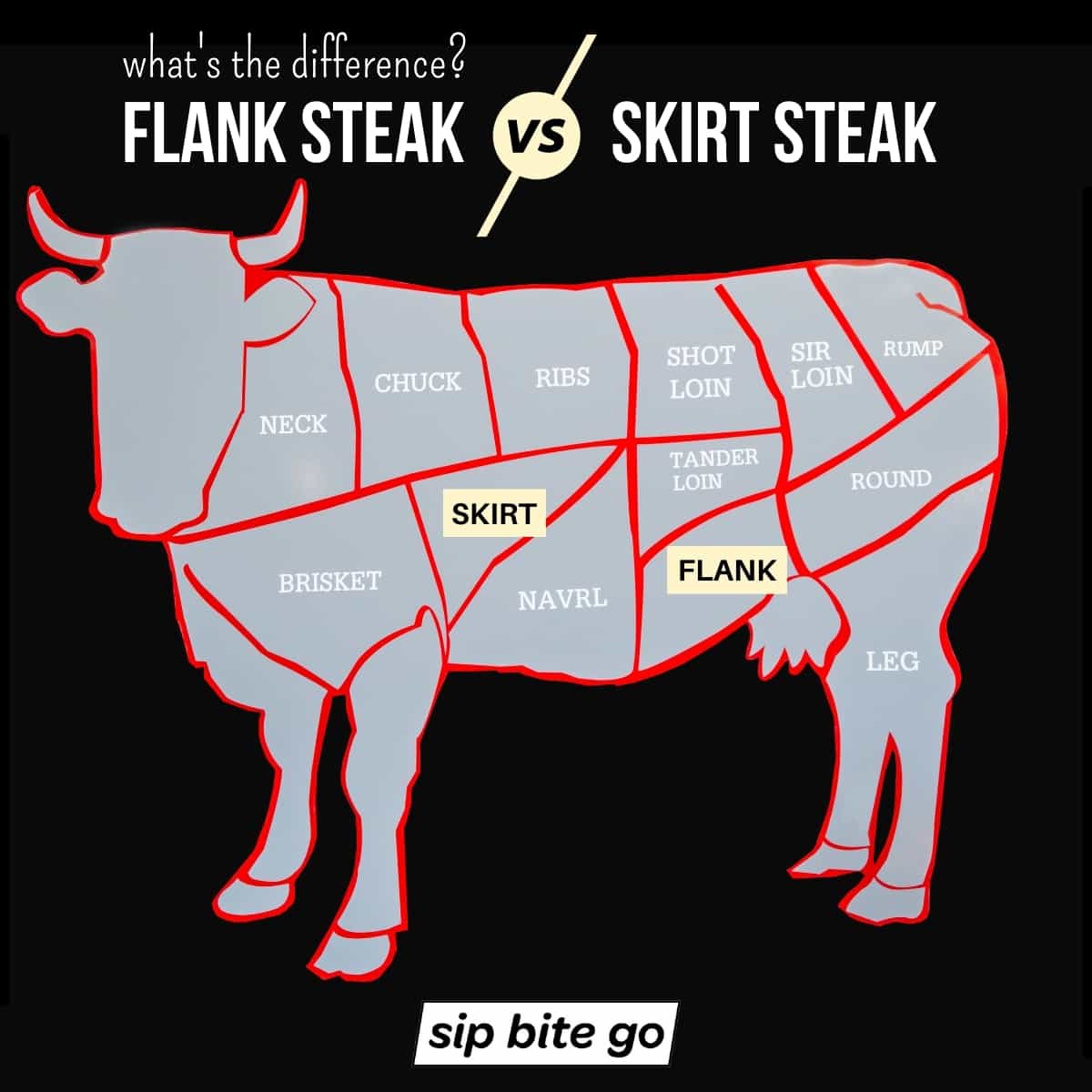

You’re standing in the meat aisle at the grocery store, staring at three long, flat slabs of beef that look almost identical. One is labeled chuck, one says skirt, and the third is flank. They all look like they’d be great for tacos or stir-fry, right? Honestly, if you grab the wrong one for the wrong cooking method, you’re basically signing up to chew on a rubber band for twenty minutes. It’s frustrating. It's expensive. And if you’ve been following the classic chuck skirt flank NYT cooking trends, you know the New York Times Food section has spent decades trying to teach us the nuance between these "tough" cuts.

They aren't actually tough. They’re just misunderstood.

Most people think "steak" means a ribeye or a filet mignon—the stuff that melts if you look at it funny. But the real flavor lives in the muscles that actually do work. We’re talking about the diaphragm, the abdominal walls, and the lower shoulder. These cuts are fibrous. They have grain. If you respect that grain, you get a meal that tastes like actual beef, not just butter and salt. If you don't? Well, you might as well eat your shoe.

The Identity Crisis of the Skirt Steak

The skirt steak is the darling of the chuck skirt flank NYT recipe archives, particularly when you look at the work of legendary food writers like Melissa Clark or Mark Bittman. But here is the thing: there are actually two different skirt steaks.

The outside skirt is the holy grail. It’s the transversus abdominis muscle. It’s thick, it’s marbled, and it’s usually sold to high-end restaurants and steakhouses. If you find it at a butcher, buy it immediately. Don't even think about it. The inside skirt, which is what you’ll find in 90% of supermarkets, is thinner and has a lot more silver skin. It shrinks like crazy when it hits the pan.

If you’re trying to replicate a classic NYT Cooking fajita recipe, you need high heat. Skirt steak loves a screaming hot cast-iron skillet. Because it’s so thin, you want to char the outside to a deep, mahogany crust while keeping the inside a perfect medium-rare. If you cook a skirt steak to well-done, you’ve essentially created a leather belt. It’s done. Over. Move on.

The grain is the most important part here. Look at the meat. You’ll see long fibers running across the width. When you carve it, you must cut against those fibers. You’re essentially doing the work your teeth can’t do by shortening those muscle strands. It makes the difference between "this is delicious" and "I need a dentist."

🔗 Read more: Finding the Right Look: What People Get Wrong About Red Carpet Boutique Formal Wear

Why Flank Steak is the Reliable Middle Child

Flank steak is a different beast entirely. It comes from the cow’s lower belly. It’s much leaner than skirt and has a very distinct, tight grain. Think of it like a dense piece of wood. It’s great for marinating because it’s relatively porous, but it doesn't have the internal fat (marbling) that skirt does.

Whenever the chuck skirt flank NYT debate comes up in home kitchens, flank usually wins for presentation. It’s a wide, flat rectangle that looks beautiful when sliced on a bias. J. Kenji López-Alt, who has written extensively for various high-profile publications including the Times, often points out that flank steak is the most sensitive to overcooking.

You cannot treat flank like a ribeye. You can’t just "wing it."

Because it’s so lean, it dries out the second it passes 145 degrees Fahrenheit. You want to pull it off the heat at about 130 or 135 degrees. Let it rest! If you cut into a flank steak the moment it leaves the grill, all the juice—which is the only thing providing moisture in such a lean cut—will dump out onto your cutting board. You’ll be left with a grey, dry slab of sadness. Give it ten minutes. The fibers will relax, the juices will redistribute, and you’ll actually enjoy your dinner.

The Chuck Conundrum: It's Not Just for Pot Roast

Now, let’s talk about the "chuck" part of the chuck skirt flank NYT trio. This is where people get really confused. "Chuck" is a massive primal cut from the shoulder. Usually, we think of it as pot roast—low and slow, braised in red wine for four hours until it falls apart.

But there are "steaks" hidden inside the chuck.

💡 You might also like: Finding the Perfect Color Door for Yellow House Styles That Actually Work

- The Flat Iron: This is actually the second most tender muscle in the entire cow. It’s cut from the top blade. It’s juicy, it’s well-marbled, and it’s significantly cheaper than a New York Strip.

- The Chuck Eye: Often called the "Poor Man’s Ribeye." It’s the two inches of meat that sit right next to the ribeye primal. It tastes almost identical but costs about half as much.

- The Denver Steak: A relatively "new" cut discovered by meat scientists (yes, that’s a real job) in the 2000s. It’s intensely beefy and great for quick searing.

The problem with chuck is that it's inconsistent. One inch to the left and you’ve got a tender steak; one inch to the right and you’ve got a piece of gristle that requires a slow cooker. This is why the NYT often suggests "Chuck" for stews or burgers. If you’re grinding your own beef for burgers—which you absolutely should do—chuck is the gold standard. It has the perfect 80/20 meat-to-fat ratio that makes a burger crave-able.

The Science of the Marinade: Does It Actually Work?

We’ve all seen the recipes that tell you to marinate your flank steak in soy sauce, ginger, and lime for 24 hours. Here’s a little secret that many "expert" columns won't tell you: marinating doesn't really tenderize the middle of the meat.

Salt penetrates. Acid (like lime juice or vinegar) can actually "cook" the surface of the meat, turning it mushy if left too long. The flavor molecules in garlic or rosemary are often too large to travel deep into the muscle fibers.

So why do we do it? For the surface.

When you grill a marinated chuck skirt flank NYT style steak, the sugars in the marinade caramelize. This is the Maillard reaction. It creates that crust that makes your brain go "Yes, this is food." If you want to actually tenderize these cuts, you’re better off using mechanical tenderization (a jaccard or a mallet) or, better yet, just slicing it correctly at the end.

Real World Application: Choosing Your Fighter

Imagine you’re making stir-fry. You want meat that cooks in ninety seconds. Go for the skirt. It’s thin, it has a high surface-area-to-volume ratio, and it loves the high heat of a wok.

📖 Related: Finding Real Counts Kustoms Cars for Sale Without Getting Scammed

Are you making a London Broil or a big steak salad for a dinner party? Flank is your winner. It’s easy to slice into uniform, elegant strips. It’s the "civilized" version of these rugged cuts.

Building the perfect smash burger or a hearty beef bourguignon? Stick with chuck. The connective tissue (collagen) in chuck breaks down into gelatin when cooked slowly, which gives stews that silky, rich mouthfeel that you just can't get from leaner cuts.

A Few Things People Get Wrong

People often swap these interchangeably, but they shouldn't. You can't really "sear" a chuck roast like a flank steak and expect to eat it. It’ll be like chewing on a tire. Similarly, if you put a flank steak in a slow cooker for eight hours, it won't become tender; it will become "stringy." It’ll turn into beef-flavored dental floss.

Also, watch out for the "Bistro Steak" or "Teres Major." It's another chuck-adjacent cut that is becoming popular in trendy restaurants. It’s shaped like a tiny tenderloin and is incredibly soft. If you see it, grab it. It’s the industry’s best-kept secret.

Summary of Actionable Steps

Stop buying pre-sliced "stir-fry meat." It’s usually the scraps they couldn't sell as steaks, and it’s often a mix of different muscles that cook at different rates. Buy the whole muscle and do the work yourself. It takes three minutes.

- Identify the Grain: Before you even salt the meat, look at which way the lines are running. Memorize it. Once the steak is charred, it’s harder to see.

- The 45-Degree Rule: When slicing flank or skirt, hold your knife at a 45-degree angle. This creates more surface area in each slice and further breaks down those tough fibers.

- Salt Early: If you have time, salt your meat 40 minutes before cooking. The salt draws out moisture, dissolves into a brine, and then gets reabsorbed, seasoning the meat deeply and helping the proteins retain juice.

- The Poke Test is a Lie: Don't rely on "poking" the meat to see if it’s done. Use a digital thermometer. For these cuts, the window between "perfect" and "ruined" is about five degrees.

- Clean the Silver Skin: If your butcher was lazy, you might see a white, shiny membrane on your skirt steak. Peel it off. It doesn't melt, it doesn't taste good, and it’ll make the meat curl up in the pan.

If you follow these steps, you’ll stop wasting money on "okay" meals and start producing restaurant-quality steak at home. These cuts are the backbone of great home cooking because they offer the best flavor-to-price ratio in the entire cow. Just remember: heat it fast, let it rest, and always, always cut against the grain.