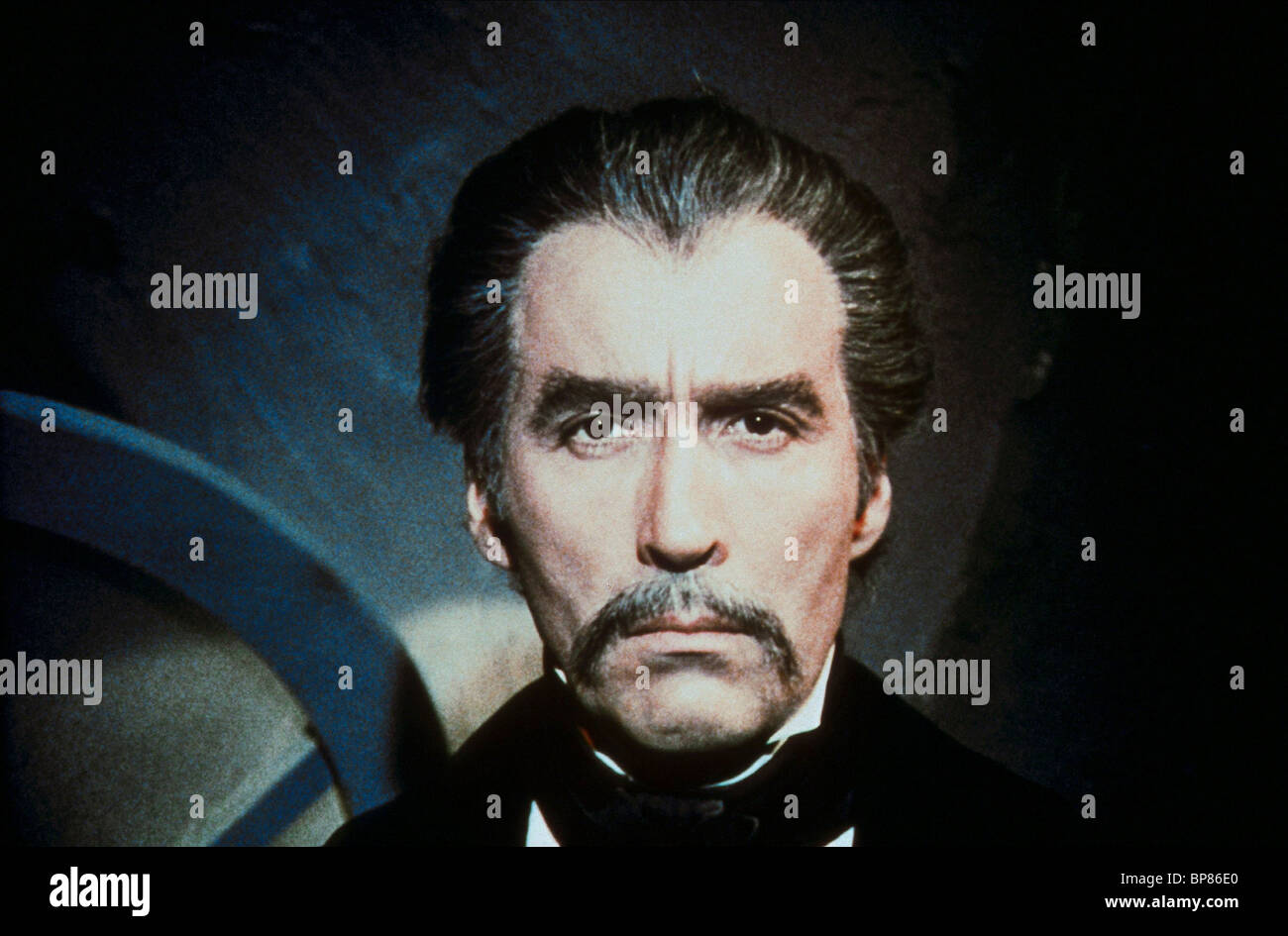

Christopher Lee hated his own movies. Well, maybe "hated" is a strong word, but by the time he was filming Christopher Lee Count Dracula 1970 projects, he was visibly annoyed. He felt like a prisoner. He’d become the face of Hammer Film Productions, but he constantly complained that they weren't actually following Bram Stoker’s book. He wanted the mustache. He wanted the gray hair. He wanted the dignity of the original source material rather than just being a red-eyed monster lurking in the shadows of a castle.

1970 was a weirdly pivotal year for Lee. It was a crossroads.

While most fans think of the Hammer "formula" when they picture Lee, 1970 gave us two very different versions of the Count. One was Taste the Blood of Dracula, a Hammer production where he barely spoke and looked like he wanted to be anywhere else. The other was Count Dracula, directed by the legendary Spanish cult filmmaker Jesús "Jess" Franco. This second one is the one film buffs argue about late at night. It was supposed to be the "faithful" one. It promised to give us the Christopher Lee Count Dracula 1970 performance he’d been begging for since 1958.

Did it work? Honestly, it's complicated.

The Hammer Problem vs. the Franco Experiment

By 1970, Hammer Films was in a bit of a rut. They knew Lee was their biggest draw, but they also knew they didn't need to give him much dialogue to sell tickets. In Taste the Blood of Dracula, he's basically a force of nature. He's an avenging shadow. He’s terrifying, sure, but Lee felt it was beneath him. He was a classically trained actor who spoke multiple languages and had a deep, resonant voice that deserved more than just hissing at a crucifix.

Enter Jess Franco.

Franco approached Lee with a pitch that was hard to refuse: a low-budget, independent production that would follow Stoker’s novel beat-for-beat. For the first time, Lee would play the Count as an older man who grows younger as he feeds. He got the mustache. He got to deliver lines straight from the 1897 text.

✨ Don't miss: The Lil Wayne Tracklist for Tha Carter 3: What Most People Get Wrong

But here's the kicker. The movie had no money.

If you watch the Franco film today, you'll see Lee giving an incredible, nuanced performance while everything around him is... well, it's a mess. The bat on a string is visible. The lighting is inconsistent. The "wolf" looks suspiciously like a very bored German Shepherd. It's a tragedy of cinema history that Lee’s most accurate portrayal of the character is trapped inside one of his most poorly produced films.

Why the Christopher Lee Count Dracula 1970 Look Changed Everything

Think about the silhouette. Before 1970, the cinematic Dracula was mostly Bela Lugosi—widow's peak, heavy cape, thick Hungarian accent. Or he was the early Hammer Dracula—feral, bloodshot eyes, aggressive.

The Christopher Lee Count Dracula 1970 iteration in the Jess Franco film introduced the "Gentleman Count" to a wider audience. This version was sophisticated. He was a nobleman first and a predator second. Lee played him with a chilling, cold intellect. He wasn't just a monster; he was a host. This version influenced how we see vampires even today, shifting the focus from "beast" to "aristocrat."

Actually, Lee’s performance in that 1970 Franco film is probably the closest we ever got to the literary Dracula until Gary Oldman stepped into the role in 1992.

Lee’s frustration with the role is legendary. He often told interviewers that he only kept doing the Hammer sequels because the studio heads literally told him that if he didn't do it, they couldn't pay the crew. They guilt-tripped him into the cape. "Think of all the people you'll be putting out of work, Christopher!" they’d say. So he'd sigh, put the fangs back in, and collect his paycheck. But 1970 was the year he tried to break the mold.

🔗 Read more: Songs by Tyler Childers: What Most People Get Wrong

The Secret Appearance in Scars of Dracula

Technically, 1970 also gave us Scars of Dracula. This is often cited as the point where the Hammer series started to get "juicy." It’s much bloodier than the earlier films. It’s got that vibrant, Technicolor-red blood that looks like paint.

In Scars, Lee actually gets a bit more to do than in Taste the Blood. He’s cruel. He’s sadistic. He’s not just biting people; he’s actively tormenting his victims. It’s a meaner movie. For many horror purists, this is the definitive Christopher Lee Count Dracula 1970 experience because it combines the high production values of Hammer with a slightly more verbal Lee.

It’s fascinating to watch these films side-by-side.

- Taste the Blood of Dracula: Lee as a silent icon.

- Count Dracula (Franco): Lee as a literary scholar.

- Scars of Dracula: Lee as a brutal slasher-villain.

Three movies. One actor. One year. The range is wild when you actually sit down and analyze it.

Acknowledging the Flaws

We have to be real here. The Jess Franco film is hard to watch if you aren't a hardcore fan. The "zoom" lens was Franco's favorite toy, and he uses it every three seconds. It’s dizzying. It’s also quite slow. While Lee is mesmerizing, the rest of the cast—including Herbert Lom as Van Helsing—often feels like they’re in different movies.

Also, the claim that it's "100% faithful to the book" is a bit of a marketing stretch. It hits the big milestones, but it still skips the London sections of the novel almost entirely due to budget constraints. They filmed in Spain and pretended it was Transylvania (and England), and it sort of works if you squint.

💡 You might also like: Questions From Black Card Revoked: The Culture Test That Might Just Get You Roasted

How to Appreciate This Era of Horror Today

If you want to understand the Christopher Lee Count Dracula 1970 legacy, don't just watch a "best of" clip on YouTube. You need the context. You need to see the struggle of an actor who felt he was too good for the material he was being forced to perform. That tension—that aristocratic disdain Lee brings to the screen—is actually perfect for Dracula.

Dracula is a guy who thinks he's better than everyone else. Lee wasn't acting that part; he was feeling it.

Actionable Insights for Fans and Collectors

To truly dive into this specific era, follow these steps:

- Seek out the "El Conde Dracula" 4K restorations. The old VHS and DVD rips of the Jess Franco film are terrible. The lighting is so muddy you can't see Lee's expressions. Modern restorations actually let you see the subtle graying in his hair and the detail of his costume, which was his pride and joy.

- Compare the scores. James Bernard’s music for the Hammer films is bombastic and gothic. Bruno Nicolai’s score for the 1970 Franco film is avant-garde and eerie. Listening to them reveals how the tone of the character shifted depending on the studio.

- Read the 1970 interviews. If you can find archives of Famous Monsters of Filmland from that year, Lee is incredibly candid about his desire to move on to roles like Lord Summerisle in The Wicker Man.

- Watch the "Prince of Darkness" documentary. It features Lee talking specifically about the 1970 period and his relationship with Peter Cushing. Their friendship was the polar opposite of their on-screen rivalry.

Lee eventually got his wish. He moved to Hollywood, escaped the "horror" label, and became a legend in Lord of the Rings and Star Wars. But he never truly escaped the Count. Even in his 80s, he could still drop into that terrifyingly still, menacing presence that he perfected in 1970. It was the year he proved he wasn't just a guy in a suit; he was the definitive interpretation of a literary icon.

He didn't need the fangs to be scary. He just needed to stare.

To fully grasp the impact of Christopher Lee’s 1970 output, watch Count Dracula (1970) followed immediately by Scars of Dracula. The contrast in his physical acting—the way he moves his hands, the way he carries his head—reveals a masterclass in character interpretation that most modern horror actors still haven't matched. Investigate the BFI archives for production stills from this year to see the incredible work that went into his makeup, much of which was lost in the poor film processing of the era.