In the early 90s, Chicago was struggling. Violent crime was hitting record highs, and many neighborhoods felt like they were under siege by street gangs. The city council decided they’d had enough. They passed the Gang Congregation Ordinance, a law designed to give police the power to clear the streets before trouble even started. It seemed like a common-sense solution to a desperate problem. But then the Supreme Court stepped in. City of Chicago v. Morales changed the game for how cities can police "vagrancy" and "loitering."

It wasn't just about gangs. It was about whether the government can tell you to move along simply because a cop thinks you look suspicious.

What was the Gang Congregation Ordinance?

The law was pretty straightforward, at least on paper. If a police officer observed a person they "reasonably believed" to be a member of a criminal street gang loitering in a public place with one or more other persons, they could order everyone to disperse. If you didn’t move, you went to jail.

Simple, right? Not exactly.

The problem was the definition of "loitering." The city defined it as "remaining in any one place with no apparent purpose." Think about that for a second. Have you ever stood on a street corner waiting for a friend who was late? Or stopped to enjoy a breeze on a hot summer day? Under this law, if a cop decided you had "no apparent purpose," you were breaking the law. Between 1992 and 1995, Chicago police arrested over 42,000 people under this ordinance. That is a staggering number of people losing their liberty because a police officer couldn't see why they were standing on a sidewalk.

🔗 Read more: Johnny Somali AI Deepfake: What Really Happened in South Korea

The Legal Battle Begins

Jesus Morales was one of those people. He was arrested and charged under the ordinance, but he didn't just pay a fine and move on. He challenged the constitutionality of the law. The case worked its way through the Illinois court system, with the Illinois Supreme Court eventually striking it down. Chicago wasn't giving up, though. They took it all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court in 1998.

The city argued that the law was a necessary tool to prevent crime. They claimed that gang members used loitering to intimidate residents and establish "turf." By breaking up these groups, the police could prevent shootings and drug deals before they happened. It was a "proactive" policing strategy.

But the defense, led by the ACLU, argued that the law was dangerously vague. They argued it violated the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. Basically, a law is unconstitutional if it's so vague that an average person can't tell what's legal and what's not.

Why the Supreme Court Ruled Against Chicago

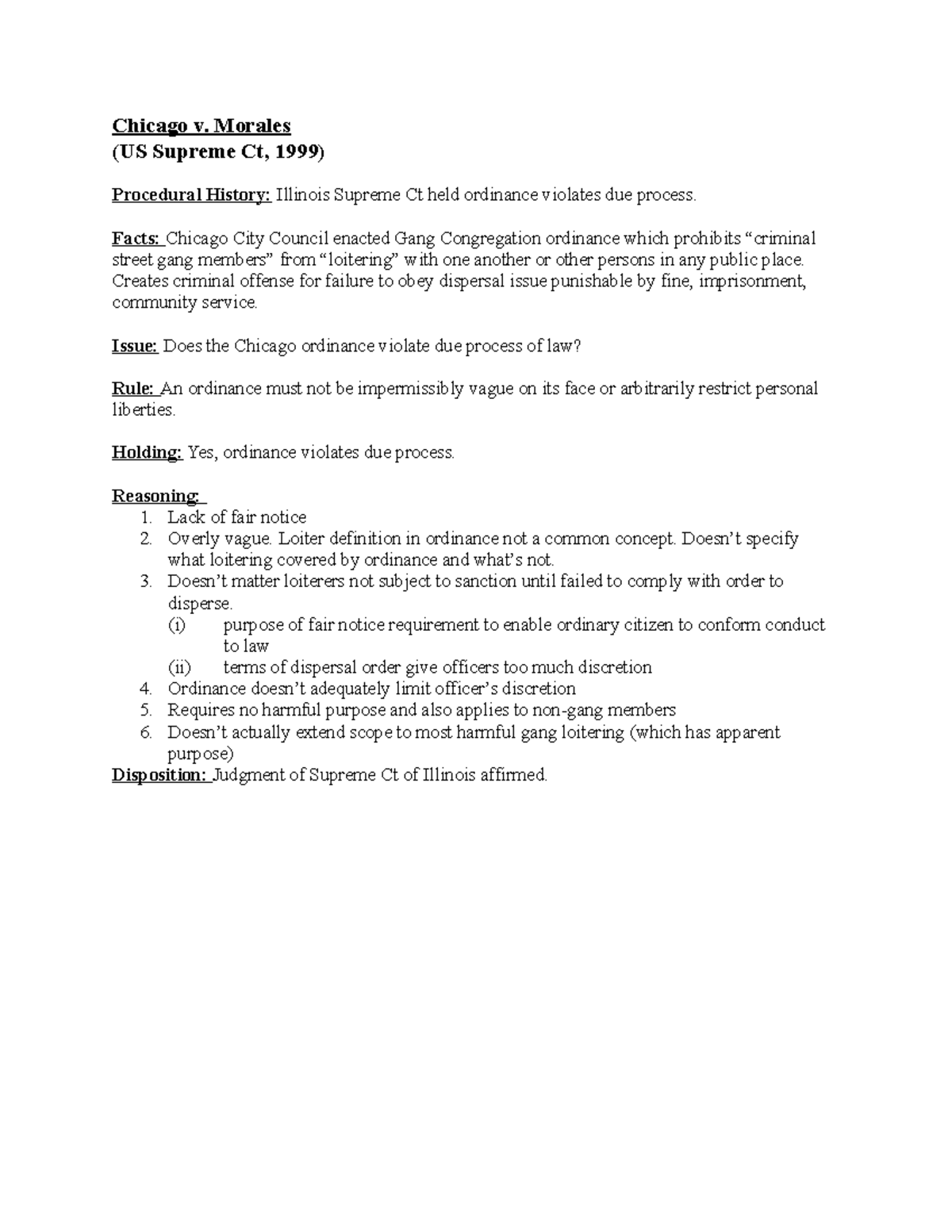

In 1999, the Supreme Court issued its 6-3 decision. Justice John Paul Stevens wrote the plurality opinion, and he didn't pull any punches. The Court found that the ordinance was "void for vagueness" for two main reasons.

💡 You might also like: Sweden School Shooting 2025: What Really Happened at Campus Risbergska

First, it failed to provide fair notice to citizens. If "loitering" just means "no apparent purpose," how is anyone supposed to know when they are breaking the law? One person’s "hanging out" is another person’s "loitering." The law didn't distinguish between innocent behavior and criminal intent.

Second, and perhaps more importantly, the law gave way too much discretion to the police. It basically turned every cop into a legislator who could decide on the spot what was a crime. Justice Stevens famously noted that the ordinance reached a "substantial amount of innocent conduct." He pointed out that even someone waiting for a bus or talking to a friend could be caught in the dragnet.

The Dissenting Voices

It wasn't a unanimous decision. Justice Antonin Scalia wrote a fiery dissent. He argued that the "right to loiter" wasn't a fundamental liberty protected by the Constitution. To Scalia, the city had a legitimate interest in maintaining order and protecting its citizens from gang intimidation. He felt the Court was overstepping by striking down a law that the people of Chicago clearly wanted.

Justice Clarence Thomas also dissented, focusing on the impact of gang activity on poor neighborhoods. He argued that the "vague" law was a small price to pay for the safety it provided to law-abiding citizens who were prisoners in their own homes because of gang violence.

📖 Related: Will Palestine Ever Be Free: What Most People Get Wrong

The Lasting Impact of Morales

Even though Chicago lost the case, the story didn't end there. The city actually went back and drafted a new ordinance. This time, they were much more specific. The new version required police to have "probable cause" that the group was actually engaging in gang activity, and it defined loitering more narrowly.

City of Chicago v. Morales remains a landmark case because it sets the boundary for "broken windows" policing. It tells cities that while they can fight crime, they can't do it by sacrificing the basic civil liberties of everyone on the street. You can't just arrest your way out of a gang problem by making "standing around" a crime.

What Most People Get Wrong

A lot of people think this case was a win for gangs. It wasn't. It was a win for anyone who wants to walk down the street without being harassed by the state. If the Morales ruling had gone the other way, police departments across the country would have had a green light to clear any street corner of "undesirables" at any time.

Today, we see the echoes of Morales in debates over "stop and frisk" and other proactive policing tactics. The core question remains: how do we balance public safety with individual freedom?

Actionable Insights and Next Steps

If you are interested in how local laws affect your rights, or if you live in an area with active "loitering" or "vagrancy" laws, here is what you should do:

- Read your local ordinances. Most city codes are available online. Search for keywords like "loitering," "curfew," or "obstruction" to see how your city defines these "crimes."

- Understand the "Void for Vagueness" doctrine. This isn't just a legal curiosity; it's a shield. If a law doesn't clearly define what is prohibited, it may be unchallengeable in court.

- Monitor local police oversight boards. Laws are only as good as the people enforcing them. Stay informed about how your local department uses discretionary stops.

- Support legal aid organizations. Groups like the ACLU or local public defender offices are the ones who take these cases to the Supreme Court. They rely on public support to protect these fundamental rights.

- Check the status of "Gang Injunctions" in your state. Some cities have moved away from broad loitering laws and instead use civil injunctions against specific gang members. These are also legally controversial and frequently challenged.

The legacy of City of Chicago v. Morales is a reminder that in a free society, "having no apparent purpose" isn't a crime. It's a right.