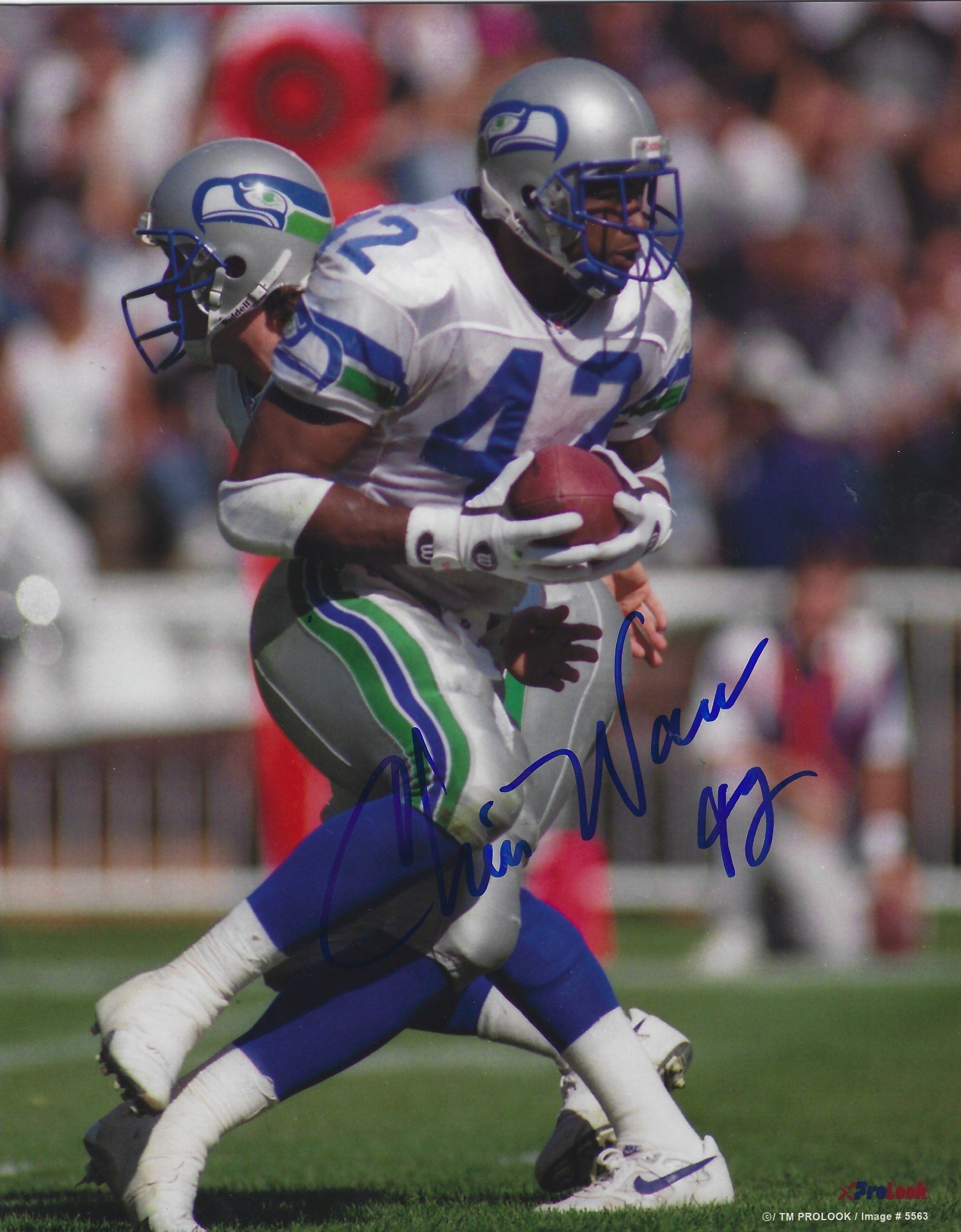

When you talk about the greatest to ever put on a Seattle Seahawks jersey, the names come fast. You hear about Steve Largent’s hands. You hear about the "Beast Quake." You definitely hear about Shaun Alexander’s MVP season where he seemed to score every time he touched the leather. But there is a massive, gaping hole in the collective memory of NFL fans, and it’s shaped exactly like Chris Warren.

Honestly, it's kinda wild how we just gloss over the 90s.

Before the Seahawks were a perennial powerhouse under Pete Carroll, they were a team searching for an identity in the Kingdome. Amidst some truly mediocre seasons, Chris Warren was the engine. He wasn't just a "good" back; for a solid four-year stretch, he was arguably the best runner in the AFC. He was a 6-foot-2, 227-pound gazelle who could outrun cornerbacks and steamroll linebackers.

If you weren’t watching the Chris Warren Seattle Seahawks era in real-time, you missed a guy who broke the franchise rushing record on the very last play of his career in Seattle. And almost nobody noticed.

The Rest Stop Workout That Almost Never Happened

Most NFL stars have these polished origin stories. Warren's started with a broken-down 1986 Volkswagen GTI.

Before the 1990 draft, Warren was a standout at Ferrum College—a tiny Division III school in Virginia. He had transferred there from UVA, and the scouts were skeptical. He was driving to a scheduled workout with the Seahawks when his car died on Highway 81. No cell phone. No GPS. Just a guy at a rest stop payphone thinking his NFL dreams were officially dead.

🔗 Read more: Lawrence County High School Football: Why Friday Nights in Louisa Still Hit Different

But the Seahawks' running backs coach at the time didn't just give up. He drove an hour from the school to find Warren at that rest stop. They didn't go to a fancy facility. They did the workout right there. In the grass. Next to people walking their dogs and truckers stretching their legs. Warren ran routes and showed off that 4.4 speed in a place where most people stop to use the restroom. Seattle saw enough. They took him in the 4th round, and the rest is history.

Why Chris Warren Seattle Seahawks Stats Are Actually Insane

People forget that Warren wasn't the starter immediately. He spent two years as a return specialist, humoring the coaching staff while waiting for his shot. When he finally got the lead role in 1992, he exploded.

Look at the numbers from 1992 to 1995.

- 1992: 1,017 yards

- 1993: 1,072 yards (Pro Bowl)

- 1994: 1,545 yards (led the AFC, 1st Team All-AFC)

- 1995: 1,346 yards and 15 touchdowns

He was the first Seahawk to ever have four consecutive 1,000-yard seasons. In '94, he was basically a one-man offense. The quarterback play was... let's just say "inconsistent." Defenses knew Warren was getting the ball 25 times a game. They stacked eight men in the box. They dared Seattle to throw. Warren still ran through them.

He finished his Seattle career with 6,706 rushing yards. That was a franchise record until Shaun Alexander came along in 2005. Even now, decades later, he’s still #2 on the all-time list, ahead of even Marshawn Lynch. Let that sink in for a second.

💡 You might also like: LA Rams Home Game Schedule: What Most People Get Wrong

The Disrespect of the 1997 Exit

The way it ended was kinda heartbreaking. 1997 was his final year in Seattle. On the very last play of the season, Warren took a handoff and gained just enough yards to pass Curt Warner for the all-time franchise record. He had 6,706. Warner had 6,705.

There was no ceremony. No announcement on the PA system. The fans didn't even know.

The team then went out and signed Ricky Watters to a massive contract, making Warren expendable. He was released and ended up with the Dallas Cowboys. While he was a solid contributor in Dallas—giving Emmitt Smith some much-needed rest—he was never "the guy" again. He was a Seattle legend playing in a blue star, and it just looked wrong.

The Modern Comparison

If you want to explain Warren to a younger fan, think of him as a mix between Derrick Henry’s frame and a more fluid, upright runner like Arian Foster. He had this weirdly smooth gliding style. He didn't look like he was moving fast until he was five yards past the safety.

What Most People Get Wrong About the 90s Seahawks

There’s a narrative that the Seahawks were "bad" in the 90s. They weren't always bad; they were just stuck in the middle. They were 7-9 or 8-8 a lot. Because they weren't winning playoff games, Warren didn't get the national media love that Emmitt Smith or Barry Sanders got.

📖 Related: Kurt Warner Height: What Most People Get Wrong About the QB Legend

But talk to any defender from that era. Ask them who they hated tackling. They'll tell you #35 in the royal blue and silver was a nightmare. He wasn't just a "north-south" runner. He caught 40+ passes a year. He was a three-down back before that was a buzzword.

Keeping the Legacy Alive

Today, Chris Warren is back in Virginia, coaching high school ball and watching his kids follow in his footsteps. His son, Chris Warren III, even made it to the NFL with the Raiders after a big career at Texas.

But if you’re a Seahawks fan, you owe it to yourself to go back and watch the 1994 highlights. Watch the way he moved in the Kingdome. We get so caught up in the modern era that we forget the guys who kept the lights on when things were lean. Warren was the bridge between the early years and the Mike Holmgren era. He was the star when the team had no other stars.

Actionable Insight for Fans:

If you want to truly appreciate Seahawks history beyond the Super Bowl XLVIII ring, start tracking down games from the '92-'95 seasons. Specifically, look for the 1994 game against the Dolphins or the '95 season where he became a touchdown machine. Seeing his usage rate compared to modern "load management" backs will give you a new respect for what it meant to be a workhorse in the 90s.

Check the Ring of Honor. It’s a crime he’s not in it yet. If you're ever in a debate about the best back in Seattle history, don't just stop at Shaun or Marshawn. Bring up the guy who worked out at a rest stop and left as the king of the mountain.