You’ll hear it before you see it. It isn't the sound of angelic choirs or silent prayer. Honestly, it’s usually the sound of a Greek Orthodox monk shouting at a group of tourists to move faster, or the frantic clicking of cameras against a backdrop of ancient, soot-stained stones. Jerusalem is loud. But the Church of the Holy Sepulchre is a different kind of loud. It is a chaotic, beautiful, slightly confusing mess of history that doesn't care if you're ready for it.

Most people expect a pristine cathedral. They want high vaulted ceilings and a sense of quiet reverence like you'd find at St. Peter's in Rome. Instead, they walk into a sprawling, dimly lit complex that smells like a mix of beeswax and a thousand years of damp stone. It’s crowded. It’s dark. It’s arguably the most important building in Christendom, and yet it feels remarkably human.

The site supposedly houses the two holiest spots in Christianity: the site where Jesus was crucified (Golgotha) and the empty tomb where he was buried and resurrected. Whether you’re a believer or a history nerd, the sheer weight of what’s happened within these walls is enough to make your head spin. But there's a lot of misinformation floating around about how the place actually works.

The Status Quo: Why Nobody Can Move a Ladder

If you look up at the window ledge above the main entrance, you’ll see a small wooden ladder. It’s been there since the mid-1800s. No, the construction crew didn't just forget it. It stays there because of something called the Status Quo.

Back in 1757, and later reinforced in 1852, the Ottoman Empire got tired of the different Christian denominations—the Greeks, Catholics, Armenians, Copts, Syrians, and Ethiopians—fighting over who owned which inch of the church. They issued a decree: everything stays exactly as it is. Forever. If a nail was in a wall in 1852, it stays there. If a monk wants to move a chair two inches to the left, he might trigger a diplomatic incident or a physical brawl.

This isn't an exaggeration. In 2002, an Egyptian Coptic monk moved his chair into the shade of an Ethiopian area on the roof. It ended in a fight that sent eleven people to the hospital. It sounds ridiculous, but it’s the only way the Church of the Holy Sepulchre functions. The division of space is measured down to the millimeter.

🔗 Read more: Why Presidio La Bahia Goliad Is The Most Intense History Trip In Texas

The keys to the church? They aren't held by any of the Christians. Since the 12th century, the Joudeh and Nuseibeh families—who are Muslim—have been the official door-keepers and key-holders. Every morning, a member of the family brings the key, and a monk from one of the denominations opens the door. It’s a checks-and-balances system that has survived crusades, empires, and modern wars.

Finding the Actual Tomb

Once you pass the Stone of Unction—where many pilgrims kneel to rub oil and cloths on the slab where Jesus’ body was allegedly prepared for burial—you hit the Rotunda. This is the heart of the building. Under a massive dome lies the Aedicuna, a small chapel-within-a-church that houses the Holy Sepulchre itself.

Is it the real tomb?

Archaeologically speaking, it’s complicated. For centuries, skeptics pointed out that the church is located inside the current walls of the Old City, while Jewish law at the time required burials to be outside the city. However, excavations have shown that in the first century, this area was actually a quarry located outside the walls.

In 2016, National Geographic followed a team from the National Technical University of Athens as they restored the Edicule. For the first time in centuries, they lifted the marble slab covering the burial bed. What they found underneath was a secondary marble slab with a cross carved into it, dating back to the Crusader era, and beneath that, the original limestone bedrock of the cave. The mortar they tested dated back to the 4th century, the era of Constantine the Great. This doesn't "prove" Jesus was there, but it proves the site has been recognized as the tomb for at least 1,700 years.

💡 You might also like: London to Canterbury Train: What Most People Get Wrong About the Trip

Why the "Garden Tomb" confuses people

You’ll often hear Protestant groups talk about the Garden Tomb, located a short walk north of the Damascus Gate. It looks much more like what people imagine: a quiet garden, a rock-cut tomb, a peaceful atmosphere. It’s lovely. But almost all serious archaeologists, including those who are devout Christians, agree that the Garden Tomb is likely an Iron Age tomb (9th–7th century BC) that was reused. It doesn’t fit the New Testament description of a "new tomb." The Church of the Holy Sepulchre, despite its noise and grime, has the much stronger historical claim.

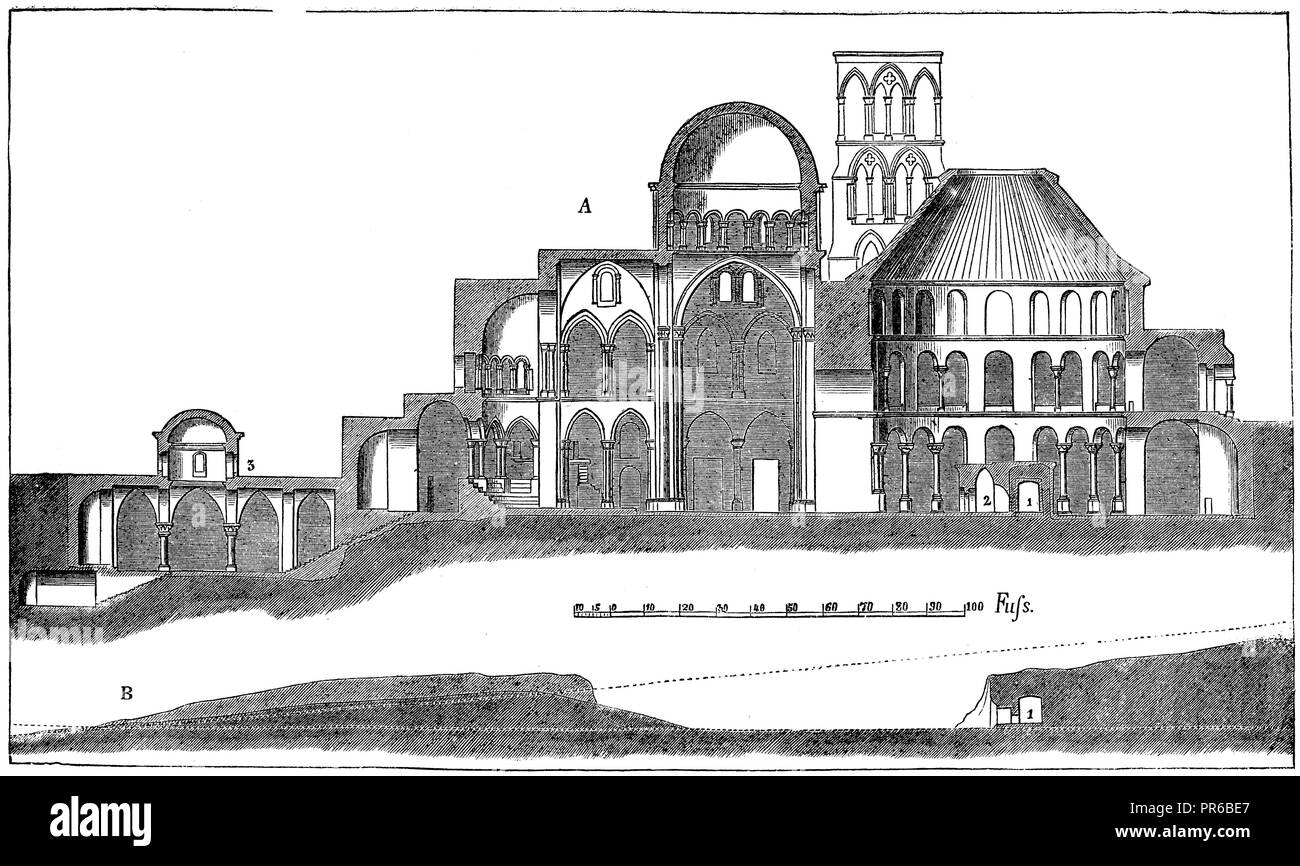

Navigating the Different Levels

The church is basically a 3D puzzle. You have to climb steep, slippery stone stairs to get to Calvary (Golgotha). Up there, you’ll find two chapels: one Catholic and one Greek Orthodox. People crawl under an altar to touch a piece of rock encased in glass, believed to be the spot where the cross stood.

Then you go down.

Way down.

Beneath the main floor is the Chapel of Saint Helena and, further down, the Chapel of the Finding of the Cross. This is a damp, cavernous space where tradition says Empress Helena discovered the "True Cross" in a discarded cistern. The walls here are covered in thousands of small crosses carved by medieval pilgrims. It’s one of the quietest spots in the building, mostly because the tour groups hate the stairs.

📖 Related: Things to do in Hanover PA: Why This Snack Capital is More Than Just Pretzels

The Coptic and Ethiopian corners

Don't miss the back. If you walk around the rear of the Edicule, there’s a tiny, cramped Coptic chapel. It’s basically a closet, but it lets you touch the backside of the tomb rock.

Even further "out," if you head to the roof via a side staircase near the entrance, you’ll find Deir es-Sultan. This is an Ethiopian Orthodox monastery that looks like a tiny African village perched on top of a Crusader church. It’s sun-bleached, quiet, and smells of different incense. The Ethiopian monks have been in a legal battle with the Copts over this specific patch of roof for generations. Again, the Status Quo is a heavy burden.

The Holy Fire: A Jerusalem Mystery

Every year, on the Saturday before Orthodox Easter, thousands of people cram into the church for the Ceremony of the Holy Fire. The Greek Patriarch enters the tomb, which has been inspected for matches or lighters. After a period of prayer, a "blue light" is said to emit from the tomb, lighting his lamp.

He emerges, and the fire is passed from person to person until the entire church is glowing with thousands of candles. Believers claim the fire doesn't burn their skin or hair for the first few minutes. Skeptics claim it’s white phosphorus or a simple trick. Regardless of what you believe, the energy in the building during this event is borderline terrifying. It’s hot, crowded, and visceral. It is the furthest thing from a "tourist attraction" you can imagine.

Survival Tips for the Modern Visitor

If you're actually planning to visit, don't just show up at 10:00 AM. You’ll be miserable. The lines to enter the tomb can be three hours long.

- Go at 5:00 AM. The doors open early. The air is cool, the light is dim, and the only people there are the monks chanting their morning liturgies. It’s the only time the building feels truly spiritual rather than just historical.

- Watch your head and feet. The floors are uneven and polished to a mirror shine by millions of feet. People slip constantly.

- Dress the part. They will kick you out for shorts or bare shoulders. This isn't a museum; it's a functioning place of worship for some of the most conservative religious groups on earth.

- The "Secret" Exit. Sometimes the main door gets jammed with a massive tour group from a cruise ship. Look for the small door that leads through the Coptic passage to the rooftop—it’s a great way to escape the crush.

The Church of the Holy Sepulchre isn't "pretty" in the traditional sense. It’s a scarred, patched-together fortress of faith. It has survived fires, earthquakes, and countless sieges. It’s a place where the divine meets the deeply human—including all our petty arguments and territorial disputes. That’s probably why it feels so authentic. It’s not a sanitized version of history; it’s the real thing.

Actionable Insights for Your Visit

- Check the Liturgy Schedule: The various denominations have strict times for their services. If you arrive during a major Greek Orthodox procession, certain areas will be roped off. Check the Franciscan "Christian Information Centre" website before you go.

- Look for the "Graffiti": In the staircase leading down to the Chapel of Saint Helena, look closely at the walls. These crosses were carved by Crusaders and pilgrims from the 1100s. It’s a direct physical link to the medieval world.

- Explore the Roof: Most people miss the Ethiopian monastery (Deir es-Sultan). To find it, go to the right of the main entrance, find the stairs, or go through the Church of St. Alexander Nevsky nearby.

- Stay Nearby: If you stay at a guesthouse inside the Christian Quarter, you can visit the church late at night (it usually closes around 7:00 or 8:00 PM depending on the season). The atmosphere changes completely once the day-trippers leave.

- Touch the Bedrock: Don't just look at the gold and marble. In the Syrian Orthodox chapel (which is in a state of disrepair), you can see actual first-century "kokhim" tombs. This is the best visual proof that the area was indeed a cemetery in the time of Jesus.