.

Then came West Virginia in 1863, followed by Nevada in late 1864. Each time, a star was added. By the end of the war, the "official" count was 35, then 36. But supply lines were slow. You’d have units fighting in 1865 under a 34-star flag because their 36-star replacement was stuck on a train in Ohio. It was a mess.

Why Carrying the Flag Was a Death Sentence

Being a color bearer was the most prestigious job in a regiment. It was also a great way to get shot.

Flags weren't just for show; they were the 19th-century version of a GPS and a radio. In the middle of a battle, you couldn't hear anything. The roar of thousands of muskets and the "shriek" of Parrott rifles created a wall of sound. Smoke from black powder was so thick you couldn't see five feet in front of you. The only way a soldier knew where his unit was—or which way to move—was by looking for that high-flying flag.

Because the flag was the "brain" of the unit, the enemy prioritized killing the guy holding it. If the flag went down, the regiment might panic. At the Battle of Gettysburg, the 24th Michigan lost nine color bearers in a single day. Nine men, one after another, stepped up to grab the staff as their friends were gunned down. It sounds insane to us now. But back then, letting the flag touch the dirt was the ultimate disgrace.

The Regimental Colors vs. The National Colors

Most Union infantry regiments actually carried two flags.

- The National Color: This was the Stars and Stripes. It was usually made of silk and featured the regiment’s name embroidered in gold on the red stripes.

- The Regimental Color: This was usually a solid blue field with an eagle clutching arrows and an olive branch. It often had the U.S. coat of arms.

These flags were massive—usually six feet by six feet. Imagine trying to run through a swamp or a thicket of Virginia pine while holding a heavy wooden pole topped with 36 square feet of wet silk. It was a physical nightmare.

The Secret Language of Battle Honors

If you ever get the chance to see an original civil war union flags collection in a museum, like the ones at the National Museum of American History, look closely at the stripes. You’ll see names painted on them: Antietam, Fredericksburg, Chancellorsville, Gettysburg. These weren't just decorations. These were "Battle Honors." General Orders No. 19, issued in 1862, allowed regiments to write the names of battles they fought in on their flags. It was a huge point of pride. A flag covered in names told everyone that this was a veteran unit that had seen the worst of the war.

Some flags are also riddled with holes. Veterans would often refuse to patch them. Those "bullet-rent" holes were proof of bravery. After the war, during "Return of the Colors" ceremonies, many soldiers wept as they handed these tattered rags over to state governments for safekeeping. They weren't just pieces of cloth; they were the "soul" of the men they'd lost.

Myths and Misconceptions

People love to talk about the "Fringe." You'll hear conspiracy theorists today say that gold fringe on a flag means "maritime law." That is total nonsense. In the 1860s, gold fringe was just a decorative touch used on parade flags or those kept in a general’s office. It didn't have a legal meaning. It just looked fancy.

Another big one? The idea that every flag was made of wool. Most high-end battle flags were silk. Wool was used for the big flags flying over forts—like the massive garrison flag at Fort Sumter—because wool holds up better in the wind and rain. But for the flags carried by soldiers, silk was preferred because it was lighter and looked better in the sun.

How to Identify a Real Civil War Union Flag

If you’re a collector or just a history buff, spotting an authentic flag is tough.

- Check the Material: Real ones are almost always silk or wool bunting. If it feels like modern polyester, it’s a fake.

- Look at the Stars: Are they perfectly symmetrical? They probably shouldn't be. Hand-sewn stars often have slight variations in shape or "tilt."

- The Hoist: The part that attaches to the pole should be heavy canvas, often with hand-worked buttonholes rather than metal grommets. Metal grommets didn't really become standard until later in the 19th century.

- The Size: Authentic infantry flags were roughly 6'x6'. If you find a tiny one, it might be a "camp color" or a guidon used by the cavalry.

Why This Matters Today

The Civil War was the moment the United States shifted from being a collection of states to a single nation. Before 1861, people said "The United States are..." After 1865, they said "The United States is..."

✨ Don't miss: Random Phone Numbers Prank Call: Why This Old School Habit Is Getting People Arrested

Those flags are the physical evidence of that shift. They represent the high cost of that "is." When you look at a 35-star flag, you’re looking at a map of a country trying to find its identity in the middle of a graveyard. It’s heavy stuff.

Practical Steps for History Enthusiasts

If you want to dive deeper into the world of civil war union flags, don't just look at Google Images.

- Visit State Capitols: Many Northern states (like Pennsylvania and Michigan) have incredible, climate-controlled "Flag Rooms" where they keep the original banners returned by the regiments.

- Consult the Experts: Look for books by Howard Madaus or Grace Rogers Cooper. They are the legends of "Vexillology" (the study of flags).

- Check the "Civil War Trust": Now known as the American Battlefield Trust, they often have digital archives showing exactly which flags were at which battles.

- Volunteer for Conservation: Many of these flags are literally falling apart. Silk "shatters" over time due to old dyes. Supporting textile conservation is the only way these artifacts will survive another hundred years.

Understanding these flags is about more than just counting stars. It's about recognizing the literal "guidelines" that kept men moving forward when everything else was falling apart. Next time you see one in a museum, look for the small details—the uneven stitching, the faint bloodstains, or the name of a small town in Tennessee painted on a red stripe. That's where the real history is.