It was Christmas Eve, 1914. Men were dying in the mud. Then, someone started singing. It sounds like a cheap Hollywood script, right? But for director Christian Carion, Joyeux Noël wasn’t about making a "movie." It was about fixing a historical memory that his own country, France, had tried to bury for decades.

Honestly, most war movies are about the bang-bang. They're about who shot whom and which flag stayed flying. Carion didn't care about that. He grew up in Northern France, right near where the trenches used to be, hearing whispers about the "fraternizations." His great-grandfather actually fought in the war. Yet, in French schools, they didn't really talk about the time the soldiers stopped fighting to play soccer and drink champagne. It was considered shameful. A desertion of duty.

When Christian Carion Joyeux Noël finally hit theaters in 2005, it did something weird. It made people realize that the most "heroic" thing those men did wasn't pulling a trigger. It was putting the gun down.

The Battle to Even Make the Film

You’d think a movie about peace would be easy to fund. Wrong. Carion spent years trying to get this off the ground.

The French military archives were famously protective. When he first started digging, he found that the French army had actually tried to erase the records of these truces. They didn't want the world knowing that French, Scottish, and German soldiers had shared cigars. It messed with the narrative of total national hatred.

Carion’s breakthrough came when he found a book by historian Yves Buffetaut called Batailles de Flandres et d'Artois. It documented the specific incidents that eventually formed the backbone of the film.

But even with the facts, the industry was skeptical. A multi-lingual film? In 2005? That was a hard sell. Carion insisted that everyone speak their native tongue—no fake accents. If you were playing a German, you were German. If you were a Scot, you were a Scot. This authenticity is why the movie hasn't aged a day. It feels real because the linguistic barriers on screen were real for the actors too.

What Most People Get Wrong About the 1914 Truce

People think it was just one big party. One afternoon of soccer and then back to work.

💡 You might also like: Kiss My Eyes and Lay Me to Sleep: The Dark Folklore of a Viral Lullaby

The reality Carion portrays—and the history backs this up—is way more complicated and honestly, kinda darker. The "Christmas Truce" wasn't a single event. It happened in pockets all along the Western Front. In some sectors, it lasted an hour. In others, it lasted until New Year's Day.

One of the most heartbreaking details in the film is when the soldiers warn each other about upcoming artillery strikes. "Hey, we're going to shell your trench at 2:00 PM, you should probably move." That actually happened. Once you've seen the photos of a man's kids, it’s remarkably hard to aim a cannon at him.

Carion emphasizes the role of music, specifically the character of Nikolaus Sprink (played by Benno Fürmann). While Sprink is a fictionalized version of real tenors who were sent to the front, the impact was factual. Music was the only bridge they had. When the bagpipes from the Scottish side started responding to the German singing, the war effectively broke. For a moment, the machine stopped.

The Problem with the "Soccer Match"

Everyone talks about the soccer game. It's the most famous part of the Christmas Truce.

In Joyeux Noël, Carion depicts it as a messy, amateur kick-around in the snow. This is actually more accurate than the "official match" myths you see in some documentaries. Most historians, like those at the Imperial War Museum, agree that while there were definitely balls kicked around, there wasn't a formal 90-minute FIFA-style match with scores. It was just guys being guys, trying to remember what it felt like to play instead of kill.

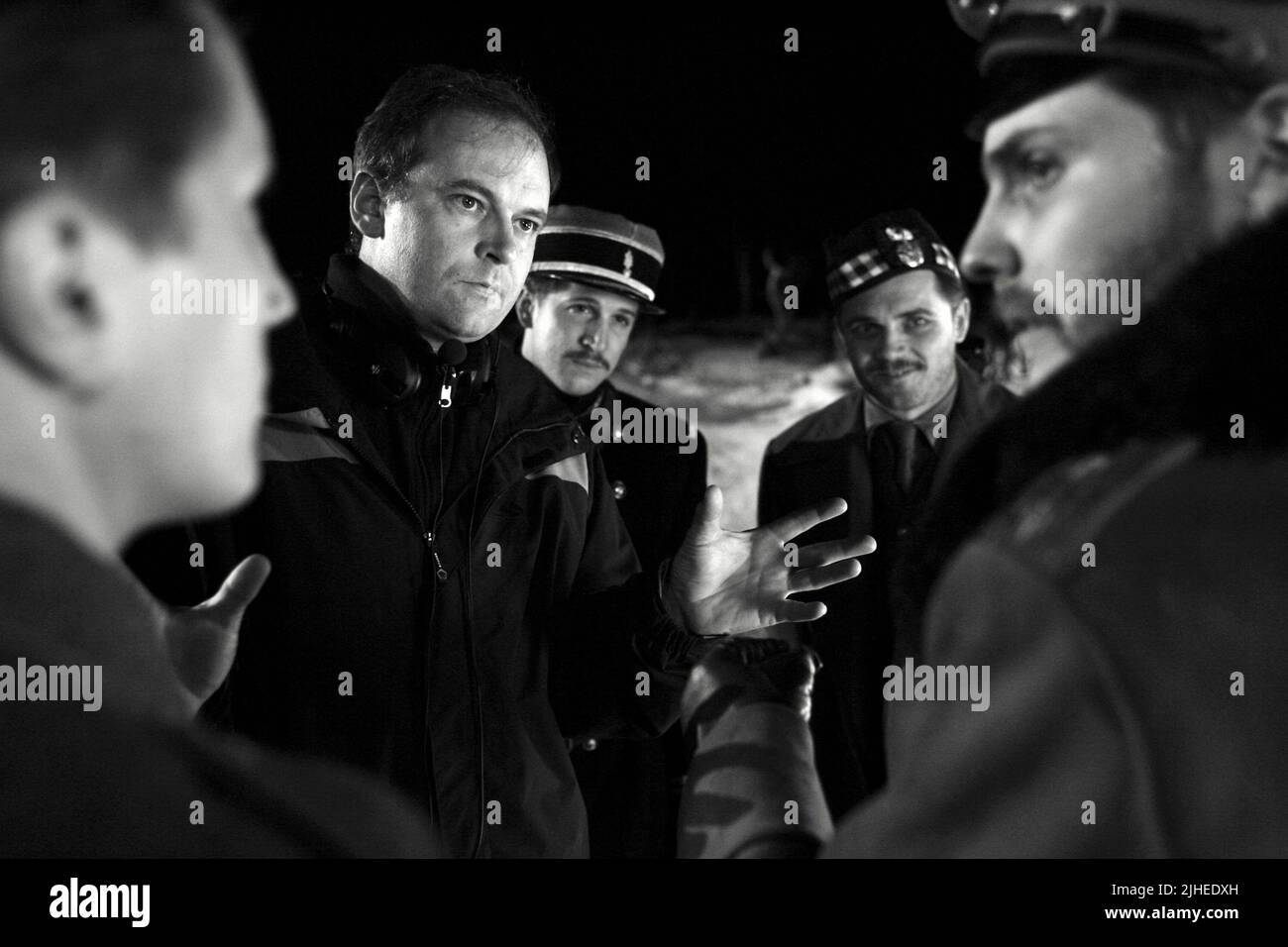

The Casting Genius of Diane Kruger and Guillaume Canet

Carion knew he needed a face for the tragedy.

Diane Kruger plays Anna Sørensen, a Danish soprano. While her presence in the actual trenches is a bit of a "movie" stretch—it’s one of the few places where Carion took some creative liberty for the sake of the narrative—she represents the domestic life the men were missing.

📖 Related: Kate Moss Family Guy: What Most People Get Wrong About That Cutaway

Guillaume Canet, playing Lieutenant Audebert, is the soul of the film. He represents the crushing weight of command. He’s the one who has to face the general (his own father) afterward and explain why he didn't order his men to open fire on "the enemy" while they were burying their dead.

The scene where they bury the bodies is probably the most important in the whole movie. They don't just bury their own. They help each other. They share the shovels. In that moment, the concept of "The Enemy" evaporates. There is only "The Dead."

Why the Ending Still Stings

The most realistic part of Christian Carion Joyeux Noël is the aftermath.

There's no happy ending. The "higher-ups" were absolutely livid. When the news of the fraternization reached the commanders, they didn't see it as a beautiful moment of humanity. They saw it as treason.

The real-life consequences were brutal:

- Units were broken up and sent to the most dangerous parts of the front.

- Letters home mentioning the truce were censored or destroyed.

- The French government basically pretended it never happened for nearly a century.

Carion shows the German unit being sent to the Eastern Front to fight the Russians. It's a death sentence. The film refuses to let the audience off the hook. It reminds us that while the soldiers found peace, the systems of power demanded war.

The Legacy of the Film Today

If you watch it now, in a world that feels increasingly polarized, it hits even harder.

👉 See also: Blink-182 Mark Hoppus: What Most People Get Wrong About His 2026 Comeback

Carion’s work serves as a massive "what if?" What if the men had just refused to go back? The movie suggests that the war could have ended in 1914 if the people at the bottom had realized they had more in common with each other than with the generals in the chateaus miles behind the lines.

It’s a deeply European film. It was co-produced by France, Germany, and the UK. That collaboration itself is a tribute to how far the continent came after two world wars. It’s why the film was nominated for an Oscar for Best Foreign Language Film. It wasn't just a French story; it was a human one.

Small Details You Might Have Missed

- The Cat: There’s a cat that wanders between the trenches. In real life, the military actually "arrested" a cat for spying because it was crossing the lines. They ended up executing it. Carion included the cat to show the absurdity of war.

- The Wine: The French soldiers sharing their wine with the Germans wasn't just a gesture; it was a huge sacrifice. Rations were terrible. Giving away your alcohol was the ultimate sign of respect.

- The Religion: The scene with the Scottish priest (played by Alex Ferns) giving a sermon to all three sides is based on several accounts of multi-denominational services held in "No Man's Land."

How to Experience This History Today

If you’re moved by Carion’s portrayal, don't just stop at the credits.

You can actually visit the site of the truce. Near the village of Saint-Yvon in Belgium, there is a memorial dedicated to the Christmas Truce. It was unveiled in 2014, 100 years after the event. It’s a quiet, somber place. No big statues of generals. Just a simple marker for the men who decided to be brothers for a night.

You can also look into the actual letters. The book The Truce: The Day the War Stopped by Shirley Seaton and Malcolm Brown is the gold standard for the real-world accounts that Carion used. Reading the original handwriting of these soldiers brings a layer of reality that even a great film can't quite capture.

Actionable Insights for History Buffs

If you want to dive deeper into the world of Christian Carion and the 1914 truces, here is how to do it properly:

- Watch the "Director's Cut" mindset: Focus on the silence. Carion uses sound design to emphasize the transition from the deafening roar of shells to the eerie, beautiful quiet of the truce.

- Verify the Sources: Look up the "Lonsdale Battalion" or the "Saxon 134th Regiment." These were real units involved in the fraternization.

- Explore Carion's Other Work: If you liked his style, check out Farewell (L'affaire Farewell). It’s a different kind of "war" (the Cold War), but it carries that same obsession with the individual caught in the gears of history.

- Visit the Historial de la Grande Guerre: Located in Péronne, France, this museum offers the most nuanced look at the psychological state of the soldiers during 1914.

Joyeux Noël isn't a Christmas movie in the traditional sense. You won't find Santa or magic. What you will find is a reminder that even in the literal trenches of hell, humans are remarkably bad at hating each other once they actually start talking. Christian Carion didn't just make a movie; he gave a voice back to men who were told to be silent for a hundred years.

To truly honor the history, watch the film with subtitles rather than the dubbed version. The struggle of the characters to understand each other through different languages is the heart of the movie. It’s in those moments of "lost in translation" where the real connection happens.

Check out the archives at the Imperial War Museum online. They have digitized several diaries from the 1914 Christmas period that confirm almost every "unbelievable" moment in the film was actually true.