It is just twenty-five measures. That’s it. You can fit the entire score of the Prelude in E Minor Op 28 No 4 on a single sheet of paper if you’re stingy with the margins. Yet, somehow, Frédéric Chopin managed to pack more existential dread and genuine human longing into those two minutes than most composers manage in a four-movement symphony. It’s heavy.

If you’ve ever felt like you’re walking through thick mud at 3:00 AM, you’ve basically lived this piece. There is a reason why it’s a staple for funeral services—including Chopin’s own. It doesn't try to cheer you up. It doesn't offer a "it'll all be okay" resolution. It just sits there with you in the dark.

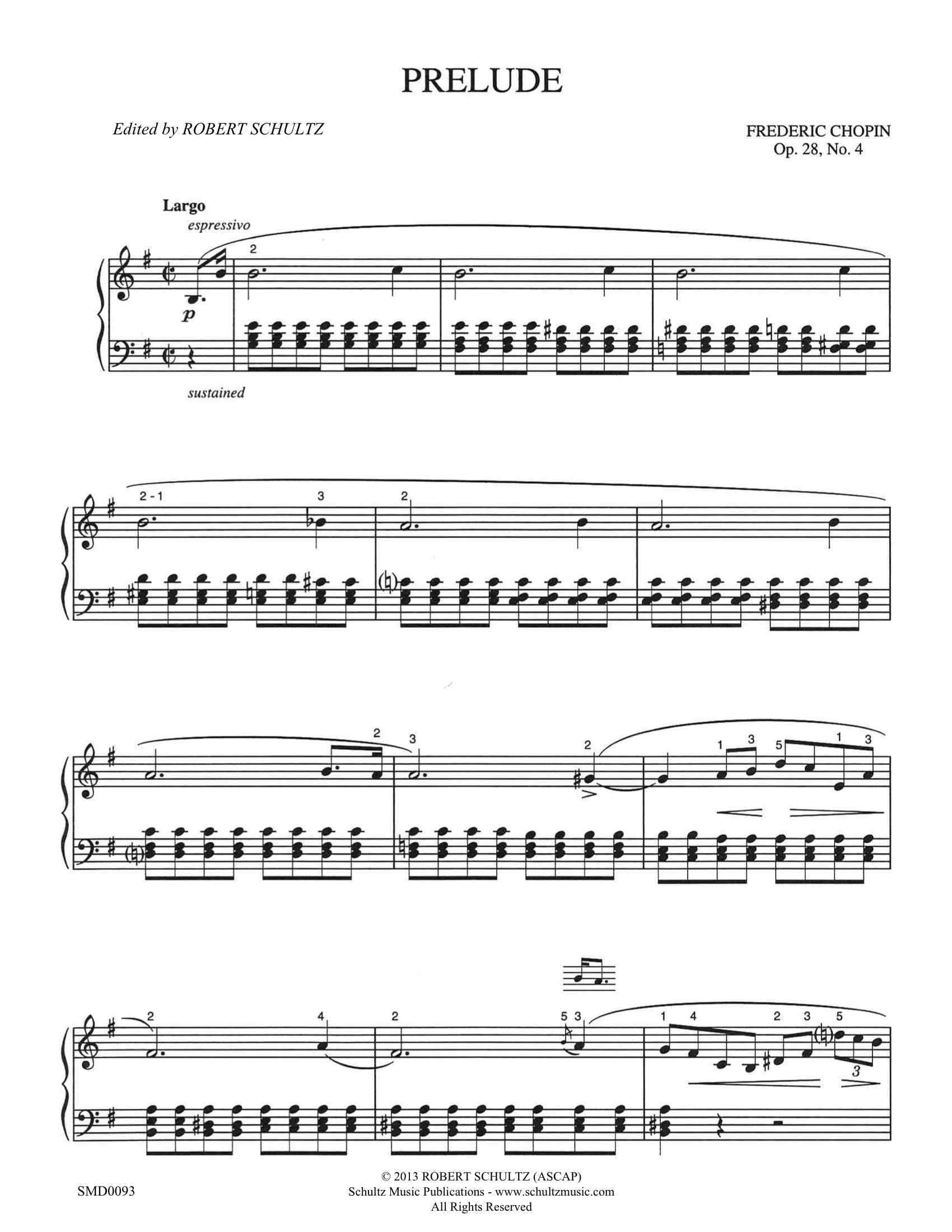

Most people recognize the melody instantly. It’s that weeping, repetitive right-hand line that feels like it’s gasping for air. But the real magic, the actual "how did he do that?" factor, lives in the left hand. Those pulsating chords. They don't just change; they decay.

What’s Actually Happening in the Prelude in E Minor Op 28 No 4?

If you ask a music theorist about the Prelude in E Minor Op 28 No 4, they’ll probably start rambling about chromatic saturation and "stretching the tonal fabric." Honestly? They aren't wrong. Chopin was doing something radical here.

Most music moves from Point A to Point B. You have a chord, it builds tension, it resolves. In this Prelude, Chopin denies you that satisfaction for almost the entire duration. The left hand plays these thick, blocky chords that descend by half-steps. It’s a technique called chromaticism, but here it feels less like a technique and more like a slow-motion slide into a breakdown.

The melody is barely a melody. It’s mostly just the note B, repeated. Over and over. B, C, B, C... it’s obsessive. It sounds like someone trying to speak but losing their train of thought. Because the melody stays so still, the shifting harmonies underneath it feel even more unstable. You’re standing on a tectonic plate that won't stop shifting.

The Mallorca Connection

Context matters. Chopin wrote most of the Op. 28 Preludes while holed up in a cold, damp monastery in Valldemossa, Mallorca, during the winter of 1838–1839. He was there with the novelist George Sand (Amantine Lucile Aurore Dupin) and her children.

✨ Don't miss: Austin & Ally Maddie Ziegler Episode: What Really Happened in Homework & Hidden Talents

It was a disaster.

The locals hated them because they weren't married and didn't go to church. Chopin was coughing up blood—the early stages of the tuberculosis that would eventually kill him. The weather was miserable. He had to wait weeks for his Pleyel piano to be shipped from Paris, and when it finally arrived, he was stuck in a stone room with terrible acoustics.

You can hear the rain. Not literal raindrops—leave that to the "Raindrop" Prelude (No. 15)—but the psychological weight of being trapped in a beautiful place that feels like a prison. Hans von Bülow, the famous conductor and pianist, actually nicknamed this piece "Suffocation." It’s a bit dramatic, sure, but sit down and play those opening chords. "Suffocation" feels pretty accurate.

Why the "Stifled" Melody Works

Usually, a melody is the star of the show. In the Prelude in E Minor Op 28 No 4, the melody is a victim. It’s trapped.

When you listen to a performer like Martha Argerich or Maurizio Pollini play this, notice how they handle the rubato. Rubato is that "robbed time" where a pianist speeds up or slows down for emotional effect. In this piece, if you play it too straight, it sounds like a MIDI file. If you play it with too much "cheese," it loses its dignity.

The difficulty isn't in the fingers. It's in the restraint.

🔗 Read more: Kiss My Eyes and Lay Me to Sleep: The Dark Folklore of a Viral Lullaby

The climax of the piece happens about two-thirds of the way through. There’s a sudden surge. The volume goes up (forte), the rhythm becomes more insistent, and for a fleeting second, it feels like we’re going to break out of the gloom. Then, it just... collapses. The energy vanishes. We’re left with those three final chords.

Those last three chords are some of the most famous in piano literature. They are spaced out. Dead. Silence is just as important as the notes there.

Debunking the Myths: Is it "Easy"?

Beginner piano students love the Prelude in E Minor Op 28 No 4 because the notes are easy to read. You can learn the "map" of the piece in an afternoon. This leads to a massive misconception: that it’s an "easy" piece.

It is arguably one of the hardest pieces in the repertoire to play well.

- Voicing: You have to keep the left-hand chords incredibly quiet and perfectly synchronized, while making the right-hand melody sing out like a tired opera singer.

- The Turn: There’s a little melodic flourish (a turn) near the end. If you play it too fast, it sounds like a bird chirp. Too slow, and it’s clunky. It has to feel like a sigh.

- Pedaling: If you use too much sustain pedal, the chromatic shifts turn into a muddy mess. If you use too little, the piece sounds dry and skeletal.

Famous teachers like Neuhaus or Leschetizky would spend weeks just on the first four measures with their students. It's about touch. It's about how you release the key, not just how you hit it.

The Cultural Shadow of Op 28 No 4

This piece is everywhere. It’s the "Sad Piano Song" trope in movies.

💡 You might also like: Kate Moss Family Guy: What Most People Get Wrong About That Cutaway

- Radiohead: Thom Yorke has cited Chopin as an influence, and you can hear the DNA of this Prelude in songs like "Exit Music (For a Film)." That sense of inevitable downward movement is very Radiohead.

- The Great Gatsby: It’s been used in various adaptations to signal the decay of the American Dream.

- Antonio Carlos Jobim: The bossa nova legend basically lifted the harmonic structure for his song "Insensatez" (How Insensitive). If you play them back-to-back, the resemblance is haunting.

It’s one of those rare pieces of "High Art" that actually crossed over into the collective consciousness of people who don't even like classical music. You don't need a degree in musicology to feel the grief in these notes.

Practical Steps for Mastering the Prelude

If you’re a pianist sitting down with the Prelude in E Minor Op 28 No 4 for the first time, or if you’re a listener trying to appreciate it more, here’s how to approach it without getting overwhelmed.

For the Players

- Ignore the melody first. Seriously. Just play the left-hand chords. Try to make the transition between them as seamless as possible. You’re looking for a "legato" feel without relying entirely on the pedal.

- Practice the "heartbeat." The chords should have a pulsing quality, not a hammering one. Think of it as a physical pulse.

- Watch the dynamic markings. Chopin wrote sotto voce (under the breath). This isn't just "quiet." It's a specific texture. It’s a secret being whispered.

- Record yourself. You’ll think you’re being expressive, but when you listen back, you might realize you’re dragging the tempo. This piece dies if it gets too slow. It needs to keep moving, even if it's a limp.

For the Listeners

- Compare versions. Listen to Vladimir Horowitz for a version that feels electric and nervous. Then listen to Grigory Sokolov for something that feels like an ancient monument.

- Focus on the bass. Instead of following the melody, listen to the very bottom note of the left-hand chords. Notice how it slowly creeps down. That’s where the "horror" lives.

- Use headphones. The subtle changes in Chopin’s pedaling (if the pianist is following his original markings) are hard to catch on cheap speakers.

Final Insights on Chopin’s Vision

Chopin didn't want his Preludes to be seen as "introductions" to other pieces. In his mind, a Prelude was a self-contained emotional state. It was a snapshot.

The Prelude in E Minor Op 28 No 4 is a snapshot of a moment where hope is absent, but dignity remains. It’s not a temper tantrum. It’s a quiet acceptance of loss. When Chopin requested it be played at his funeral at the Church of the Madeleine in Paris, he wasn't being vain. He was choosing the music that best summarized his own struggle with his failing body and his displacement from his Polish homeland.

It’s short because it has to be. You can’t sustain that level of emotional intensity for ten minutes. It would be unbearable. By keeping it to two pages, Chopin ensures that the listener stays right on the edge of the seat, leaning in to catch the last fading vibration of that final E minor chord.

If you want to truly understand the Romantic era, don't look at the giant oil paintings or the 800-page novels. Just look at these twenty-five measures. They tell the whole story.

Next time you hear it, don't just listen for the "sadness." Listen for the craftsmanship. Listen to how he refuses to give you the chord you want until the very last second. That’s not just talent; that’s a deep, intuitive understanding of the human nervous system.

To take your appreciation further, sit down with a high-quality recording—I'd recommend Ivan Moravec for pure tonal beauty—and follow along with the sheet music, even if you don't read music well. Just watch the notes physically descend on the page. It’s a visual representation of a soul sinking, and it’s one of the most honest things ever put to paper.