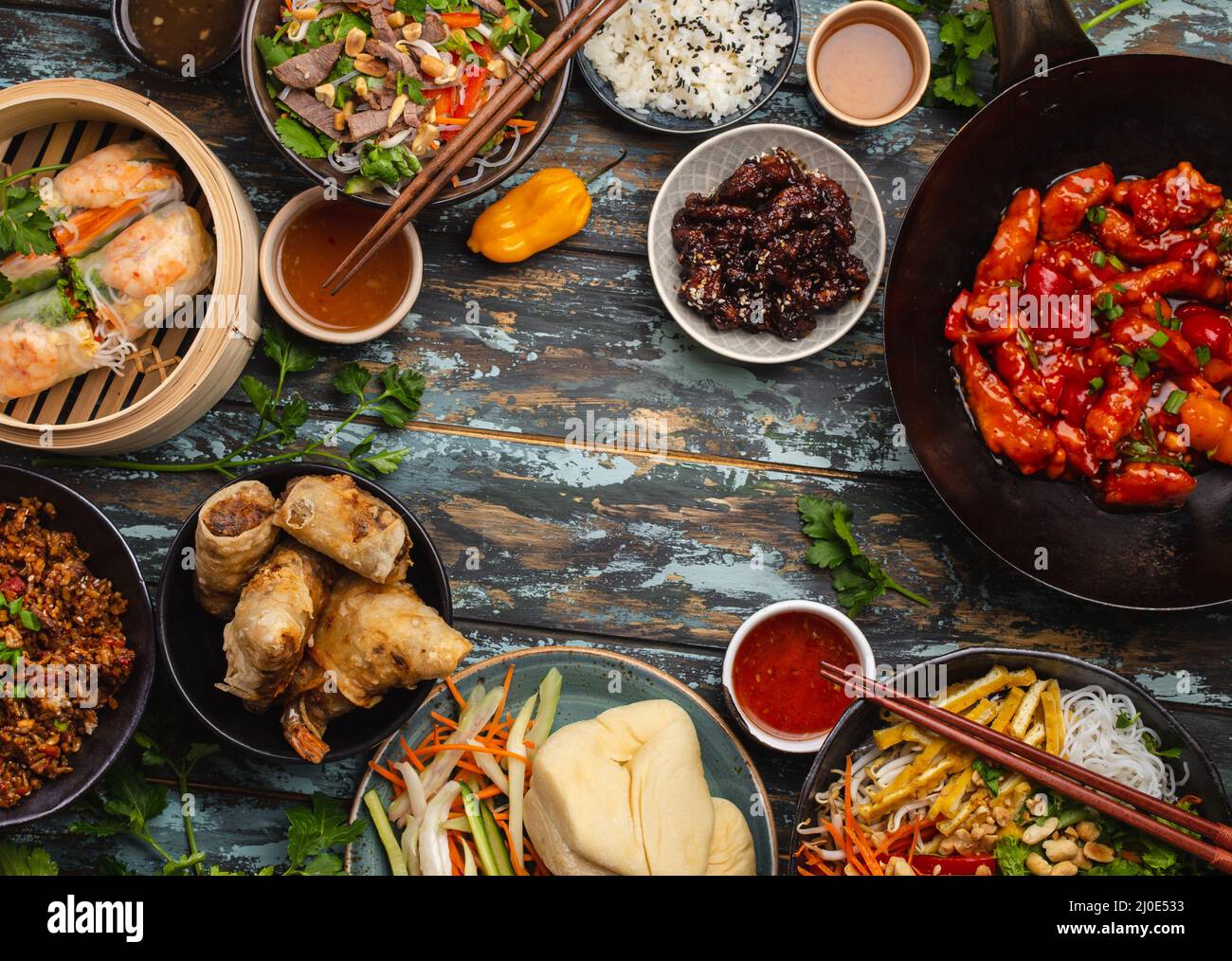

You walk into a suburban Chinese-American spot and see the same fading sun-bleached posters on the wall. General Tso’s. Sweet and sour pork. Broccoli beef. We’ve all seen those chinese dishes with pictures a thousand times. But honestly? Most of those photos don't even scratch the surface of what people are actually eating in Chengdu, Guangzhou, or the bustling night markets of Taipei. China is massive. Like, mind-bogglingly big. Trying to summarize its food in a ten-item menu is like trying to explain European history using only a postcard of the Eiffel Tower. It just doesn't work.

If you’re looking for the real deal, you have to look past the cornstarch-thickened orange sauces. Real Chinese cuisine is about wu wei—the balance of five flavors. It’s about the "breath of the wok" (wok hei).

Why the chinese dishes with pictures you see online are usually wrong

Most stock photos for "Chinese food" are surprisingly inaccurate. You’ll see a bowl of "chow mein" that looks like spaghetti with soy sauce, or "fried rice" that’s basically yellow mush. Authentic Chinese cooking is highly regional. In the North, it's all about wheat—massive, hand-pulled noodles and pillows of steamed buns. Down South in Guangdong? It’s all about the ingredient’s natural sweetness and incredibly delicate dim sum.

Take Lanzhou Lamian. It’s arguably the most famous noodle soup in the world, yet it’s rarely the star of those generic "chinese dishes with pictures" collections. The dough is pulled by hand until it’s thin as hair. The broth is clear, made from beef bones and a secret mix of over 15 spices. If the photo doesn't show a clear broth with white radish slices, red chili oil, and green cilantro, it’s not the real thing. It’s just an imitation.

The spicy numbness of Sichuan (More than just heat)

Sichuan food is having a massive moment globally, but people still get it twisted. It isn't just "hot." It’s mālà. That’s the combination of "mā" (numbing) and "là" (spicy). The numbness comes from the Sichuan peppercorn, which isn't actually a pepper at all—it’s a citrus husk. It vibrates on your tongue at a specific frequency. Scientists have actually measured this; it’s about 40 Hertz. It’s a literal physical sensation, not just a flavor.

Mapo Tofu is the poster child here. When you look at authentic chinese dishes with pictures of Mapo Tofu, you shouldn't see a pale, watery mess. It should be a vibrant, angry red. The tofu should be swimming in a pool of chili oil and fermented broad bean paste (doubanjiang). It’s salty, fatty, and tingling. If there isn't a dusting of freshly ground Sichuan pepper on top, send it back.

📖 Related: Popeyes Louisiana Kitchen Menu: Why You’re Probably Ordering Wrong

The Dim Sum culture you aren't seeing

Go to Hong Kong on a Sunday morning. It’s loud. It’s chaotic. It’s "yum cha"—literally "drinking tea." But the food is the main event. Most people know Har Gow (shrimp dumplings), but they don't realize how hard they are to make. A master chef ensures there are at least 10 pleats on that translucent skin. If it’s doughy or falls apart, it’s a fail.

Then there's Cheung Fun. These are rice noodle rolls. They look like smooth, white sheets folded over shrimp or BBQ pork. They should be doused in a sweet soy sauce. In high-quality chinese dishes with pictures, you can almost see the reflection of the light on the silky surface of the noodle. It should look slippery and delicate, not sticky.

Let's talk about the "Bizarre" factor

Western media loves to focus on the "weird" stuff—insects or chicken feet. But chicken feet, or Feng Zhao, are a genuine delicacy for a reason. They are deep-fried, then braised, then steamed. The result? A texture that is incredibly soft and rich in collagen. It’s not about the "meat"; it’s about the sauce and the skin. It’s a texture game. If you can’t handle texture, you’re missing out on half of Chinese gastronomy.

Regional heavyweights: Beyond the Big Four

Traditionally, we talk about the Four Great Traditions: Lu (Shandong), Chuan (Sichuan), Yue (Cantonese), and Huaiyang. But that’s old school. Nowadays, people are obsessed with Hunan cuisine.

Hunan food (Xiang Cai) is actually hotter than Sichuan food. Why? Because it uses "dry heat"—fresh chilies without the numbing peppercorns to distract you. Duo Jiao Yu Tou (Steamed Fish Head with Chopped Chilies) is the king here. It sounds intimidating, but the cheek meat of the fish is the most tender part you'll ever eat. The picture should show a massive fish head buried under a mountain of bright red, fermented chilies. It’s a visual and sensory overload.

👉 See also: 100 Biggest Cities in the US: Why the Map You Know is Wrong

- Shandong (Lu): Heavy on vinegar and garlic. Think sea cucumbers and braised abalone.

- Fujian (Min): It’s all about the "umami." They use fermented fish sauce and shrimp paste like it's water.

- Zhejiang (Zhe): Milder, fresher. This is where you find West Lake Vinegar Fish. It sounds simple, but the balance of sweet and sour is incredibly hard to hit.

The humble soup dumpling (Xiao Long Bao)

You’ve seen the videos. Someone pokes a dumpling with a chopstick and broth gushes out. This is Xiao Long Bao. Originally from Nanxiang, it’s a feat of engineering. The "soup" is actually a solidified aspic (gelatinous broth) that melts when steamed.

When searching for chinese dishes with pictures of these, look at the top. The "knot" where the dough meets should be thin. If it’s a big hunk of dough, the dumpling will be chewy and unpleasant. A real one has a skin so thin you can almost see the liquid sloshing around inside. It’s a race against time to eat them before they cool down and the skin gets tough.

What most people get wrong about "Healthy" Chinese food

There's this weird myth that Chinese food is inherently oily or full of MSG. First off, MSG is naturally occurring in tomatoes and Parmesan cheese—it’s fine in moderation. Secondly, a huge portion of Chinese home cooking is just "qing dan," or light and clean.

Think of Zhu Di Tou (Lion’s Head Meatballs). In the Huaiyang tradition, these aren't fried. They are gently simmered in a clear broth with cabbage. The meat is chopped by hand, not ground, so it keeps its structure. The result is a meatball so soft you can eat it with a spoon. It’s pure comfort food. It’s what you eat when you’re sick, not a greasy takeout box.

The truth about "Authenticity"

Authenticity is a moving target. Is a dish "fake" because it was invented in San Francisco? Not necessarily. Chop Suey has a fascinating history rooted in the Taishan immigrants of the 1800s. It’s a part of the Chinese diaspora story. But if you want to understand the roots, you have to look at the regional staples.

✨ Don't miss: Cooper City FL Zip Codes: What Moving Here Is Actually Like

Char Siu (BBQ Pork) is a great example. A real picture of Char Siu shouldn't look like it’s been dipped in neon red food coloring. It should have a dark, charred exterior—the "bark"—and a glistening glaze made from maltose, hoisin, and five-spice. The meat should be juicy, not dry.

Actionable steps for your next meal

Stop ordering the same thing. Seriously. The next time you’re at a place that has a "traditional" menu (often written in Chinese on the wall or a separate insert), look for these specific keywords.

- Look for "Shui Zhu": This means "water boiled," but don't be fooled. It’s usually fish or beef submerged in a massive bowl of spicy oil and dried chilies. It’s incredible.

- Identify the "Zi Ran": This is Cumin. Cumin lamb is a staple of Uyghur cuisine in Xinjiang. It tastes more like Middle Eastern BBQ than what you'd expect from "Chinese food."

- Check the Greens: Don't just get "mixed vegetables." Ask for Gai Lan (Chinese broccoli) with oyster sauce or Dou Miao (pea shoots) sautéed with garlic. The freshness will cut through the richness of the meat dishes.

To truly appreciate chinese dishes with pictures, you need to understand that the image is just a gateway. The real magic is in the technique—the way a chef controls a 50,000 BTU burner to sear a piece of ginger in milliseconds. It’s a 5,000-year-old conversation between fire and ingredients. Next time you see a photo of a dish, look at the details: the sheen of the sauce, the cut of the vegetable, the clarity of the broth. That’s where the truth lies.

Avoid the buffet lines. Seek out the regional specialists. Whether it's the vinegar-heavy noodles of Xi'an or the coconut-infused poultry of Hainan, there is an entire continent of flavor waiting behind those pictures. Start with one region and go deep. Your palate will thank you.

Next Steps for the Food Explorer:

- Identify the four major regional styles (Sichuan, Cantonese, Shandong, Huaiyang) on a menu before ordering.

- Search for "authentic" restaurants using regional keywords like "Dongbei" or "Hunan" rather than just "Chinese food."

- Compare the visual presentation of a dish to traditional standards—look for the "bark" on meats and "clarity" in soups.

- Experiment with "mouthfeel" (texture) by trying dishes specifically known for their unique physical sensations, like Q-texture noodles or crunchy wood ear mushrooms.