Ever looked at a map and wondered why on earth there are two dozen different Springfields? Or why a tiny town in the middle of New Mexico is named after a 1950s game show?

Honestly, the way we landed on city names United States is a mess. It's a weird, beautiful, sometimes lazy, and often accidental patchwork of history. It isn't just about honoring the "founding fathers" or looking back at Europe. It's about coin flips, drunken bets, and people simply wanting to feel a little less lonely in a new place.

📖 Related: List of all big cats: What Most People Get Wrong

The Lazy Habit of Copy-Pasting Europe

Early settlers weren't exactly creative. If you’re a homesick colonist from England, you don't brainstorm a new name; you just slap "New" in front of your hometown and call it a day.

That’s how we got New York and New London. But sometimes they didn't even bother with the "New." Take Boston, Massachusetts. It’s named after Boston, Lincolnshire. Most people think of the American version as the "real" one now, but it’s basically just a high-budget sequel.

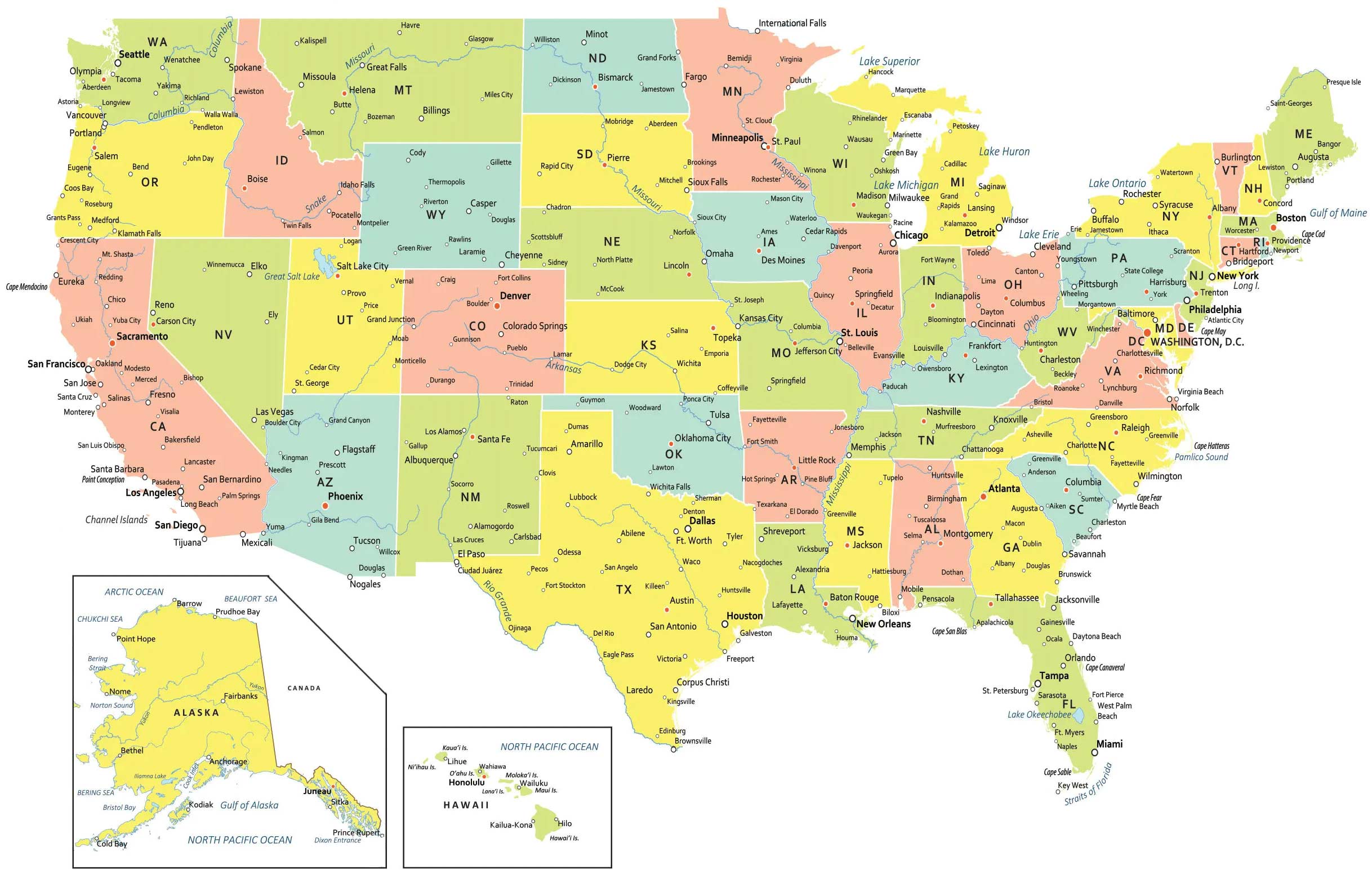

It wasn't just the British doing this. The Dutch gave us New Amsterdam (now New York). The French left their fingerprints all over the map too. Think of St. Louis or New Orleans. Then you’ve got the Spanish in the South and West—San Francisco, Los Angeles, Santa Fe.

The St. Petersburg Coin Toss

One of my favorite stories is how St. Petersburg, Florida, got its name. It came down to a literal coin toss. John C. Williams (from Detroit) and Peter Demens (from Russia) couldn't agree. Demens won the toss and named it after his birthplace in Russia.

Williams? He lost. He got to name the first hotel instead. He called it the Detroit Hotel. Fair trade, I guess.

City Names United States: The Indigenous Roots We Forget

A huge chunk of the names we use every day aren't European at all. They’re distorted versions of Native American words.

Take Chicago. It’s a cool, powerful name, right? Well, it comes from the Miami-Illinois word shikaakwa.

What does that mean? Basically, "wild garlic" or "stinky onion."

The area was literally a swamp full of smelly wild leeks. It’s funny because we treat these names with such reverence now, but to the people who first lived there, it was just a literal description of the land.

- Milwaukee: Likely from an Algonquian word meaning "good land" or "pleasant place."

- Seattle: Named after Chief Si'ahl.

- Tallahassee: A Muskogean word for "old town" or "abandoned fields."

- Topeka: This one is the best. In the Kansa language, it roughly means "a good place to dig potatoes."

We often think these names are "mystical," but they were usually just practical directions. "Go to the place where the potatoes are good." It makes sense.

The Most Common Name is a Battle

If you had to guess the most common city name in the U.S., you’d probably say Washington. It's a good guess. George Washington is everywhere. But it’s actually a tie or a close second depending on how you count "places" versus "incorporated cities."

For a long time, Franklin held the crown.

👉 See also: Why the Cordillera Central Puerto Rico is Actually the Heart of the Island

Benjamin Franklin was the celebrity of his era. People loved him. There are around 30 distinct Franklins across the country. Clinton and Madison are right up there too.

Then you have the "villes" and the "burgs."

After the American Revolution, everyone was so pro-French that "-ville" became the trendiest suffix you could use. Louisville was named to honor King Louis XVI for helping out in the war. On the flip side, "-burg" is Germanic and English, and "-town" or "-ton" (like Charleston) was the old-school British way of doing things.

When Pop Culture Takes Over

Sometimes, a name change is just a PR stunt.

Take Truth or Consequences, New Mexico. Before 1950, it was just Hot Springs. Then, Ralph Edwards, the host of the popular radio show Truth or Consequences, announced he’d broadcast the 10th-anniversary show from the first town that renamed itself after the program.

Hot Springs said, "Why not?" and changed it officially. They never changed it back.

🔗 Read more: Grand Hotel Atlantis Bay Taormina: Is the Mermaid Life Actually Worth the Price?

Then there’s Santa Claus, Indiana. They originally wanted to call themselves Santa Fe, but the post office told them there was already a Santa Fe in Indiana. It was Christmas Eve, kids were around, and someone suggested Santa Claus. Now, they get hundreds of thousands of letters addressed to Saint Nick every year.

The Weirdest Ones on the Map

We have to talk about the ones that make no sense.

- Zzyzx, California: A guy named Curtis Howe Springer made it up because he wanted it to be the "last word" in the English language.

- Monkey’s Eyebrow, Kentucky: Nobody actually knows for sure, but the local legend is that if you look at the map of the county, it looks like a monkey’s head, and the town is right where the eyebrow would be.

- No Name, Colorado: Literally the result of a paperwork error where "No Name" was written in a blank space and it just stuck.

Why This Actually Matters

Understanding the origin of city names United States helps you see the layers of migration and conflict that built the country. You can see where the Germans settled by looking for the "Hamels" and "Berlins." You can see the path of the pioneers by how many "Portlands" and "Springfields" they dragged across the mountains with them.

It's a map of our ego, our nostalgia, and our sense of humor.

Actionable Insights for Your Next Trip

Next time you're driving through a town with a weird name, don't just laugh at the sign.

- Check the Local Library: Most small towns have a "local history" shelf. The story of the name is almost always the first chapter.

- Look at the Suffixes: If it ends in -burg, look for German or Scottish roots. If it's -ville, look for post-Revolutionary French influence.

- Search the Etymology: Use a site like the Online Etymology Dictionary or local historical society pages. You’ll find that "stinky onions" or "good potatoes" tell you more about the soul of a place than a statue ever could.

The U.S. map isn't a finished document. It's a conversation that's been going on for four hundred years, and it's still being written, one coin toss at a time.