You’ve heard it. Even if you don't think you have, you definitely have. That lonely, brooding four-note introduction that feels like someone slowly walking through a cold, empty house at 3:00 AM. It’s the Nocturne in C-sharp Minor, Op. Posth. by Frédéric Chopin, and honestly, it’s one of the most misunderstood pieces in the entire classical repertoire.

Most people just call it "the Lento." Some know it as the "Reminiscence." But the truth about this piece is a bit more complicated than a simple title on a Spotify playlist.

Chopin was a perfectionist. Like, a "burn my manuscripts if I die" kind of perfectionist. He specifically asked that his unpublished works be tossed into the fire after his death because he didn't think they were up to his standards. Thankfully, his sister Ludwika and his friend Julian Fontana basically ignored those wishes. If they hadn't, we wouldn't have this Nocturne. It was written in 1830, but the world didn't really get its hands on it until 1870. That’s a forty-year gap where one of the most beautiful melodies ever written just sat in a drawer, gathering dust and risking total erasure.

Why the Nocturne in C-sharp Minor Posthumous Hits So Hard

It isn't just a sad song. It's a psychological landscape.

When you look at the Nocturne in C-sharp Minor Posthumous, you’re looking at a 20-year-old Chopin who was about to leave Poland forever. He didn't know he was leaving for good, but you can hear the homesickness already baking into the notes. Musicologists often point out that this piece was dedicated to Ludwika as a sort of "practice" for his second piano concerto. If you listen closely to the middle section, you can actually hear him quoting themes from the F Minor Concerto. It's like a musical scrapbook.

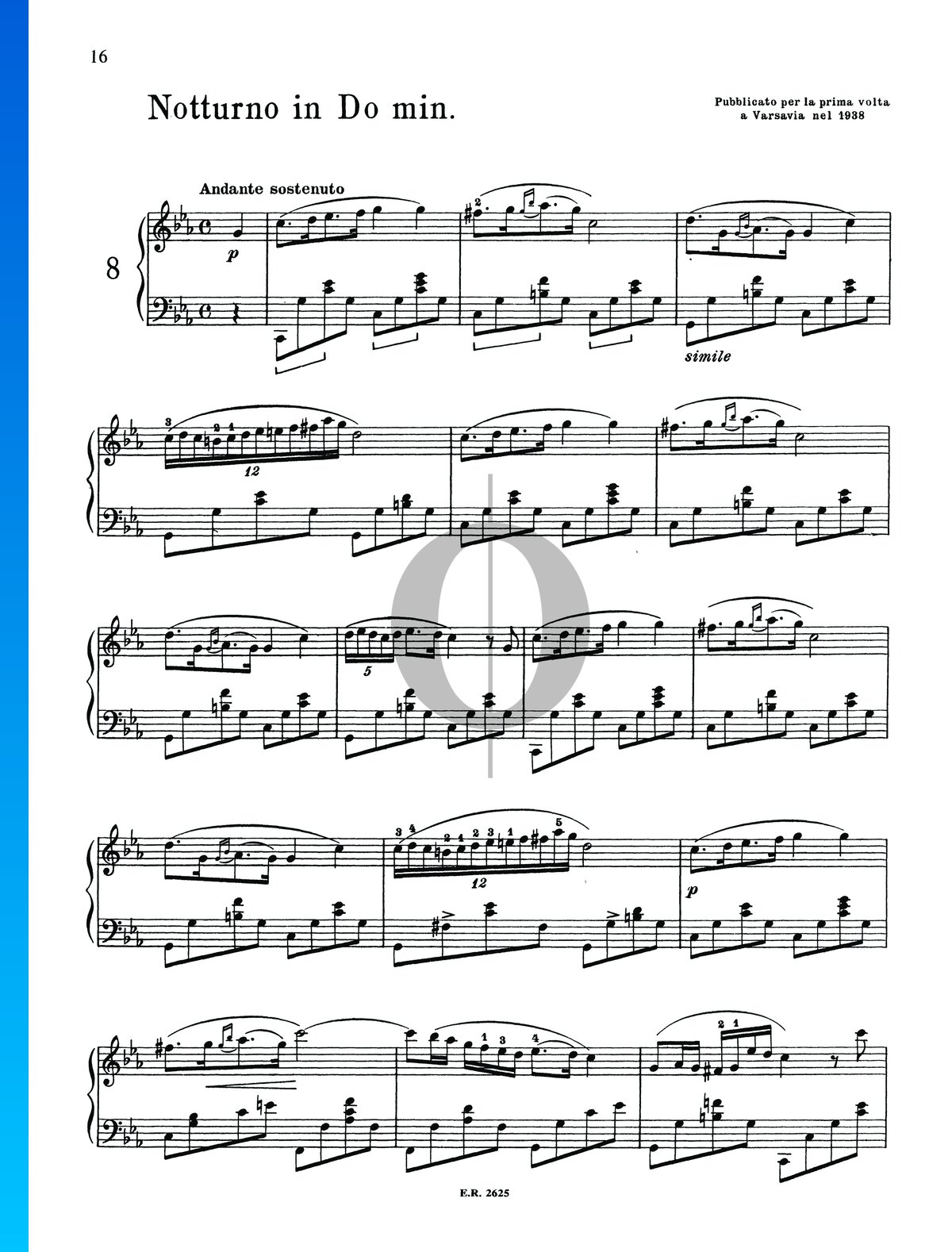

The structure is weird. It’s not your standard A-B-A nocturne. It starts with those heavy, dark chords—the introduction. Then, the melody enters, and it's remarkably simple. It’s a "singing" style, or bel canto, which Chopin obsessed over. He used to tell his students to listen to Italian opera singers to understand how to play the piano. You aren't hitting keys; you're breathing.

The Polyrhythm Nightmare

Ask any intermediate piano student about the "scale at the end." They will probably shudder.

✨ Don't miss: Who was the voice of Yoda? The real story behind the Jedi Master

Right before the piece closes, there’s this ethereal, gossamer-thin run of notes. It’s not a standard scale. It’s a series of tuplets—specifically, 35 notes played against 4 beats, then 11 notes, then 13. It’s meant to sound like a sigh or a gust of wind. If you play it perfectly in time, it sounds robotic and terrible. If you play it too loosely, it falls apart. It requires a specific kind of rubato—that "stolen time" that Chopin pioneered. You steal a little time here, you give it back there. It’s a rhythmic tightrope walk.

The Pianist and the Resurrection of the "Posth"

For a long time, this was just another "minor" Chopin work. Then came Roman Polanski’s 2002 film The Pianist.

The movie tells the true story of Władysław Szpilman, a Jewish-Polish pianist who survived the Holocaust. In the film’s most gut-wrenching scene, Szpilman (played by Adrien Brody) plays this exact nocturne for a German officer, Wilm Hosenfeld, in the ruins of Warsaw.

There’s a reason the directors chose the Nocturne in C-sharp Minor Posthumous instead of a more famous work like the "Raindrop" Prelude. It’s because this piece represents Warsaw. It represents the fragility of culture in the face of absolute destruction. Interestingly, the real Szpilman actually played this piece on the last live broadcast of Polish Radio before the German invasion in 1939. When the station went back on the air six years later, he opened the first broadcast with the same piece.

That isn't just movie trivia. It changed how we perceive the music. It shifted from being a "salon piece" for wealthy Parisians to a symbol of national survival.

What Most People Get Wrong About the "Posthumous" Label

Let’s clear something up. "Op. Posth." isn't a style. It just means the composer was dead when it was published.

🔗 Read more: Not the Nine O'Clock News: Why the Satirical Giant Still Matters

Chopin has a lot of these. But the C-sharp minor Nocturne is unique because it wasn't even intended to be called a "Nocturne." Chopin’s original manuscript actually labeled it Lento con gran espressione. The "Nocturne" title was slapped on later by publishers because, well, nocturnes sell better than "Slow pieces with great expression."

The "Two Versions" Problem

If you go to buy the sheet music, you’ll notice something annoying. There are two versions.

- The "Original" (Ad utum)

- The "Simplified" or "Standard" version

The original version has some very strange rhythmic crossovers. In the middle section, the left hand is playing in 4/4 time while the right hand is playing in 3/4 time. It creates this dizzying, hazy effect. Most modern editions have "corrected" this to make it easier to read, but in doing so, they lose that slightly "off" feeling that Chopin likely intended. If you want to hear it the way it was written, look for the Jan Ekier National Edition. It’s the gold standard for Chopin nerds.

Technical Nuance: How to Actually Play It

If you’re sitting down at a Steinway (or a dusty Casio keyboard) to try this, don't rush the opening. Those first four bars of chords are the "curtain" rising.

The melody needs to be played with what the French call souplesse—suppleness. The biggest mistake people make is playing the left-hand arpeggios too loudly. The left hand is the heartbeat; the right hand is the voice. You don't want the heartbeat to drown out the singer.

Also, watch the trills. Chopin’s trills usually start on the upper note, not the principal note. It’s a small detail that makes a massive difference in whether you sound like a student or a pro.

💡 You might also like: New Movies in Theatre: What Most People Get Wrong About This Month's Picks

And that final C-sharp major chord? It’s a Picardy third. After all that gloom and minor-key wandering, ending on a major chord feels like a tiny, flickering candle in a dark room. It’s hope, but it’s fragile hope.

The Legacy of a "Rejected" Masterpiece

It’s kind of ironic that a piece Chopin basically wanted to delete has become his most streamed work. On platforms like Spotify, it routinely outpaces his "Polonaise in A-flat major" or even his "Nocturne in E-flat major, Op. 9, No. 2."

Maybe it’s because we live in an era of "low-fi beats" and "sad girl autumn." We crave music that validates our melancholy. Chopin’s C-sharp minor Nocturne doesn't try to cheer you up. It sits in the dark with you.

The piece has been sampled by everyone from hip-hop producers to film composers. It’s been transcribed for violin, cello, and even flute. But nothing quite matches the original piano version. The way the hammers hit the strings, the way the sustain pedal blurs the harmonies—it’s a perfect marriage of instrument and emotion.

Actionable Next Steps for Enthusiasts

If you want to move beyond just "listening" and actually understand this piece, here is how to dive deeper:

- Listen to the "Big Three" Interpretations: Start with Arthur Rubinstein for the classic, aristocratic approach. Then, listen to Claudio Arrau for a slower, more tortured version. Finally, find Maria João Pires; her touch is arguably the most sensitive of the modern era.

- Compare the Editions: Go to IMSLP (the International Music Score Library Project) and look at the "Original Manuscript" versus the "Fontana Edition." Seeing the messy crossings of the 3/4 and 4/4 sections will give you a new respect for what Chopin was trying to do.

- Watch Szpilman’s Actual Performance: There are recordings of Władysław Szpilman playing this piece later in his life. It’s bone-chilling. He doesn't play it like a concert pianist; he plays it like someone who is remembering a lost world.

- Practice the "Stolen Time": If you play, try recording yourself. Most people realize they are playing much more "square" than they think. Exaggerate the rubato, then pull it back until it feels like a natural breath.

The Nocturne in C-sharp Minor Posthumous isn't just a piece of music; it's a testament to the idea that some things are too beautiful to be destroyed, even by the person who created them. It survived a fire, a world war, and nearly a century of obscurity. It deserves every bit of the 20 minutes you’ll inevitably spend listening to it on repeat tonight.